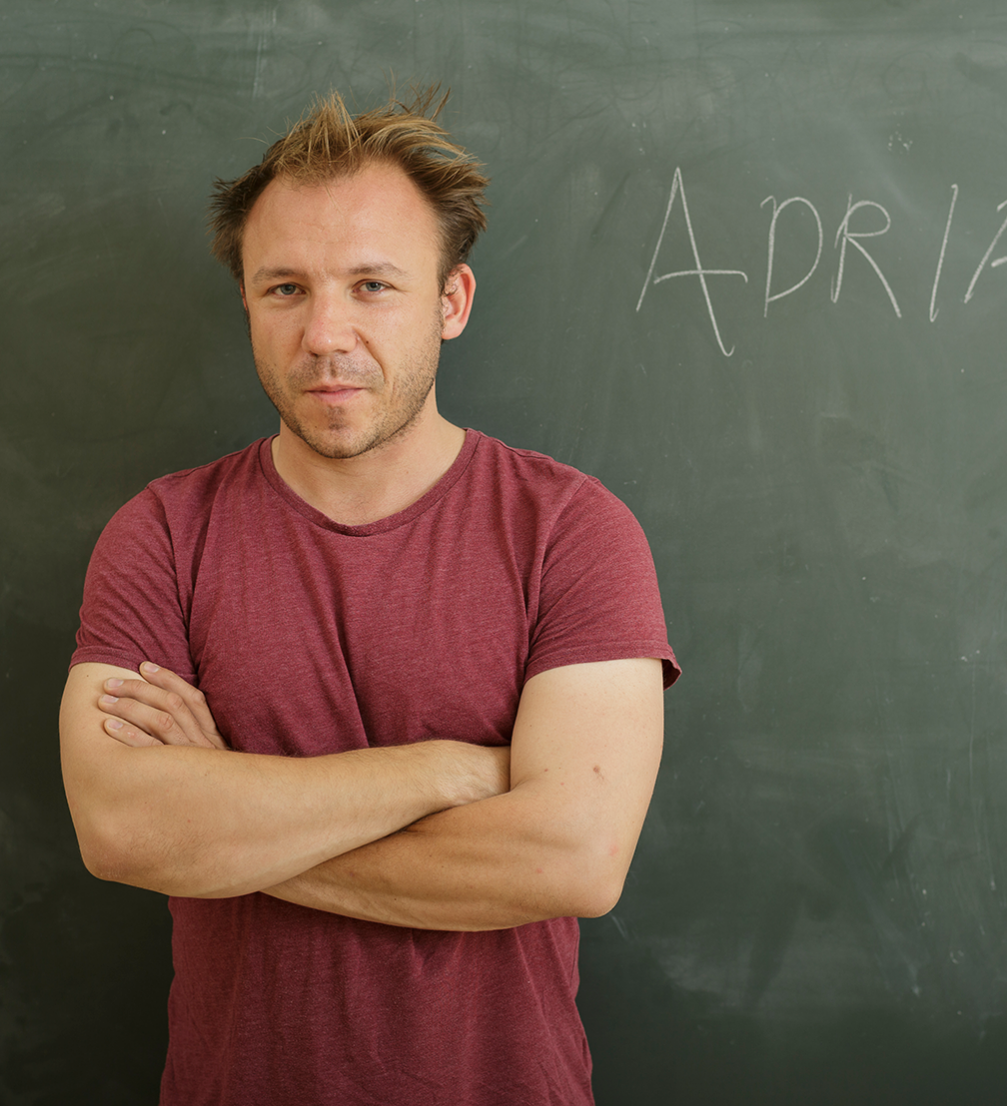

Adrian Kelterborn, an independent film director and multimedia producer, has lead the Magnum Photos multimedia studio Magnum in Motion in New York, creating over 100 multimedia essays closely with the world’s best photographers, and worked together with such influential organisations as The New York Times, The Global Fund, Leica, Médecins du Monde and others. For some time now Adrian has returned from overseas to Switzerland — a culture he feels rooted in, to develop his own visual language and work on projects that fuse various media, storytelling forms and spaces.

You connect photography with the cinematic media, creating multimedia photo stories. What attracts you to such format?

Photographers often have great access to certain stories; they can dig in deeper and work on a project longer, because they don’t need as many resources as a full scope film team, so it’s really interesting in terms of content. Also technically, I’m keen on this experimentation of how these two mediums could melt together. This broadness of visual approaches and views represented by different media is what’s exciting today.

What does your job as a multimedia producer entail?

There is a lot of confusion of what «multimedia producer» means. Often there is a lot of management involved in terms of who do you connect, but it can also entail finding funding, initiating projects and performing as a director. There are a lot of photographers with an incredible visual sense, but they lack audio skills, and a lot of incredible musicians with an amazing sense for sounds, but not so much for the visuals. Your job as a multimedia producer is to marry those too.

Can a person do it all or is it crucial to involve other professionals?

When working with multimedia, you get to the end of your own skills very quickly. You can produce a small solid story, collect the pictures, sounds and videos and pull it off on a high level, but it takes a lot of time, and then you might need a motion, graphic or sound designer. I see multimedia placed in the middle, attached to different fields and specialists.

What subjects are at the focus of your field of interest right now?

There are three levels of stories that interest me — local, as I’m based in Switzerland, European, and global. Currently I’m working on a project with Liza Faktor from the visual storytelling production studio Screen and the photographer Michael Christopher Brown who covered Libya during the revolution. The project is called «Libyan Sugar», and it’s interesting that we actually have a book dummy as a start, but also a ton of videos Michael shot with an iPhone while he was in Libya. So we are trying to translate his story into a filmic form which could maybe also turn into an installation later on. For every project I ponder on how it would look as a movie, as an interactive piece with data or a book, map out different visual answers for that subject. Ideally, you create a package that really works together, and the mediums supplement one another. It’s important to know on which level you’re working, who’s interested in the story and how to curate that to the audience.

Have some of your projects resulted in an emotional impact on yourself?

We did a really great project with Magnum called «Access to Life» for The Global Fund that wanted to show how AIDS is treated globally in different countries, and how the family and society view these people, because there is also a social and cultural level attached to the medical treatment. Photographers were sent to 9 different countries to portray the situation that would result in an exhibition, a book and a multimedia piece. It was fantastic to work on that scale, seeing how every medium contributes to others in creation of the strongest impact.

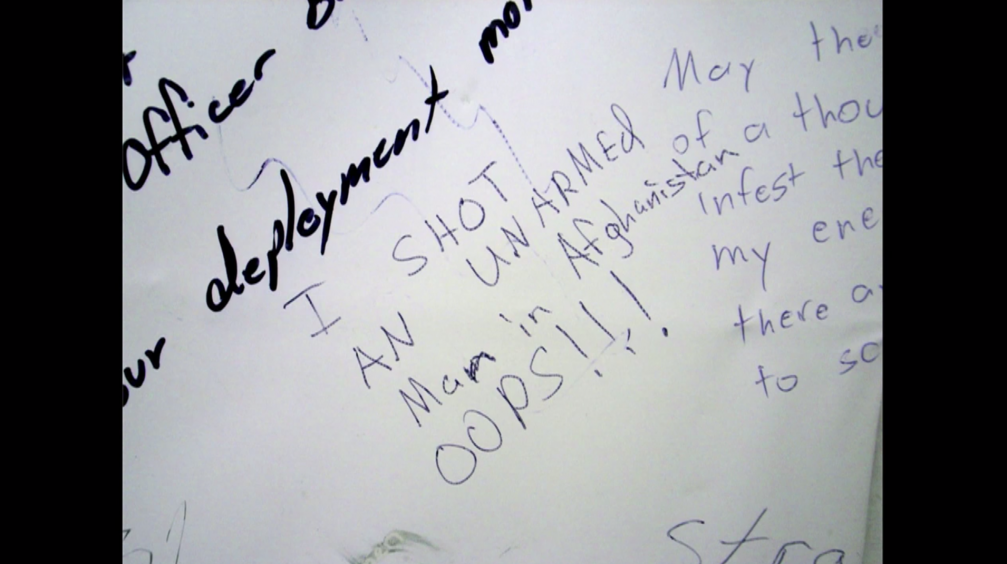

A project that struck me was Peter van Agtmael’s coverage of Iraq and Afghanistan wars. He brought several thousands of pictures and hours of video footage to our table, because he wasn’t able to look at his own work anymore. We built a piece «2nd Tour Hope I Don’t Die» out of all this and the voice of Michael Herr, a Vietnam War journalist form the 70ies, who expressed the exact feelings Peter had. I’m rapt by this confusion of a young photographer confronted with war, where you don’t really know what’s going on and who’s your friend and who’s the enemy. Trying to express this emotional state and being close to that affects you.

What elements are crucial for building a great multimedia work?

You need to know what you’re talking about — it all starts with a good research and finding the right «ingredients» to talk about a subject. It’s like cooking. You need to be conscious of how to put it together, where to present it and who’s going to «eat» it. There are three main multimedia story formats: linear storytelling, going from one point to another and working in time, so it’s closely related to the cinematic story telling; interactive, where you navigate yourself through the story; and installation in a space, which is a great approach because we have powerful screens and technology enabling us to have media content outside its usual platforms. We can adapt their shape to any form we want and place it in a spot that already has a meaning. Also the sound composition can come in at any time. Sometimes the sound is treated as of a second importance, but it’s a very strong element. If you mix it with the visuals, the sound is always 50% of the message.

Creating a multimedia work is like cooking. You need to be conscious of how to put it together, where to present it and who’s going to «eat» it.

Do you believe the cinematic material to be more powerful means of expression than still photography?

There are strengths to every medium. In photography you have time to take a closer look, it has all the qualities, ambiguity, and you can make your own reflections. Cinema often has an overwhelming quality. The most different aspect is that cinema is time based. I think there is more experimentation in photography than in cinema, and it’s due to costs and expectations.

Multimedia is a powerful tool — it can intensify the message of the author but the work can also get lost in the endless possibilities. How to balance the digital possibilities of our time and a masterly multimedia photo story?

That’s exactly one of the main questions of today — how do you use all that? It’s about creating an interesting container. Telling the story with today’s possibilities is where your craft and skills come in to present it in the most beautiful but also respectful, fair and meaningful way, maybe across different platforms. One of the things I’m fascinated by is that we live in a globalised world, the languages of expression become similar, but still you can feel the cultural differences on the produced material.

Today it is about creating an interesting container.

What are the most visible differences between how Americans and Europeans use multimedia?

I feel there is a tendency in the US to entertain and to be very clear about everything. Often that can be a quality — there is not so much doubt left to the viewer and the information is condensed to the maximum. In Europe the entertainment aspect is not so dominant, which can sometimes make it too serious and not so attractive to watch, but at the same time there is a tradition of breaking and questioning the medium, narration and being sceptical about things, which can be very strong as well.

Because of the connection with Magnum you have worked with rather sensitive subjects. How freely can you play and interpret the photos, and utter your position?

Indeed you have to be very careful about what you do. It’s a responsibility to be fair to these images and the people behind them. As an editor you can add another layer that strengthens something, or on the contrary — takes the pressure off. Maybe the photographer has a big empathy for the war victims, and you can feel it, maybe someone else is more clinical and just records what’s happening, so to that material you can add a voice of a person connected to the war that expresses more warmth, making an emotional connection to the viewer. I would tend to the humanistic approach, but sometimes it’s better to choose other languages to actually make people think. Your job is to become invisible, and it needs skills to be as objective as you can in getting that vision across.

In this time of saturated visual, audible and multimedia information, it’s hard to come across something never yet seen. How to create something out of the ordinary and lasting?

Firstly, don’t get bothered by what other people do; if you really care about the subject, it will stand out. It’s also healthy to keep thinking about the changing media landscape without getting crazy and stressed out about it. The media has always changed, and by adapting and using that for your advantage to tell the story, there is a chance to create a strong piece. Often those who break the rules or take it a step further are developed professionals because it requires production skills to do something like that. They always have a strong content and they’re smart about how they deal with it, maybe also presenting it on a new platform or in a technical way.

The form needs to be attractive, that you want to see more and you’re sucked in, ready to deal with the content. The representation should always be truthful but also sensitive. It has to be artistic in a sense that you can connect to it immediately.

Viedokļi