Designer Sarmīte Poļakova specialises in material design — she creates new, sustainable, and, equally importantly, visually appealing materials from the residues of different industries. «Waste is our own invention,» says Sarmīte. She looks for ways to turn it into new resources through design. This year, Sarmīte and designer Māra Bērziņja’s biotextile (Un)woven, made from recycled textiles, received the Grand Prix of the National Design Award of Latvia.

I imagine that material design is a complex process. Tell us about the specifics of creating new materials!

When I start working on a new material, I always start by exploring the resource: how I could use it, what it could look like, what is the potential that I can bring to this resource through design. There’s a concept called material-driven design — it means that it’s the material that determines what the design will be. Often we imagine a function for a material and then we try to squeeze it into that function, even if it doesn’t work. By putting the material at the forefront of the design process and studying it thoroughly, the result is more natural and authentic.

Most of the time, working on a new material starts with experimentation on a small scale. It is important to understand what happens to the material when it is stretched, cut, sewn, or glued. I work very systematically and always write down the results of my experiments. From these, I can further deduce what should be added to the material to improve it.

This approach is different from the conventional view of design — here’s the problem, here’s the solution.

Someone once told me that there are two ways to work in design: either you have that «itch» and creative urge to express yourself that doesn’t really have a reason, or you want to solve problems with design. I’m definitely one of the people with the itch. For me, design is a means of expression to convey my observations about things. Of course we all know about the global problems, but if you try to solve them, you risk missing other issues that are just as important.

When you create new material, how often does it happen that nothing comes of it? At what point do you abandon the experiment?

Biomaterials have recipes, so failure is relatively rare. Usually, a material can be improved by adding something or changing an ingredient. A biomaterial consists of fillers or fibres, a binder, which is an adhesive of different origins — it can be gelatine, cellulose, algae, or starch —, and a plasticiser. The more you work, the better you understand where the problem of the material lies.

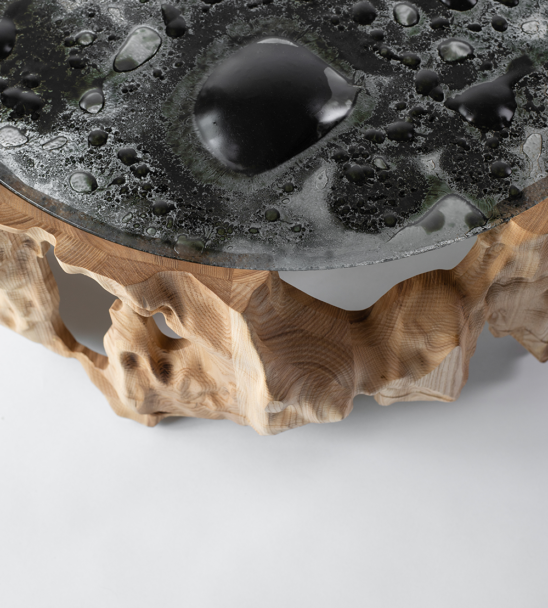

Sometimes the solution takes time. This was the case, for example, with my pine resin material. I thought I couldn’t use it anywhere, that it wouldn’t work, but I had this itch, and I wanted to keep trying. When I changed my approach to the material, suddenly it started to work. There is a time for experimentation and a time for reflection — you get attached to something, ok, it doesn’t work, put it on the shelf, try again later.

Your studio focuses on transforming production residues into new materials. How do you choose which resources to work with?

It’s quite random. For example, this is the case of the textile project that came to me in 2020. Before that, I was known as «Sarmīte, who works with pine bark». I wanted to prove that I could work with other materials too. Even though Māra and I had studied together and are good friends, we hadn’t worked together professionally, but we wanted to give it a try. We took part in a European Union project on fast fashion, and that led us to textiles.

When I was researching the industry, I realised how big a problem it was, and I decided that I could experiment with textile waste. At one point we came across recycled denim dye. It was a beautiful experiment that I posted on Instagram. This one post brought a lot of interest — we were invited to participate in various exhibitions and projects. It turns out that this is a topic that is relevant to a lot of people. When you start working on a new topic, it can bring new opportunities that you didn’t even imagine.

Tell us more about Pre-loved or (Un)woven! What makes this material special?

With (Un)woven, we are trying to make textiles that can be recycled over and over again, rather than just extending their life cycle by one more function. Textiles are a very hot topic at the moment, and many people are working in this field. Mostly, textile waste is used to make various insulation materials, which are much thicker, while thinner materials have more binders — textile scraps are impregnated with different starches — and are more like plastic. (Un)woven is soft and flexible and feels like rice paper. It can be used for furniture, screens, and drapery, as wallpaper, or for paneling. We are happy to let architects and designers test our material.

The visual appearance of (Un)woven is also important. Most biotextiles are available in a limited range of colours, such as denim blue or black and white. We use a variety of natural colours in our fabrics, which makes them more visually appealing. People are usually surprised to find out that (Un)woven is a recycled material.

You have also tested (Un)woven in various collaborations. What have they brought to the project?

In the beginning, when we positioned (Un)woven as a material for clothing — from fashion back to fashion — we collaborated with Mareunrol’s. This design duo is unique in Latvia, and they have always been my idols, so I wanted (Un)woven to be tried out by them specifically. The material really took centre stage in Mareunrol’s design — its flexibility, thickness, and texture, as well as its circularity. Our collaboration created two functional vests in different sizes, the smaller one made from the leftovers of the larger vest. This demonstrated the recyclability of the material — the off-cuts from the large vest were returned to us, shredded, and recycled again into new material for the small vest.

The collaboration with Vitra and Levi’s, which started quite by chance, brought a lot of publicity. The curators from the Netherlands had seen our fabric and thought it would be a good fit for the project. The harsh reality is that big brand names are very important. The moment I can put Vitra and Levi’s on my client list, it takes us to the next level.

In my conversations with Vitra, I tried to find out whether they were also testing new materials and working with material designers. I wanted to understand how complicated it would be to work with innovative materials for a company as big as Vitra, for whom it is very important to be able to guarantee 20–30 years of perfect quality for their customers. Often with new materials this is not possible.

New materials require a paradigm shift. For example, we could look at the circularity rather than the permanence. How can designers help change our perceptions?

Designers could certainly communicate this better in their concept. For example, how many twenty-year-old chairs do you have at home? It doesn’t fit our lifestyle anymore. Carpet manufacturers come to mind — more and more companies are not selling you a carpet once but providing a service. For example, every year they will come and replace the carpet or repair it. It is a dialogue between the product, the designer, the manufacturer, and the consumer. Not to give something away, but to have a service relationship with your customers is even beneficial for the company.

Another thing designers can do is to be open about the longevity, the good, and the bad qualities of their material. In a way, it’s also about creating and building a language, because sometimes the right words to describe a material are missing. We have to try to find new ways of talking about materials. I do not believe that the responsibility for more sustainable choices should be placed solely on the consumer. It is also the responsibility of producers to offer more sustainable choices and to educate the public about them.

When presenting the award to you, the jury of the National Design Award of Latvia 2024 noted that (Un)woven gives a positive outlook on the future of the textile industry. When thinking about sustainability, it is often characterised by a narrative of giving something up and sacrificing something.

I think it is important to show positive examples. Everyone is tired of the word «sustainability». And I would like us to stop stressing that already. Everything we create should be thoughtful, functional, beautiful, and, of course, circular. It should be a given.

There are many concepts and ideas for different biomaterials, but they rarely make it to the consumer market. What are the main challenges preventing the commercialisation of such materials, and how are you doing with that?

We have seen that almost anything can be made — there are materials made from potatoes, bones, and concrete — but they are all small samples. Now would be the time to show that such materials can work on a larger scale. I think designers and architects are very open to using biomaterials in different spaces that don’t have a very long lifespan, such as shop windows, interiors, and installations. There is a lot of interest in creative concepts, new textures, and experimentation. Material designers themselves should look for ways to show materials on a larger scale, to be more daring.

As far as the commercialisation of (Un)woven is concerned, we are slowly moving in that direction. The recipe for the material is constantly being improved; we need to understand exactly how to produce it, who can take it on, and how much it costs. At the moment, I am trying to assemble an «army» that can drive these processes on the business side, on the chemical and production side, and on the design side.

How do you see the future of materials? How can we get to the point where we are all using only biomaterials?

To get there, we would need to develop an internal resource infrastructure. For example, in a café, all the used coffee is collected separately; there is a company that collects it from all the cafés in Riga. At that point, it is no longer waste or leftovers but a raw material. Waste is, in general, something we invented. It is funny that at one point we have food on our plate, but when it is eaten, we say, «Eww, that bone is garbage, I don’t want to touch it». There is residue in almost every industry, and we should collect it and recycle it.

There are already movements like this in the Netherlands and the US, for example. It needs both entrepreneurial people and systematic support to make it work. Legislation can also encourage it. The widespread use of the new materials still requires a lot of research, time, and investment. However, I believe that new materials will go where plastics are today because this is a very hot topic — there are various funding instruments and investors available. In addition, economic forecasts show that this area will continue to grow rapidly.

Of course, ambition is also important. When I visited the Latvian State Institute of Wood Chemistry, I discovered so many great materials, and there is also a lot of research on innovative materials at the Riga Technical University. It seems — why do we hear nothing about this? Something should probably be changed in the system so that we see these materials around us, even if they are not perfect yet.

You can follow Sarmīte’s work on the Studio Sarmīte website and Instagram account.

Sarmīte and designer Māra Bērzina’s biotextile (Un)woven received the Grand Prix of the National Design Award of Latvia 2024. In the 2025 competition, Sarmīte is one of the selection jury category chairs who will lead the evaluation of works in the product design category. The autumn application period for the National Design Award of Latvia 2025 has been extended until November 30.

Viedokļi