The world-famous and enigmatic American architect, theorist and educator John Hejduk turned to Riga for the first time in 1987, when the installation Object–Subject was displayed at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. It was later accompanied by a book The Riga Project, which documented Hejduk’s structures. Now, 35 years later, RISEBA Faculty of Architecture and Design and the organisation Arhiteksti are reanimating this project with a new, enriched edition and a promise to build the installation in Latvia.

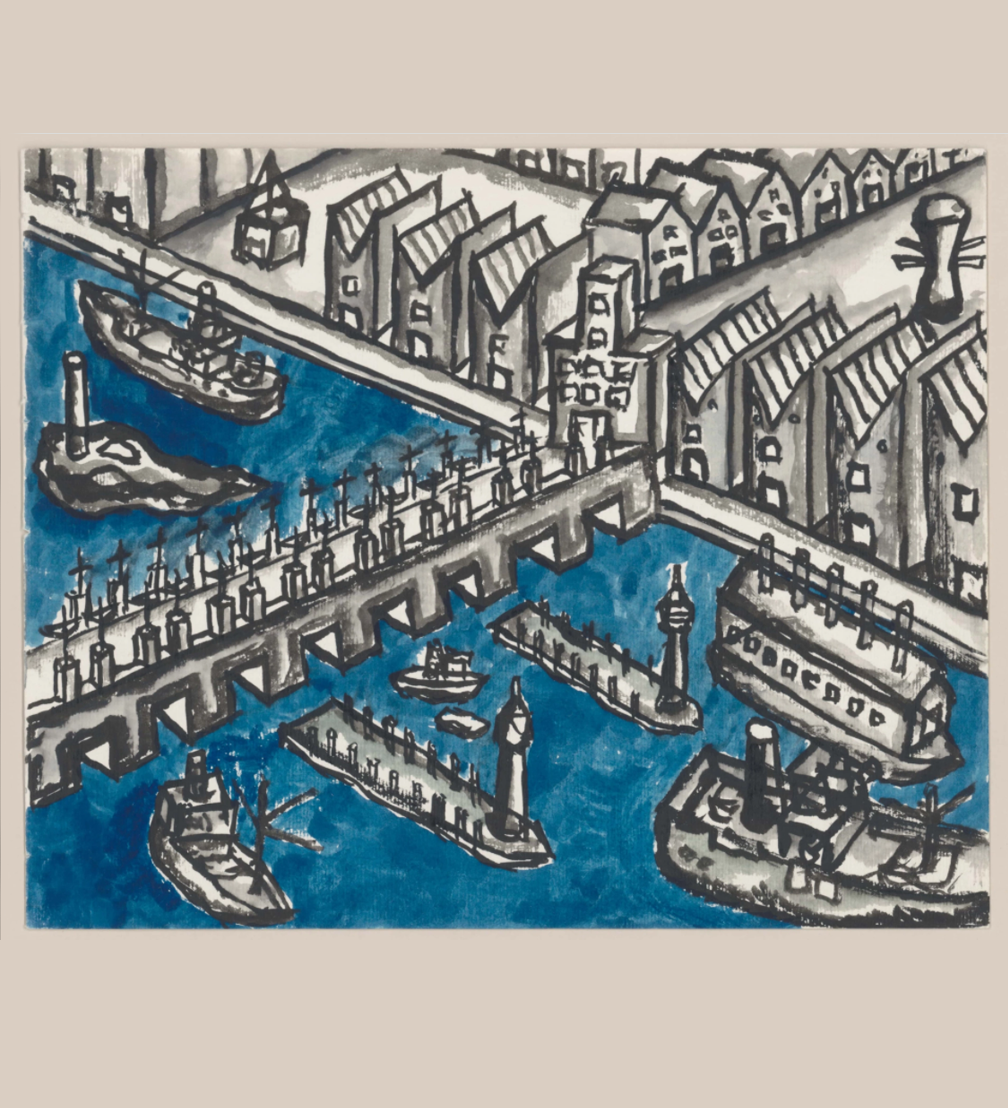

Hejduk’s fellow student, colleague and co-author of the original Riga Project Larry I. Mitnick recalls leading the Summer Academy of Fine Arts in Salzburg together with Hejduk as a time when the idea to work on The Riga Project was born: «Each day we rose early and walked along the River Salzach, crossing the Mozartsteg to the Festung Hohensalzburg. We spoke of remote things: Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest, the Holocaust, Mozart, Berlin, Goethe, Tanglewood, the paradox in Germanic culture, Rilke, narrative, marionettes, nutcrackers, clocks, funicular penetration.» When thinking of The Riga Project, this quote dawned on me several times because it embodies the scope of Hejduk’s thought. In his speculative architecture he abandons the conventional frame of the profession and turns to war, ideology, myth, humanity’s collective psyche and abstract form. Hejduk’s sketches and drawings, which are the main product of his artistic activity, are rooted in a wide range of fundamental themes, that are connected by an unnamed, sometimes obscure, but always present thread.

It appears this approach has been taken up by the authors of the book Second Act: The Riga Project, the organisation Arhiteksti. This volume complements the original and now translated 1989 publication The Riga Project. Between its covers are both poems by Kārlis Vērdiņš and Efe Duyan, paintings by the architect Rudolfs Dainis Šmits, references to Japanese cyberpunk comics and definitions from the Merriam-Webster dictionary, as well as drawings by the architect Malgorzata Maria Olchowska, excerpts from the Hejduk-inspired online exhibition by artists Elza Sīle and Indriķis Ģelzis, an essay on Palladio, and a search for new locations for Hejduk’s Riga structures. The contributions of architecture students stand out in particular ― both the aluminium sculptures by Sergey Kopil as well as the speculative architecture in the Daugava Concert Hall project by Gustavs Grasis and Kirill Khusid contain direct references to Hejduk’s method and explore the relationship between objects and subjects. Apparently, John Hejduk’s pedagogical approach has found fertile ground at the RISEBA Faculty of Architecture and Design thanks to its new dean, Rudolfs Dainis Šmits, who is also among the authors of the book. Although the usefulness of Hejduk’s approach in architectural practice remains contested among his researchers, it certainly has a place in the academia, particularly in the Latvian architectural education, which has for many years been absent of conceptual thought.

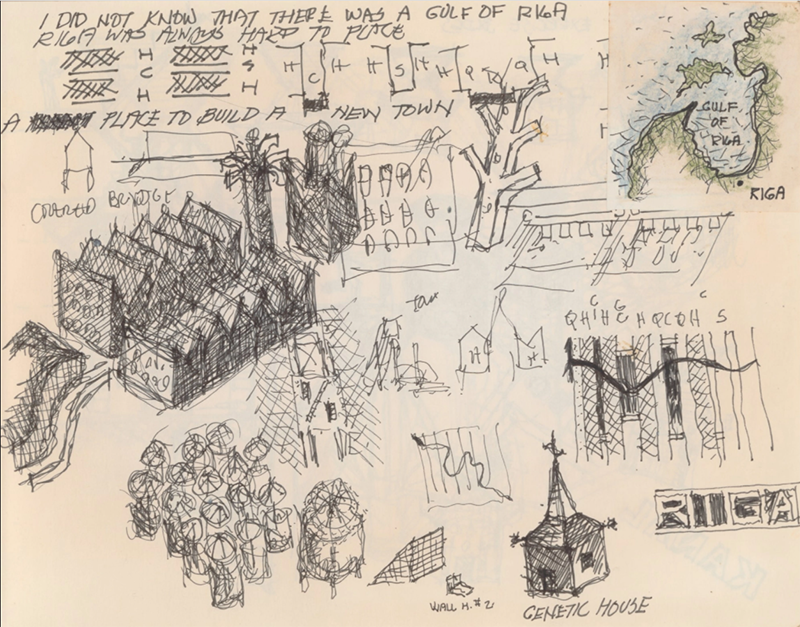

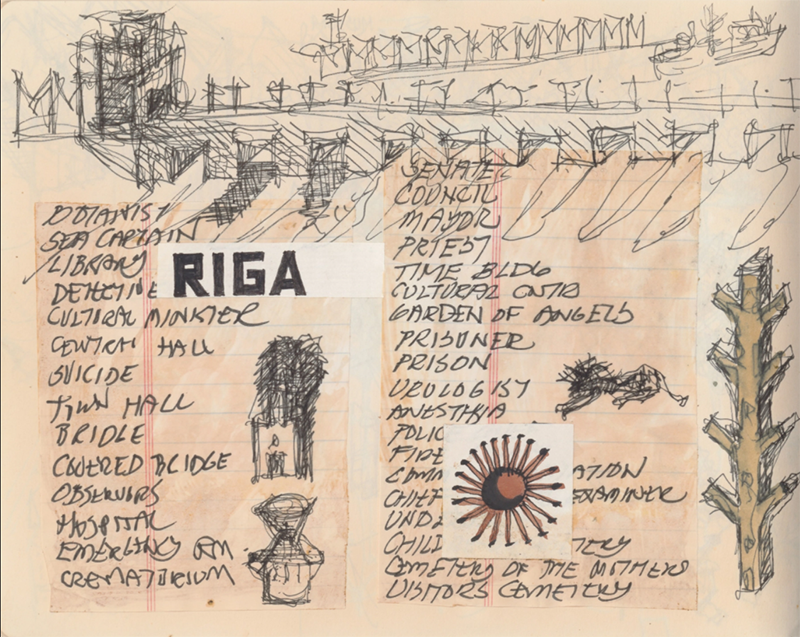

What does The Riga Project have to do with Riga? Essentially — almost nothing. The Riga Project is part of Hejduk’s so-called Russian trilogy about Riga, Lake Baikal, and Vladivostok. Even if Hejduk has ever visited Riga (thoughts on this are divided, although we can be almost sure that he has not been in Vladivostok or Baikal), it is not evident. What’s more, he deliberately mystifies Riga: «I did not know that there was a gulf of Riga. Riga was always hard to place. A place to build a new town.»[i] In a 1989 interview with the writer David Shapiro, Hejduk recounts an episode from the opening of the Riga installation in the USA: «A woman came up to me in Philadelphia who was pretty outraged. She said to me that she lived in Riga, and the Riga I present was not the Riga she knew. She was really very angry and not nice to me. I said, «Your Riga is your Riga, and my Riga is my Riga…»» Hejduk’s Riga is a distant, not entirely real, slightly exotic city somewhere behind the Iron Curtain. It earned the attention of Hejduk because it is near to a site of Holocaust. The Russian trilogy is a continuation of Hejduk’s metaphysical journey from the West to the East, during which he created several dozen objects of speculative architecture. While the objects devoted to the Western cities of this route ― Venice and Berlin ― seem to be more rooted in the real histories of these cities, the Riga installation Object-Subject could easily be located in any other Eastern European city. This is due to the fact that Hejduk operates on two scales: one is a micro-scale, focusing on the individual and the local relationships between, say, a candle-maker and his house; the other is a cosmic, universal scale, exploring civilisation as a whole, focusing on big life-death cycles, on time and space.[ii] The medium scale at the level of society, city and local history is rarely found in Hejduk’s works.

In the volume Second Act: The Riga Project one of the proposed locations for the installation Object-Subject is the bridge for the once-planned railway line between Tukums and Kuldīga, also known as the bridge to nowhere. On a micro-scale level, it is an appropriate and poetic environment for Hejduk’s structures, but on the macro-scale the ideal location for them is Eastern Europe as a bridge between the East and the West. Hejduk has often been criticised for his apolitical stance and avoidance of the real life. Although he places his architectural objects and subjects within existing cities (often the same ones in different cities) without regard for the local, historical, and political context of these places, he is very political on the macro-scale. The horrors of the Second World War and pessimism regarding the future of civilisation constitute a large part of his work and personal mythology.[iii] While preparing to build the Object-Subject in Latvia, Arhiteksti have so far refrained from political overtones, but in view of today’s geopolitical context, Hejduk’s works are more current than ever before.

Hejduk’s sketches, drawings, and speculative architecture lend themselves to a variety of interpretations — scholars have theorised on his idiosyncratic mythological world, the theatricalisation of the collective memory, references to both situationism and modernism, as well as medieval crafts and spiritualist practices. The same wide range of interpretations is also offered by the book Second Act: The Riga Project. And to some degree that’s Hejduk’s intention — he’s been interested in the relationship between image and text, architecture and thought all his life. But his scepticism regarding language must also be remembered. In a 1994 interview with architectural critic David Cohn, Hejduk has said: «Language is drowning out architecture. Architects are trying to obfuscate language. Words, words, they’re throwing them out. And it’s all so thin. There’s no thickness in it.» After all, the real protagonist of Hejduk’s artistic output is image and architecture, not text. The best way to experience Hejduk’s unique, unusual, and timeless architecture is to stand opposite his anthropomorphic sculptures and let them speak for themselves. And very soon that will be possible here in Riga and elsewhere in Latvia.

[i] From the foreword of John hejduk’s book Valdivostok Riga Lake Baikal

[ii] Catherine Ingraham writes about it in her essay Errand, detour, and the wilderness urbanism of John Hejduk

[iii] In the same essay Catherine Ingraham highlights Hejduk’s fascination with danger: «The militaristic danger of spikes and points; the surgical danger of knives and pain; the psychological danger of identity, snakes, and suicide; the spectator’s danger of freezing up at the spectacle (Medusa); the theological danger of crucifixion and falling.»

Viedokļi