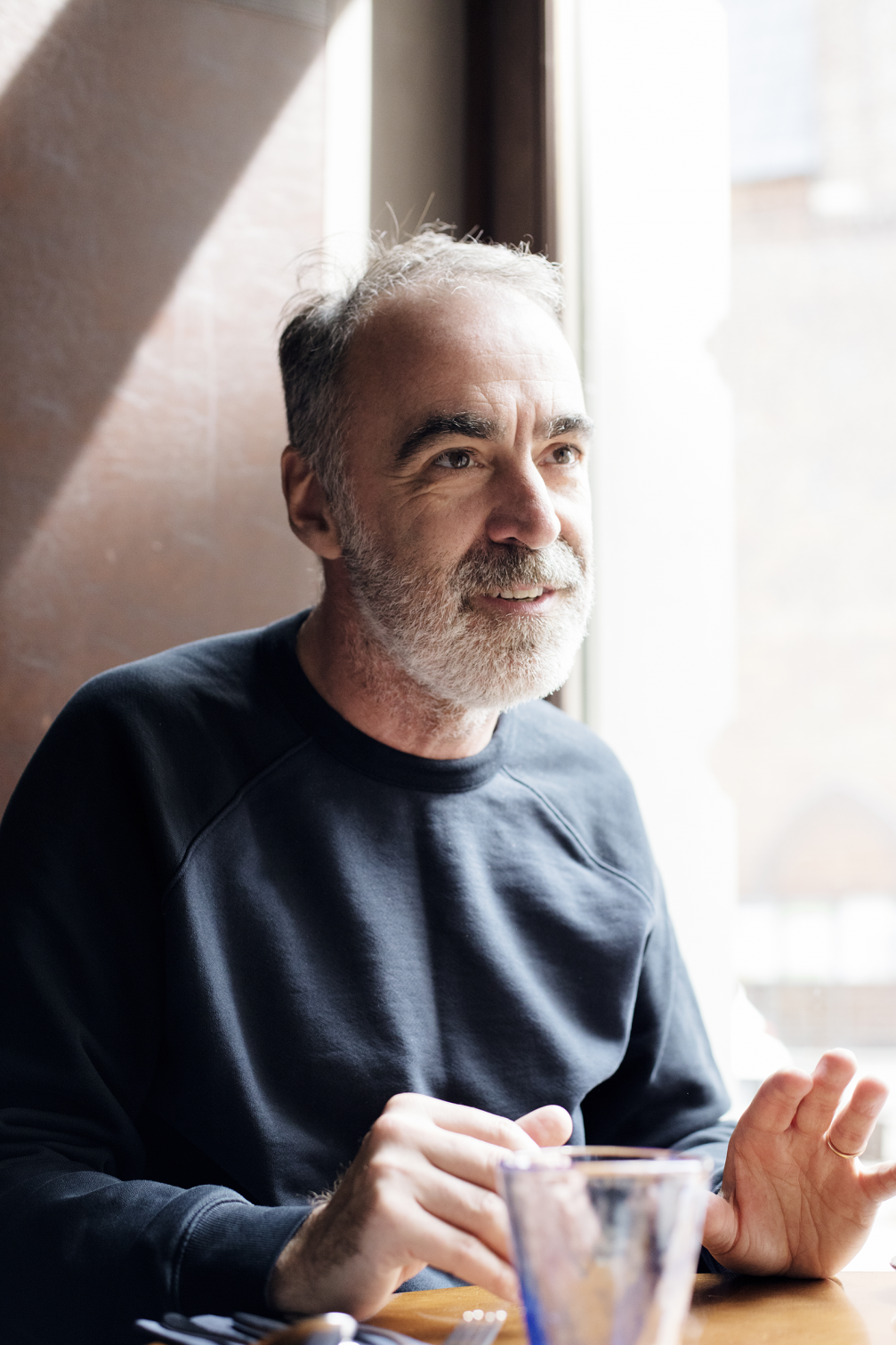

David Cook is an architect who has worked for the renowned architecture studio «Behnisch Architekten» for nearly twenty years. In 2012 he founded his own office «haascookzemmrich Studio 2050» together with his colleagues Martin Haas and Stephan Zemmrich. Working closely together with the climate engineering office «Transsolar» David looks for sustainable, energy efficient and environmentally friendly solutions in architecture. «Studio 2050» are the authors of the concert hall «Latvija» and Ventspils music school.

How did you become interested in sustainable architecture?

Initially I went to an art school to study architecture. So, to an extent, I could define my own curriculum. When I studied in Manchester I was very interested in Glenn Murcutt’s work and his declaration to «Touch This Earth Lightly». When I moved to Germany, I tried to apply thermodynamic principles to buildings, looking at how air moves through them and how this influences the process of design. I was introduced to «Transsolar» while carrying out concept design work for a large public building in Lübeck, and I have worked very closely with them on every single project since then.

I do, however, deliberately separate a progressive energy concept from sustainable design. Sustainability is a huge subject, it’s communal, societal. It’s essentially about our way of life. For me, it is relatively easy to pursue a progressive energy concept, but to pursue a progressive sustainable design agenda is a challenge. This is one of the primary aims of our office. By calling ourselves «Studio 2050», we try to face the issues yet to come. We recognise that our capacity is limited, so our studio is set up in a way that encourages dialogue with consultants and experts from different fields. We don’t see our engineers as people who merely fulfil the basic requirements, taking the architectural drawings and putting their systems on top of them. For us design is very much a coordinated, collaborative effort. And that is the most enjoyable part of any project, of being an architect — looking for those synergies between design, environment, structure, light.

What role has teaching had in your career as an architect?

In 2012, I was a visiting professor at the University of Oregon. Since I couldn’t reconcile teaching a program about sustainable architecture and flying back and forth every week, I stayed on the campus for four months, which was a fantastic experience. The contact with students is incredibly interesting. The educational environment offers a testbed for ideas, it is rewarding to see how the students respond to the impulses you give. They can explore an environmentally progressive design process without the constraints of working in an office. Creativity is less restricted. Then, some years later, I see how some of the ideas generated through that dialogue with students come back into the office when the time is right.

I’ve been to Oregon a few times since and I have taught in various other places, but never full-time. Although rewarding, it is very time consuming and to marry the demands of teaching and the demands of a new office is nearly impossible.

You won the competition for the concert hall «Latvija» back in 2005 together with your colleague Martin Haas, but the project came to a halt after the financial crash. How has the initial design and program changed?

It is quite unusual to establish the surrounding landscape and public square prior to the building. Normally you’d finish the building and the landscaping would come a summer or even a year later. I think that, had we done it the other way around, we would have run into financial constraints at the end of the project, and the landscaping would have been inevitably effected, or even postponed. The financial crisis worked out to our advantage here, and the mature trees really add to the experience of going to a concert.

When the client received the backing of the European Union, the program changed quite dramatically with greater importance being placed upon the integration of the music school in the building. The project became much richer. What’s difficult for an outsider to understand is the role music has in Latvian culture. Once the music school became part of the project, it gained much more momentum. Our intention from the very beginning was to make music more accessible to the public through the form of the building. The fact that the concert hall is on the Big Square helps a great deal, the building serves as a beacon, pulling people in, encouraging them to be curious and to partake. Now it’s down to programming. I hope they can ensure that the performance spaces are used day in, day out, which is something that doesn’t happen with a concert hall that stands alone. Here, there is a natural synergy between the individual parts of the building.

In addition, the music school functions as both an acoustic and thermal buffer to the main hall. Our progressive energy concept became even stronger with the cellular spaces providing an outer layer protecting the building core. During a normal project, aspects of such a progressive energy concept might be up for debate, but in this particular case the client never wavered, because the energy concept was crucial to the EU funding.

Can you describe the energy strategy of the project?

Whenever we start a building of this scale, we attempt to reduce the future demands placed on the city. We don’t want to produce something with huge energy consumption that places financial burdens on the client on a yearly basis. We therefore adopted a series of interrelated moves. Firstly, we have a high performance, highly insulated thermal envelope. A tight envelope raises the question of where to get fresh air. We introduced five earth channels underneath the building and the landscape that allow us to naturally ventilate the building, including the main hall, which is very rare. The earth channels pre-heat or pre-cool outside air depending on the season. If the air is not the right temperature or humidity, it is diverted to the mechanical plant, which is much smaller than it would be without the earth channels. We also draw on the foundation system with water circulated through the piling; the concrete slabs radiate warmth or cool, tempering the indoor environment. We have an innovative ventilation system for the classrooms. They are individually served by decentralised units which breathe air in and out through the façade with a built-in energy recovery unit. The biggest advantage is that there is little ductwork, which in turn reduces noise in acoustically sensitive spaces.

The progressive energy concept is defined by numerous moves working together to produce a far-reaching impact on the appearance, organisation and operation of the building. It works hand in hand with the acoustic concept. Such an energy strategy would be considered highly ambitious even in Germany. I hope that the user can operate the building in the correct manner. This will take a bit of time — to learn how to work all the systems.

How would you describe your collaboration with your Latvian colleagues, the client and others involved in the project?

I’m very grateful for my Latvian colleagues who helped us with anything that came up. It is a challenge to work in a foreign country. It was, for example, quite difficult to find a Latvian heating and ventilation expert who could implement the «Transsolar» energy concept. Without forging close relationships with your colleagues such a project would not be possible. I was fortunate that we had young Latvian architects in the office at that time who helped us with the language barrier.

The client was very supportive and proactive. The trust they gave me was impressive. My office is relatively young, we’ve got 30 people, but when we started the project we were only 8. Being an architect you propose certain design solutions, and you’re not sure if you’ll be taken seriously, if the client is willing to go that far. Here in Ventspils instead of saying «we can’t do that» the client’s attitude was rather «show us how can we do that».

We were, however, given only 9 months to prepare the technical project, including accommodating the programmatic changes. Looking back, that was extreme. I don’t think anybody should try and do a concert hall in less than a year and a half, but there were certain funding requirements that needed the designs to be completed at a certain point in time. We tried and did as much as we could. There are parts of the project that I would like to have been given more time to develop further. There are some details that are not yet finished, and I hope those small things will be corrected. But overall I’m very happy with the result.

Are you an optimist when it comes to our sustainability efforts and the future of climate change?

I think it comes down to fully understanding the challenges posed by striving for sustainability. It is a collective responsibility. We need a consensus on a political level, but the problem is that politicians don’t have the power they had 50 years ago, they are basically the play-things of big industry. People have been thinking about electric cars for over a century, but certain industries do what they can to stop these efforts. There are so many issues where true leadership is demanded, but you need the top-down and the bottom-up grass-roots movements working hand in hand. Governments and big industry have been manipulating opinions for many years, and only now we are starting to see how the public can use social media to their own advantage. Take, for example, Fridays for Future. Besides, you don’t want just anybody standing there and telling that story, you want a 16-year-old school girl from Sweden representing tomorrow’s planet. I am an optimist. I think that things are going to change dramatically, because of people like her.

In some ways, your architecture practice and work in implementing progressive energy concepts is at the forefront of our response to climate change.

No, I don’t think so. My work has minimal impact. Who reads about round-earth constructions or earth channels, or micro ventilation systems? I agree that every drop in the ocean counts, but major advances can be made by the Swedish schoolgirl. I can stand in front of an architecture conference and talk about a building, but we should be talking on the scale of a city. We should not be developing buildings as individual elements, but instead exploiting the synergies within a city. I’m a realist when it comes to how much you can do with a single building.

Still, you can do a lot more than just design an expressive piece of architecture. I wish more was expected from a building in terms of performance and environmental footprint. I hope that the Ventspils Concert Hall shows that it is not just a showpiece, because it was not about making a visual landmark. Of course, you don’t often build a concert hall in a small town of less than 40,000. Any town that comes upon 26 million euros wants to show off to an extent, and that makes sense. But it is the job of any architect to work with and lead the client, and I’d like to see more collective responsibility and less excessive consumerism in society as a whole. That change has to happen not only on a national level, but on the level of the Baltics, the European Union, and further.

Do you think the «Latvija» concert hall responds to some of these larger sustainability issues on the scale of the city?

In a sense, the concert hall addresses the brain drain to the capital. The unspoilt Latvian countryside is amazing — going from the airport to Ventspils is like driving through a national park; but the countryside is shrinking, and unfortunately it doesn’t support a great deal. Efforts have to be made to slow the young generation from moving to Riga as a stepping stone and then moving away to Amsterdam or Paris. That is critical for the long term health, vibrancy and sustainability of a city. Boosting the local competition between Ventspils, Liepāja, Cēsis, Rēzekne is also important. That’s where the issues of sustainability come in on a societal level. This is why I think that building a new concert hall in Ventspils was a wise decision. Twenty-six million well spent.

Viedokļi