At the beginning of September, the 6th Tallinn Architecture Biennale (TAB) dedicated to the theme Eating; Or, The Architecture of Metabolism was opened. Here, the relationship between the built environment, eating, and digestion is examined both in a literal and figurative sense, focusing on urban agriculture and circular architectural practices.

«Edible aims to empower architects, planners, and environmental designers to develop a proactive stance on architecture’s expressive capacity to perform circular operations, to produce resources — generate food and energy — as well as to decompose itself,» says Lydia Kallipoliti and Areti Markopoulou, curators of this year’s Tallinn Architecture Biennale.

Both curators are Greek architects whose interests include sustainable urban environments, technologies, as well as experiments with new materials. Kallipoliti, who has worked at a number of prestigious architectural education and research institutions and has received several awards for her work, focuses specifically on theories of reuse and self-sustaining systems. Markopoulou, on the other hand, aims to redefine architecture through the synthesis of technology and design. She has led and founded several research institutions, as well as taken part in the development of Barcelona’s urban planning guidelines.

The problems that have shaken the world in recent years — the Covid-19 pandemic, social inequality, climate change, Russia’s war in Ukraine, and the energy crisis — have highlighted the fragility of the usual order, including our food systems. Overpopulation and the ever-growing appetite of humanity which goes with it, means that it is critical to find new ways to produce, consume, and not waste food.

The curators speak unflatteringly about our current consumption habits: «We ingest the planet, and the planet in turn becomes the repository for our secretions.» They invite us to look at architecture and the built environment as a self-sufficient organism that not only consumes, but also creates and regenerates resources. At TAB, the vision of «living» architecture was presented in the curatorial exhibition, symposium, catalogue, vision contest, and school exhibitions, as well as in the pavilion of the installation programme.

Living machine

The central exhibit of the curatorial exhibition is Metabolic Home, which connects metabolic processes with our lifestyle and spaces, offering to replace Le Corbusier’s «machine for living» with a «living machine». Each of the rooms in the house interacts with different aspects of eating or digestion — from food production in the vertical garden to waste processing in the garage.

At the exhibition, attention is drawn to the kitchen created by architect Andrés Jaque (Office for Political Innovation). Made from marble blocks left over from stone quarries, it looks prehistoric and futuristic at the same time. Various functional recesses have been carved in the blocks, allowing microorganisms to become our culinary companions and blurring the lines between cooking, eating, and decomposing. The spectrum of rituals related to eating is also expanded in the exhibition dining room, where architects Hayley Eber and Mae-Ling Lokko have laid a bountiful table that becomes a tool for growing, cooking, and processing food, thereby reducing our alienation from these processes.

Although generally the message of Metabolic Home is clear, individual ideas are expressed on different conceptual scales, which makes them more difficult to understand. For example, the lounge is based on the concept of architectural research group Terreform One. They propose facade panels that would be regularly eaten by animals and insects, thus promoting the diversity of nature in the built environment. In the exhibition, this material is used as a cover for furniture, making its function unclear. What is eaten is also excreted, so the exhibition also draws attention to how much drinking water we waste by flushing it down the toilet. The bathroom of the Metabolic Home, created by Ecological Action Lab, conceptually becomes a water treatment system consisting of a fountain and a pool built from plastic bottles. Although visually impressive, the installation obscures its own message by including too many different elements, but none that speak about the process of treatment itself.

Pragmatic utopia

It should be noted that a critical view of some of the exhibits can be perceived rather as a compliment. Bringing up crucial, but currently rather theoretical topics such as circular architecture and the future of cities, the works of architects often tend to be deeply conceptual, but the curators of TAB have tried to introduce these themes in a more practical context. «We don’t want to create utopias, but offer solutions. That’s why we invited start-ups to participate in the exhibition along with architects and designers,» said Lydia Kallipoliti at the opening of the curatorial exhibition.

Most of the exhibited solutions are not market-ready products, but they allow the vision of a more sustainable future to be brought closer to reality. In the Metabolic Home, the garden is brought to life in a system that has robots taking care of the harvest, developed by the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia. Currently, vertical gardens are expensive to maintain and require highly skilled workers, but robotic gardeners could solve this problem. An interesting and localised solution for vertical gardens is offered by the Estonian architecture studio Part, who have developed a prefabricated facade system proposal Datša Wrap, which combines small gardens and fire escape, cleverly interpreting the Tallinn building regulations, that allow the construction of metre-deep bay windows.

Estonia is also represented at the biennale by the start-up Myceen, which uses mycelium to «grow» various interior elements and acoustic panels. In this process, the mycelium «eats» wood industry waste and grows, taking the form of a mould. Mushrooms have been invoked as an agent of change in architecture for some time, and Myceen is currently developing a thermal insulation material that would be a carbon-negative alternative to stone wool. In the From Brick to Soil section of the curatorial exhibition, you can see a partition wall made of mycelium blocks and a few blocks that are still growing. Looking at the wall, you involuntarily want to touch and smell it, which the curators encourage you to do.

From the cornucopia

Wood industry waste is also used as a resource by the German start-up Made of Air, which turns it into carbon-negative materials. In the garage of Metabolic Home, visitors can see bricks made of sugar and Made of Air biochar. But the true value of this material was revealed to me at the TAB symposium, where the founder of the company, Allison Dring, talked about the cooperation with such recognisable brands as Audi and H&M. As emission limitations increase, companies are interested in improving their carbon balance sheets with the aid of carbon–negative materials.

Usually, sustainable practices are associated with abstinence and giving up something. But the fact that in the future we might be able to monetise these practices by selling their value to those who cannot or do not want to live greener offers a new perspective and opportunities. Maybe we don’t need a comprehensive change in thinking at all? Maybe the cult of consumption just needs to be turned in a different direction.

Kallipoliti and Markopoulou also emphasise the need to look at sustainability issues through a «mindset of abundance». In the From Brick to Soil section of the exhibition, various options for increasing the variety of resources available to us are explored. For example, the architects of Studio Aine have conducted an experiment in which they looked for ways to turn gypsum leftovers and waste from the water treatment system into materials. Furthermore, the design research studio Topotheque calls for interspecies cooperation by building artificial coral reefs and thereby renewing fish populations.

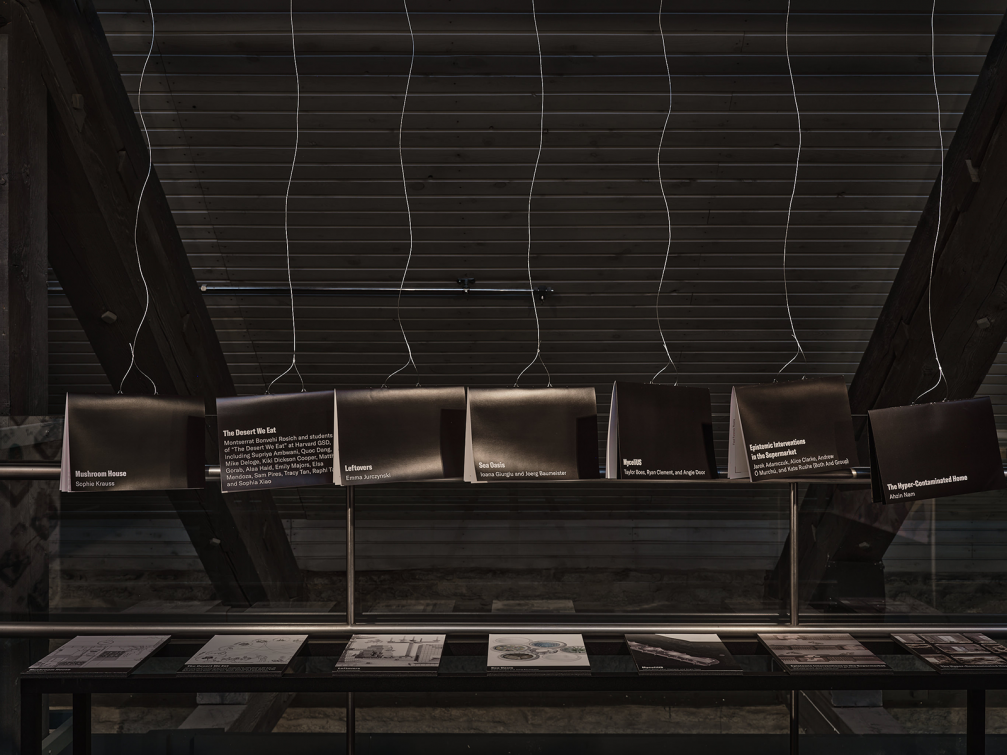

Admittedly, abundance is not always what is needed. The Future Food Deal section of the curatorial exhibition gathers both proposals from prominent architects and researchers, as well as ideas submitted in an open call, which address both food systems and the metabolic capabilities of architecture. There are so many proposals and they are so diverse — from gourmet Tinder to food synthesis systems in cities — that it is difficult to grasp the huge amount of information.

All around the table

It is clear that in the face of climate change, overpopulation, and resource scarcity, our habits will have to change, and these changes must be global. The Food and Geopolitics section of the curatorial exhibition focuses on proposals that have been developed on a large scale. For example, the Black Almanac platform created by researcher Philip Maughan and visual engineer Andrea Provenzano offers 31 steps to implement a sustainable global food system by 2050. At TAB, Black Almanac is presented as two short films, which, based on the cultural aspects of food, speculate on ways to satisfy humanity’s growing need for food. The Tallinn 1.5 project by the urban research practice SPIN Unit is also interesting. It explores the possibilities of growing all the food needed by the population of Tallinn and proposes food labels that would reveal the ecological footprint of the product.

An idea that could globally change the design and construction process is offered by the winning proposal of this year’s installation competition. Fungible Non Fungible created by the mixed reality design studio iheartblob is the first blockchain pavilion in the world. Anyone interested can mint a part of the pavilion, keeping its digital version in their possession, while financing its physical construction. This idea would theoretically allow architects to implement their ideas with crowdfunding, as well as give the opportunity for architecture to develop organically and according to the wishes of society. However, the pavilion also highlighted the unpredictability of this idea. The physical pavilion in front of the Estonian Museum of Architecture underwhelmed with its modest size. As it turns out, it can be blamed not only on the inertia of the public, but also on the desire of the budding designers to create small parts. I hope that during TAB, Fungible Non Fungible will continue to grow to fully reveal the potential of this idea.

The topic of community building was also addressed in the TAB vision contest, which focused on the largest Soviet microrayon in Tallinn, Lasnamäe, where about a quarter of the city’s population lives. The participants of the competition had to propose solutions for the neighbourhood, which would allow it to become more sustainable and produce its own resources, while, at the same time, strengthening the community. The proposal envisages gradually demolishing the existing buildings and using their materials together with the timber from the forest to rebuild the district on a human scale. Moreover, to do it at a speed determined by the regrowth of the trees. In my opinion, the proposal Super Neighbour, which got second place, stood out among the competition entries. Based on the same mechanisms that make us hungry for likes and hearts on social networks, the authors of the idea propose an app where neighbours can collect points by doing good deeds and making sustainable decisions in order to gain more influence over microrayon’s built environment.

In conclusion, TAB offers a wonderful platform to meet architects and researchers from all over the world to participate in discussions about the future of architecture not only during the symposium, but also at other events. Furthermore, the curators of the biennale were happy to talk to anyone and explain their vision. It is said that every family should come together at the table, and for those interested in a different — more circular and living — architecture, TAB opens up an opportunity to symbolically do so.

Tallinn Architecture Biennale continues until November 20.

Viedokļi