Nomad architects is a young office focused on sustainability, affordability, and timber construction. The founders of the studio, Marija Katrīna Dambe and Florian Betat, who met while studying in Vienna, work not only on design projects but also teach students and professionals, do research, participate in conferences, host workshops, and talk to policy planners.

Nomad architects do a lot of different things — design, consulting, lobbying, and education. Can you tell me how it all comes together?

Florian Betat:

The core idea for us was to work with sustainability, to do something a bit better for the environment. Our work covers a wide field of different topics and projects of various scales. It might be hard to see the link at first glance, but everything we do is somehow connected to sustainability in architecture.

Marija Katrīna Dambe:

When we say «sustainability», we don’t mean what you find when you search for it on Google images. We are interested in the actual definition of the term and what it means. We try to strike a balance between economics and social and environmental aspects. Being educators is complementary to how we work. Sometimes we teach young architecture students, sometimes we teach construction students who are way older than us and look at things in a really pragmatic way. Being educators creates a feedback loop with the field, and a lot of new ideas come in, helping both sides grow.

Florian:

The theoretical approaches to sustainability have already been established over the last thirty or forty years, but we like to explore and test them ourselves, either by self-building or by experimenting on a small scale before moving on to bigger projects. Whenever we test a new approach, we like to immediately link it to education.

Marija:

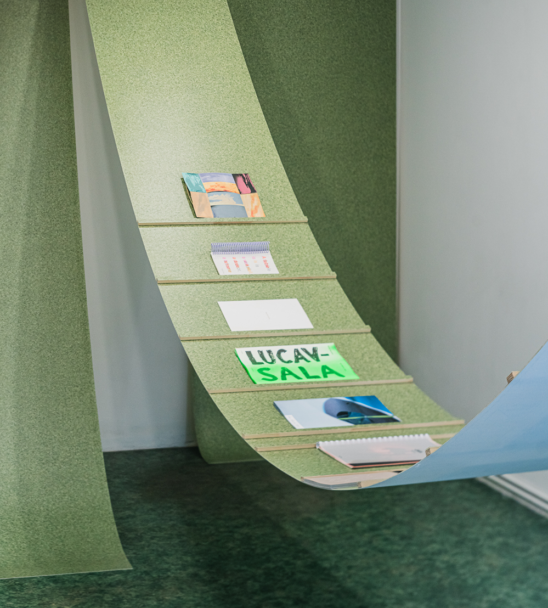

Our educational playground isn’t just theoretical, we like to experiment with different materials or joinery before scaling up. Of course, not every approach scales up — if you can rope-bind construction in a pavilion, you can’t do it in a two-story office building. But then we search for the closest similar principle, evolving the initial idea.

There aren’t a lot of people doing this kind of work in Latvia. How do you feel in this role — a new studio branching out into a field that is a bit neglected?

Florian:

Well, someone has to do it. Since we started, we’ve actually noticed more of a push in the direction of sustainability. More and more people want to go into the field. We also have the benefit of being a small office, and we want to keep it that way because that allows us to be more flexible and experimental.

Marija:

Recently, we’ve seen more and more architects trying to incorporate sustainability into their work. However, this field is extremely lacking in education. If there were a change in the education system, most of the problems we face now would be solved. The new generation of architects and builders could go and help already established offices move towards sustainability. Right now, education on sustainability is a patchwork — there’s a lecture on timber construction here, a lecture on the New European Bauhaus there, but there isn’t a consistent base of knowledge yet.

Was the education you received at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna good in this regard?

Florian:

No, not in terms of sustainability. It was very good in other aspects, though. We got lucky to receive a bachelor’s degree in arts first and then a more technical education at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, where we earned a master’s degree in sustainable architecture.

Marija:

In Vienna, for a whole semester we had a course called Ecology, Sustainability, and Cultural Heritage, where we were encouraged to demolish everything to make space for new ideas. It seemed so illogical and contradictory even back then, when we hadn’t started to think about our part in sustainability. The concept of «cleaning» the city of the old to make something new and supposedly better seemed really strange. There was also this idea that architects just need to come up with a visual concept and somebody else will figure out how to build it. On the one hand, it’s good to not limit yourself as a student to what is practical, but it doesn’t really work that way in reality.

While we’re discussing education, can you tell me more about this new programme at the Vidzeme University of Applied Sciences you are involved in?

Marija:

The New Construction School prepares building construction managers with a focus on sustainability, circular economy, and digitalisation of the construction industry. The old programme was about to be accredited anew. To improve it, the university team started looking into various study topics that needed more in-depth knowledge: timber construction, waste flows, building acoustics, and user comfort. We also offer workshops, bootcamps, and summer schools, as well as internships, partnerships with building companies, and collaborations with educators and students in Estonia and Finland. At the university, we are trying to incorporate online learning and new ways of approaching youth while keeping in mind what the construction field actually expects from new graduates.

How is this new content landing with the students?

Marija:

It’s a bit too soon to say, but we’ve had a strong start last year. For example, we had a student who was working with foam insulation for the whole year. Learning about the environmental and circularity impacts of the material, using the knowledge from the programme, and observing construction processes on site, he realised how bad the foam insulation actually is. He ended up changing it all up at the last moment. What this shows is that the students start to notice and pay attention to these things themselves. It is one thing when someone just tells you how things should be done, but quite another when you see the impacts of these decisions in practice. For example, when designing for disassembly, it’s not just a theoretically good thing; it’s very practical for the builders. When you make a mistake, you can fix it and patch it up easily. It saves you all this time, money, and materials well before the lifespan of the building comes to an end. When students start to see these benefits on a real construction site, they don’t need to be convinced to build sustainably, it just makes sense.

Florian:

We recently had an intensive workshop together with Romanian students at the university, where an existing building on campus needed to be reused for a new facility. We started by analysing what materials the building is made of, what can be salvaged and repurposed on site, and what can be recycled. The students were quite in shock because this approach is so different from what they are used to — first come up with a volume and then think of the practicalities. That’s how architecture is mostly taught — first make it pretty and then figure out how to build it. It was very nice to see how even one intense week of workshops had already managed to change their understanding of how buildings can be designed.

What’s your relationship with aesthetics in your practice — do you let the practicalities dictate the visual outcome?

Florian:

We are searching for an aesthetic in every project, but it always needs to come from functionality. If it’s not functional, we don’t see it as beautiful. There always needs to be some sort of justification for a certain element, some logical reasoning for placing a certain object somewhere. You can see this approach in traditional buildings a lot. Take, for instance, the ornamental facade overhangs with a zig-zag shape often used in traditional wooden architecture. It not only looks good but also helps to get rid of rainwater and prolongs the lifespan of the material.

We also tend to prioritise a very clear floor plan — a clear grid with the least amount of elements and repeated dimensions translates into a certain architectural language. I’d say our aesthetic is more of an emergent property.

Marija:

We also try to build for disassembly by using open connections and not hiding what the building is made of — that also creates a certain honest aesthetic. One of the first tasks we give to any student — either architecture or construction students — is to give them random Archdaily pictures of recent buildings and ask them to list how they would take that building apart. They quickly learn that things are mostly hidden to create a certain look, but that’s not actually necessary. There’s room for a lot of play in working as an architect within practical restrictions and interacting with the city around the building.

When I hear discussions about sustainability or circularity, or accessibility I can’t help but see the wider political context within which these discussions take place. How do you deal with this broader ideological context that surrounds your work?

Marija:

Well, environmentalism is always perceived as a left-wing ideology right from the get-go. Although we all live on the same planet, breathe the same air, and drink the same water, caring for the environment is somehow a political issue. It’s absurd, because conservation of the environment should actually be sort of a conservative topic, but in this political climate, it’s regarded as something very left-wing.

Florian:

It comes down to what you want to conserve — is it the way you are used to burning oil and coal or is it conserving the climate?

Marija:

Seeing sustainability or human-oriented buildings as a left-wing topic is such a shame because it affects us all and should be our common basis. Cities have to be built for people, no matter what their political leanings are.

You can follow Nomad architects on their website and Instagram account.

Viedokļi