At the end of October, Dutch Design Week (DDW) took place in Eindhoven, inviting visitors to exhibitions and events, as well as designers themselves, to imagine a better future. From speculative ideas to art objects, from craft skills to artificial intelligence, design at DDW demonstrated respect for the environment, diversity, and creative freedom.

DDW is one of Europe’s most prominent design events, with an emphasis on experimental design and conceptual approaches. Glossy product designs take a back seat to new ideas that may not be perfectly polished but are rooted in meaningful reflections on the nature and role of design.

This year, DDW took place in 110 different locations in Eindhoven, with more than 2600 designers participating. To help visitors navigate the wide range of exhibitions and other events, which is truly quite varied and far from easy to grasp, the programme is divided into several themes or design missions, inviting them to explore: our equal future, health and well-being, our digital future, our living environment, and our thriving planet. It is already clear from the list of themes that sustainability, an issue that is being raised more and more in the field of design but has become almost a background sound in the noise of greenwashing, is omnipresent at DDW. However, this undeniably important topic rings true at DDW, with fresh perspectives and a willingness to discuss and take responsibility for one’s choices.

Young & free

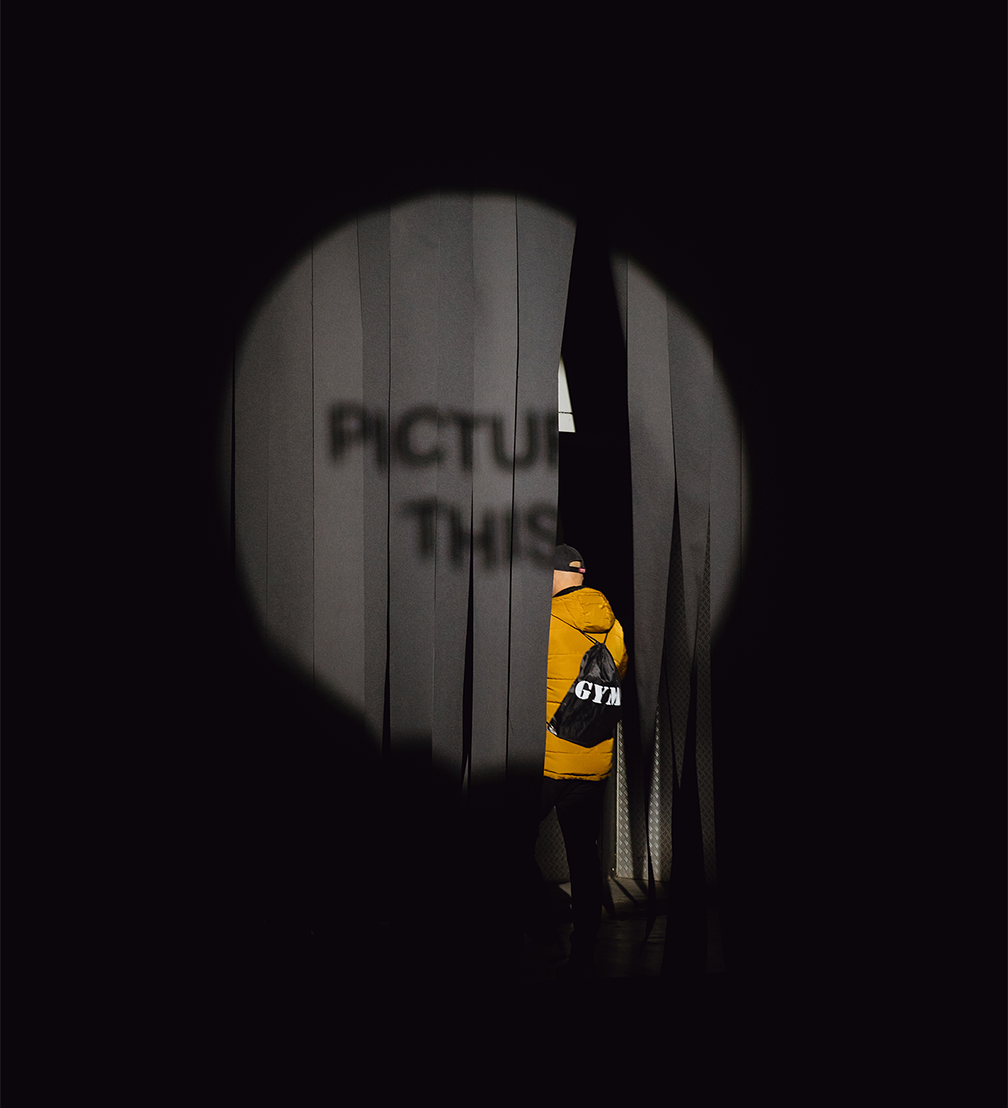

One of the highlights of DDW is the graduation show of the Design Academy Eindhoven (DAE), where the roots of this design event lie. With the aim of introducing young designers to entrepreneurs, the first Design Day was held in Eindhoven in 1998, and by 2002, it had grown into a week-long event. Design in Eindhoven seems to be of interest not only to design professionals but to people of all backgrounds and ages. The graduation show (as well as others) was packed, and it was not easy to make your way through the masses of visitors to get a good look at the work of young designers. DDW’s original aim of creating a platform to introduce young designers is still relevant today. Most of the young professionals are eager to strike up a conversation, talk about their work, and have also prepared business cards and QR codes for their Instagram accounts.

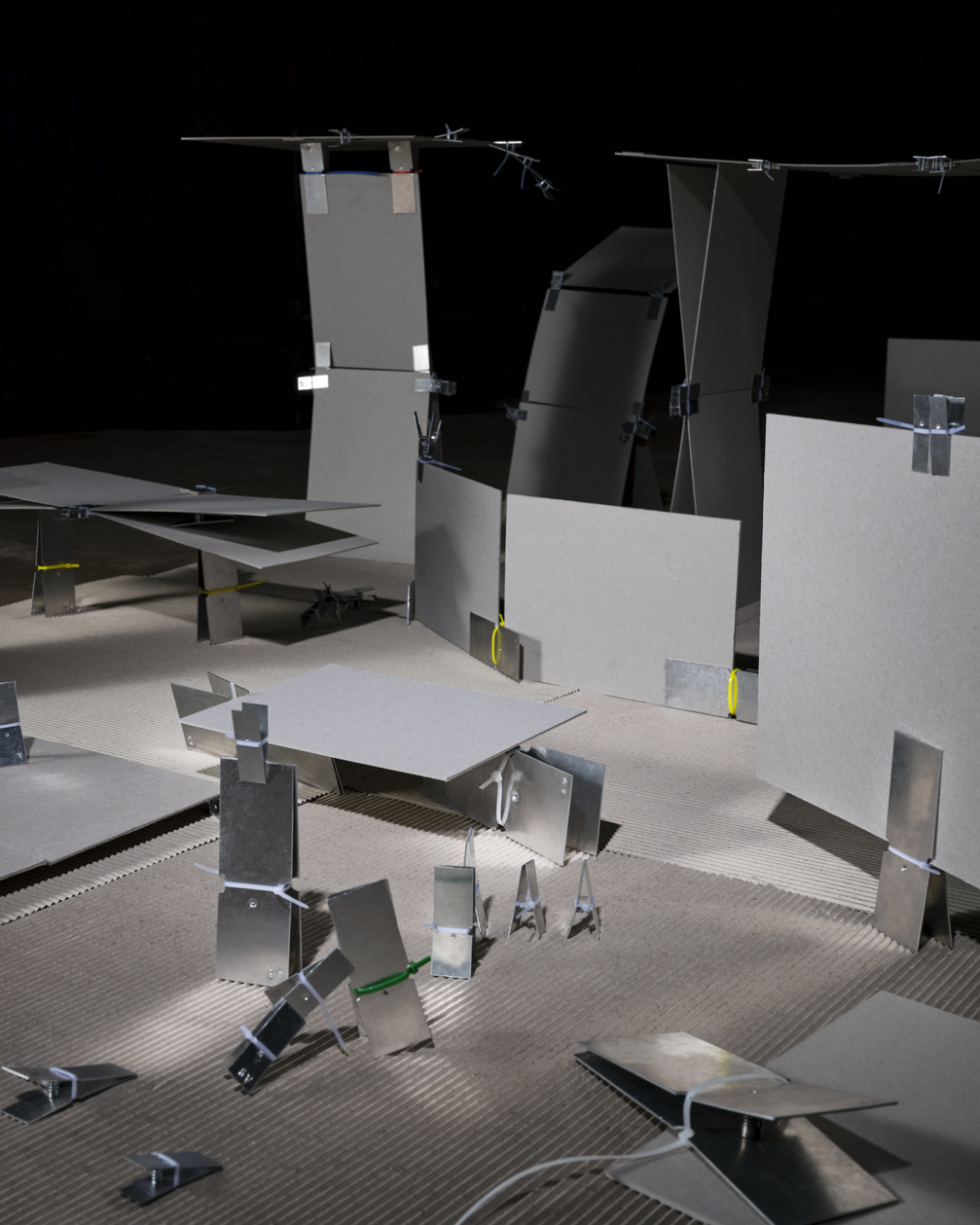

Students have tackled a wide range of topics in their work, putting issues in a broad context and not being afraid to discuss current, yet uncomfortable or controversial issues. For example, Berta Grau Sánchez’s video essay comments on the interface of a pornographic website and its videos from a feminist perspective, while Amalia Magril, who created tree-planting tools, explores the Israeli practice of planting pine trees to replace native flora, drawing parallels with the country’s identity, culture, and politics. Among the many conceptual projects, there are also some rather practical solutions. Inventive solutions are offered by Louise Dousset, who has created a new design for paper clips that can be easily produced in different quantities and scales, and Paul Gödecken, who proposes drying timber by using it to create temporary furniture for public spaces. Humour and provocation are present in many of the works (for example, Luca Cous’ sculptural objects contemplate the «aesthetic possibilities of scrotums»), but the students are serious about the themes they explore. Isn’t it wonderful that the learning environment and society respect young people enough to allow them to make their own choices?

Many of the projects of international students are related to the search for identity and their home countries, which is also the focus of DAE graduates from Latvia. Dārta Maija Zēģele interpreted Latvian customs, such as fortune seeking in lilacs, in accessories, while also offering a recipe book of traditions that would allow us to preserve the Latvian way of life and pass it on. Felicita Gāga has created a digital dress that combines Latvian national costume with the information noise on social media, reminding us that cultural heritage is formed not only in the past but also in the present. Pēteris Zilberss invites people in the Baltic region to reflect on their eating habits and the devastating impact of agriculture on the Baltic Sea by presenting an installation in which a kitchen is slowly overflowing with algae water. Dace Sūna has also created an engaging installation, her project focusing on universal truths rather than national particularities. The work is a meditative experience that encourages reflection on our relationship with life and death.

Design for strong communities

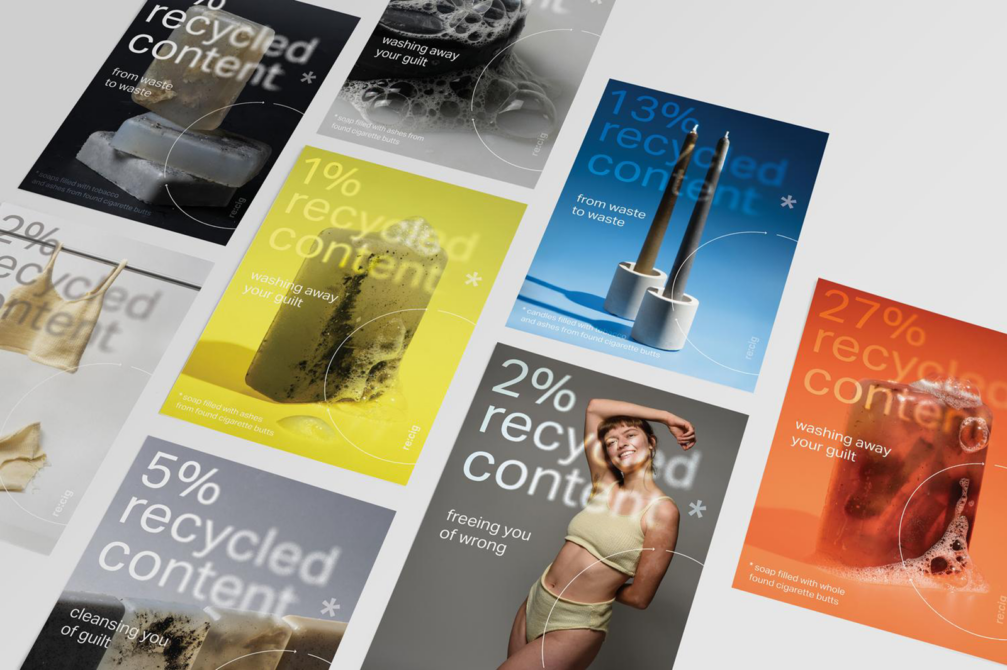

It is noteworthy that the DDW showcased not only the work of DAE students but also a number of projects from other European design schools (including the Vilnius Academy of Arts), which were on display in the Klokgebouw building. One of the works that stuck out with its ironic message was Leila Wallisser’s graduation project at the Weißensee Kunsthochschule Berlin. Speculating on the recyclability of cigarette butts and incorporating various parts of cigarettes into soaps, candles, and even underwear, the young designer warns us about the negative consequences of greenwashing and asks us to consider whether recycling a material is sometimes more damaging than manufacturing it.

Alongside the projects of young designers, the Klokgebouw building showcased sustainable products and innovative brands, as well as services and projects that could help build a better future. Here, you could see everything, from furniture made from recycled fire hoses to a digital tool that helps cities identify and map problem areas or, alternatively, places that might be of interest to investors. It is difficult to extract a single message from the rich variety of the exhibition, but it does reflect the many roles and broad spectrum of design.

A variety of design projects were also on display in the Microlab Hall, though in a less saturated (more immersive) way. Here, visitors could become Ministers of the Future by expressing their views on different future scenarios, explore the Dutch Design Award exhibition, or choose their favourite model of a mycelium coffin. Microlab also showcased many projects related to strengthening communities and equality. Mina Abouzahra, a Moroccan designer from the Netherlands, presented the Bedouin rugs she makes with a collective of women artisans in Morocco, providing good working conditions and fair wages for the weavers. In response to Iranian women’s struggle for equality, RV Collective, the creators of Crafted Liberation, have made stadium seats out of headscarves, transforming a symbol of oppression into a hope for Iranian women’s future full participation in society, including sporting events.

A strong community is also a defining characteristic of the Dutch design ecosystem. This was evident in the DDW atmosphere and confirmed by talking to local designers. During my visit to the exhibition at the design hotel Kazerne, its founder Annemoon Geurts told me that the aim of the place is to provide a platform for young designers and to create an environment that demonstrates the power of design to the public. The exhibition at Kazerne featured a variety of unique design objects, which Annemoon, although she selected them herself, did not shy away from criticising, for example, for choosing less environmentally friendly materials. Such openness and the ability to respectfully debate without condemning wrong choices are surely preconditions for a strong and successful community.

The lack of respectful discussion is felt in Latvia’s divided society. Almost every day, heated debates on various issues erupt among us, becoming especially hostile in the digital environment. However, this is not just a Latvian problem — the marginalisation of society by social media and fake news is seen all over the world. This theme was explored by fashion designer Tevin Blancheville in his collection shown in the Manifestations exhibition. The designer has embodied characters such as the Doomsday Prepper, the Concerned Citizen, the politician who fuels hatred, etc. Tevin points out that despite the gloomy situation in the world, his clothes are made with hope, a reminder that we can all fight for a freer, fairer, and more prosperous society.

Technology changes, people remain

Our relationship with technology was the main focus of the Manifestations exhibition, which the participants approached from different angles, also addressing the human aspects of digital space and merging the physical with the virtual. The exhibition featured a contemplative documentary short film, Hardly Working, by the collective Total Refusal, which follows non-player characters (NPCs) in video games, drawing parallels with real society, which often chooses to leave certain groups in the shadows. Nonna Hoogland, an illustrator and ceramicist, has interpreted the unchanging nature of humanity in striking vases that look at ancient Greek myths from a contemporary perspective. Indeed, the story of Narcissus resonates with our collective obsession with selfies.

Given the rapid breakthrough of artificial intelligence (AI), DDW featured many works dedicated to this technology. Dramatic speculation about which professions will soon be eradicated by AI is common in the public domain, but there are other relevant questions. Such as, how much can we trust AI with? This question was addressed by Jules Sinsel, who used an interactive installation to visualise data on the low accuracy with which AI determines whether prisoners should be released early in the US. Despite the work’s sinister and technological appearance, it turns out that each of the modules, which close or open depending on the AI’s decision, is in fact a hand-folded origami of paper. AI is seen from a different perspective by artist Milo Poelman, who, in conversation with AI chatbot Textdavinci-003, seeks answers to questions about whether AI could be considered a new life form and how we can have an honest and non-exploitative relationship with technology.

When creating a design, it is common to think that it should provide a solution to a problem. But the challenges we face can be so complex and contradictory that it can be difficult to give a practical answer. We would like to think of design as this wonderful tool whose creator has meticulously thought through all of our needs and wrapped them in a sexy package, but in a turbulent world where war is raging, the climate crisis is looming overhead, and the divide between different groups in society is growing, we should re-evaluate the mission of design. Maybe design doesn’t always have to give us an answer. Maybe it is enough that it asks us a question.

Viedokļi