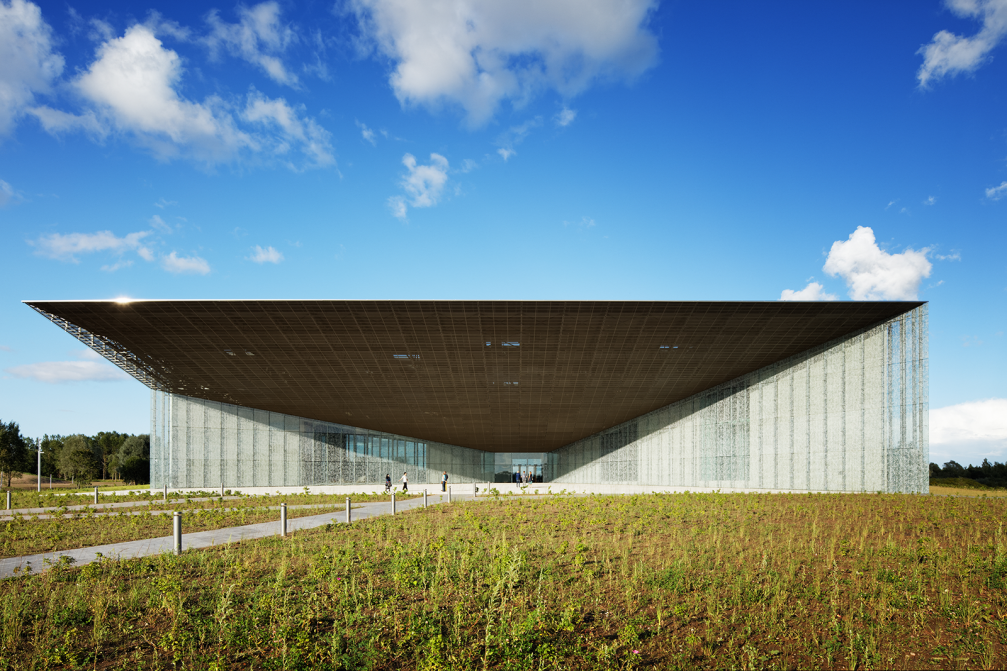

The Estonian National Museum in Tartu opened its doors on October 1, 2016, ten years after three young architects Dan Dorell, Lina Ghotmeh, and Tsuyoshi Tane entered the international architectural competition with a concept entitled Memory Field. The name suits the museum well — the elongated glass volume blends with the bare landscape of the former military airfield, embodying a peaceful monumentality. Winning the competition served as the occasion to establish Dorell Ghotmeh Tane Architects (DGT) in 2006, and the museum project has become a defining feature of the practice.

Lina Ghotmeh, one of the founding partners of DGT, was born in Beirut, Lebanon. Architecture studies at the American University of Beirut and Ecole Spéciale d’Architecture in Paris provided Lina with a dual cultural background. Before setting up her office, she worked with Ateliers Jean Nouvel in Paris and Foster and Partners in London. Lina has always been interested in archaeology, which has influenced the research–driven design approach of her practice. She has received numerous awards for her work, the most recent ones being AFEX Grand Prix 2016 for the Estonian National Museum project and the Prix Dejean by the French Academy of Architecture.

How does your interest in archaeology reflect in the research you do for each new project?

Each project is a quest, an opportunity to confront new questions. For example, what is a national museum in the 21st century in Estonia? What does constructing a residential building in Beirut mean today? How to produce new meanings or new relationships with the architecture I am creating? All these questions arise and become research issues for the act of intervening in a certain context. Of course, architects have an intuition, a feeling in the beginning — what to do and how to intervene, but it starts to become more substantiated once you dig into the context and the traces of history.

For the Estonian National Museum project I dug into the history of Estonia. The project questioned the competition brief, it goes beyond the assigned site and links to the military airfield. The trace of what was once a painful history is now appropriated into the museum realm; the runway becomes a continuation of the museum roof, a new public platform. The building starts to act on the territorial scale, as an urban generator of the area.

Do you have a heightened sensitivity for the local context?

I always feel there is a genius loci awaiting to be revealed in each site I have to work with. But it’s not just about sensitivity, it is also about knowledge. I always distinguish between knowledge and information: information is accumulation of data, while knowledge is in–depth analysis of interconnected information. Knowledge needs time, it is a historical construct.

Was it possible to predict that the museum project was going to resonate so widely in Estonia?

When we were designing the project, of course, we debated — how to deal with things that might be a taboo in Estonia? We had to go beyond the established notions of memory and history. We had to propose that and not be afraid of what the reactions could be. To face an opposition, it was interesting. It is part of architecture. If everything is neutral, perfect and nice, it means you’re not creating new meanings. New meanings always generate discussions.

Ten years ago, Estonian newspapers questioned the relevance of this building’s architecture. The museum design was an opportunity to talk about the history, the present, the future of Estonia. Estonians adhered to our vision for the project, and it resonates very positively in the country today. I was so touched to be thanked by Estonians walking on the street during the Museum’s opening week. These moments are the best compensation for architects.

Projects of that significance often polarise opinions. How do you deal with criticism, can you ever be prepared for it?

For me, it is important not to develop a defensive attitude. It is about really explaining the reasons behind something, trying to bring people to adhere to this new vision. It has to be part of our mission as architects — to connect to the public. It is true that architects tend to be alienating sometimes, it is an elitist culture. There is a discrepancy between what we make and how the public conceives it. But we should remember that architects design just about 20%, maybe even less of the built environment.

You have said that you had to defend the public space in the Estonian National Museum project. Is that something you see as part of your role as an architect — to advocate for public space?

It’s quite overwhelming to have so many roles, but at the same time I feel it is within our responsibility. We are situated at the crossroads of disciplines, we are able to see certain dynamics and to redefine them through the built environment. It is something I discovered through the profession — as an architect you can’t just design and build nice buildings; you are also a citizen with an awakened sense of responsibility to defend and a capacity to create meaningful spaces. Not in the sense of saving the world, but creating new situations, articulating relationships in space. I thrive to design each project, regardless of its function, as a public space.

You have designed several spaces without a predefined function for the museum. Is it easy for an architect to give up that control and leave it to the users to fill the spaces with programme?

The materials and the dimensions of these spaces are defined. The only undefined thing is the function, the program. The large entrance canopy, the reception area, the bridge, the runway — these are the places where the unforeseen can happen. These are spaces for serendipity, for happiness; they connect people. I think these spaces are essential for a public building, and this goes beyond the functional or aesthetic quality. This makes me think of the situationist theory — about creating unforeseen situations, event spaces. It also relates to the perception of architecture as an event, as Bernard Tschumi may have put it. It’s about understanding that as architects we don’t control all situations. The most captivating spaces in cities usually are those that are situated between what is purposely built. From this perspective, the museum acts as a city.

Your office often takes part in competitions. What is the competition brief that fascinates you?

It becomes interesting for us when the brief goes beyond just architectural programme, when there is ambition. The brief for the Estonian National Museum was very interesting — it had historical, ethnographical, ecological dimensions. It described the museum as a place for constant memory work, a landscape of memories. It had both a poetic and sociological dimension — that allowed us to rethink the building.

In another competition I lead and won in Paris, Réinventer Paris, the brief was as compelling. The site of the project and the ambition for innovation were the only frame for the proposals. The competition invited architects to assemble multidisciplinary teams to propose not only an architecture but also a program, a contemporary way of living, a sustainable design that is able to respond to the city’s current challenges. The building I designed, Re–alimenter Masséna, deals with climatic change through its architecture and on the micro scale — the program is articulated around a sustainable food chain. It is a wooden building, and it is going to be built in 2019.

Was the developer also part of your Réinventer Paris competition team?

Yes, and that is when it became a feasible utopia, one that had economic feasibility as well. All aspects were studied to make the project real. It’s a completely reversed approach to a competition — normally in the brief you have the programme, then you submit your proposal, and then the fight starts. But here you had to begin with finding the client and developing the programme together. The jury evaluated the architecture, the programme, the innovation, economic viability, environmental impact. There were more than 800 proposals, and it took a whole year to select the winners.

The Re–alimenter Masséna residential tower is almost an educational machine. Is that something you aim to achieve — to create architecture that educates people, makes their lifestyles healthier?

It is interesting to think about how architecture can create a sustainable relationship between people, and people and Earth. When you live there, the act of living becomes an act of learning. In a usual apartment building or a hotel everything is compartmentalised, but here you can really be part of the cycle. You understand something about food, planting, cropping, recycling, and not just get your banana or mango from the other side of the world. It’s a lively place that allows you to be aware of all the cycles of living, it supports a circular economy, forbids excessive wasting and consumerism.

A substantial part of your work is exhibition spaces — showrooms, galleries, museums. Is that an interest of yours — to tell somebody else’s story?

Architecture is about orchestrating new stories, ones that can live in different time spans. The architecture of an exhibition design or a dance performance creates an experience for a few days or months; the story of a building is much longer. I like the idea of staging realities in different temporalities, from the ephemeral to the permanent. I am also interested in architecture as a spectacle where the visitor becomes an actor in the space, it is a theatrical way of relating to spaces.

What are the most important traits of an architect?

Ambition. Dream. Curiosity. Perseverance. Critical thinking. Empathy.

Viedokļi