Salaspils 7th Preschool Educational Institution is the first public building in the Baltics to receive passive house certification. Designed by MADE Arhitekti, the kindergarten is constructed from wood — a locally available and sustainable material. However, outdated fire safety regulations currently hinder the use of wood in public buildings in Latvia. In this project, the architects found alternative solutions that enabled them to create a sustainable, safe, and pleasant environment for children.

As young families increasingly relocate from Riga to nearby municipalities, Salaspils faced a need for a new kindergarten. To ensure a sustainable, attractive, and functionally well-thought-out architectural solution, the municipality announced an open design competition in 2018. From the outset, the competition required the new building to be energy-efficient, rational, and adaptable to various usage scenarios. The authors of the winning project, MADE Arhitekti, note that the client’s strategic vision encouraged them to take a broader perspective, exceeding the construction standards currently mandated by law.

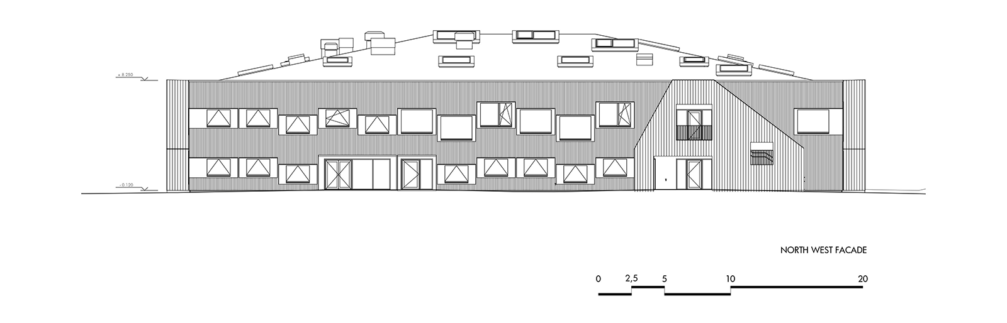

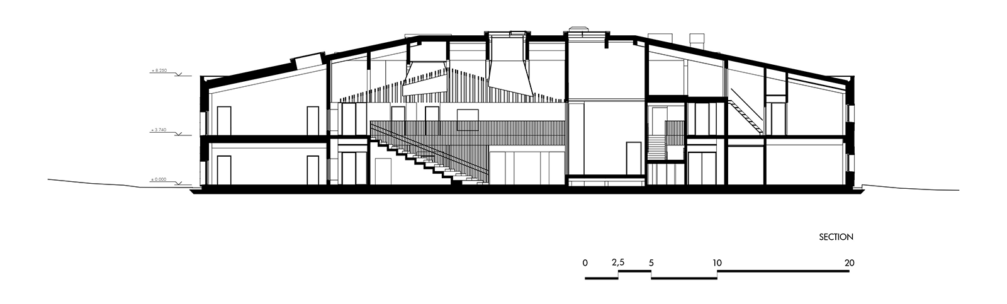

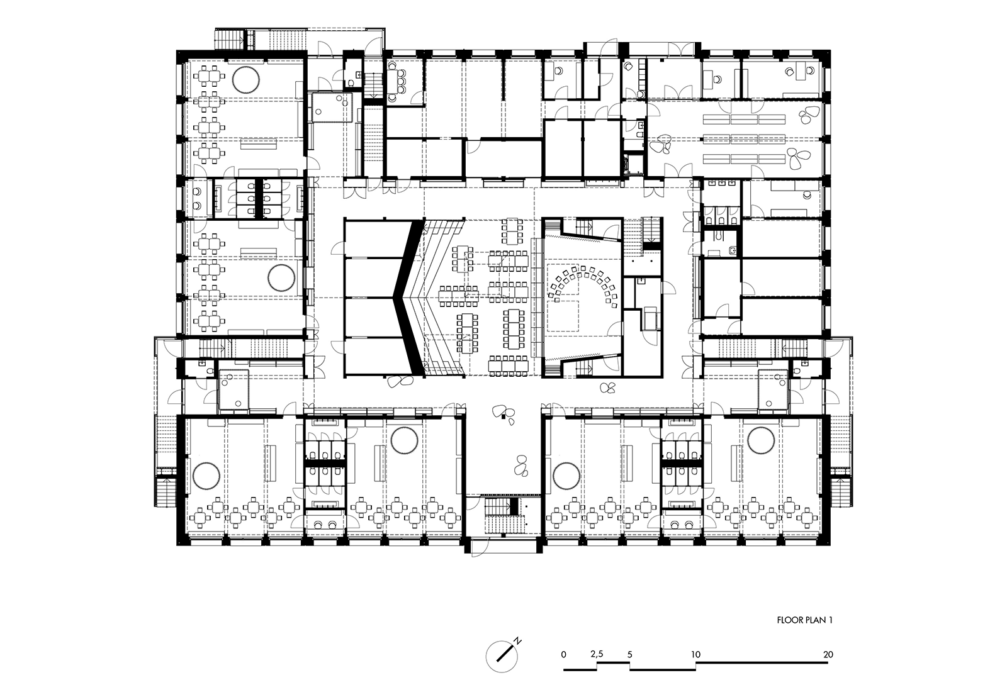

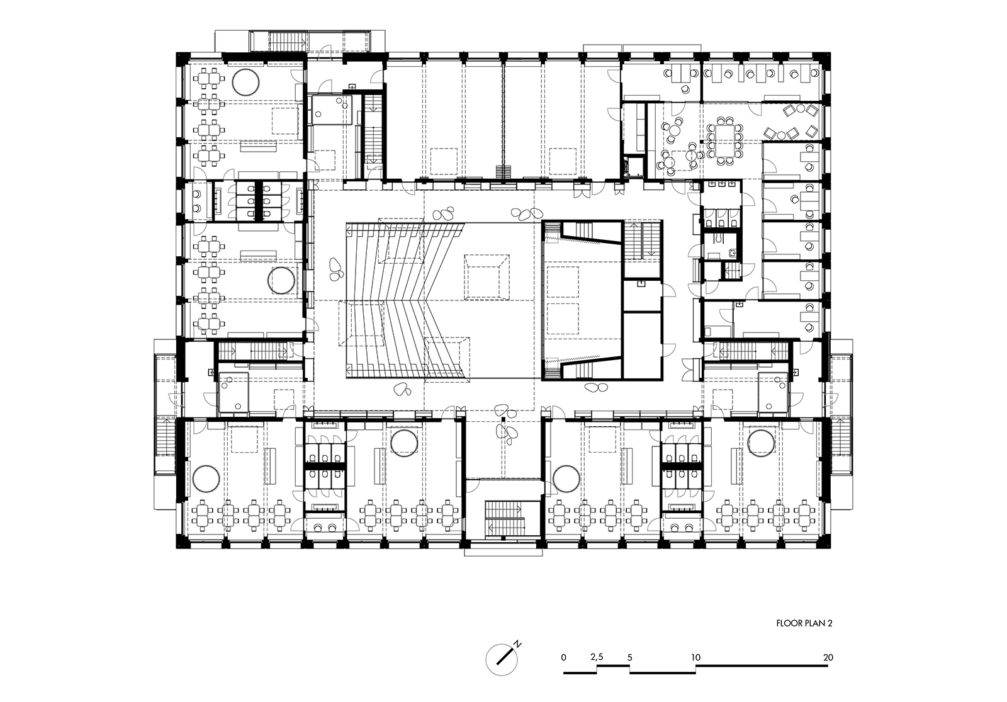

The kindergarten is designed as a two-storey building, housing a total of twelve group rooms (or classrooms), arranged in pairs. Each pair has a separate entrance from the outside with its own entrance hall. This decentralised access not only provides a safer evacuation solution in case of emergencies but also simplifies daily logistics, especially during drop-off and pick-up times. The entrances are marked with profiled metal «houses» that contrast with the wooden cladding of the building facade. All group rooms are arranged around a central «living room» with an amphitheatre, which can be used as a dining area or event space. Adjacent to this central hall is a music room, which can be combined with the main hall and amphitheatre during events.

The proportions of the group rooms and their spatial connections were designed with both current and future needs in mind. One of the municipality’s key requirements was the flexibility of the spaces, allowing them to be repurposed as a primary school if necessary, given that municipal needs may change over time. MADE Arhitekti addressed this by designing spacious group rooms that could easily be converted into primary school classrooms without the need for significant modifications.

The Salaspils kindergarten has received an energy efficiency certificate from the Passive House Institute in Germany, making it the first certified passive public building in the Baltics. Both the structural and finishing elements of the building are made of wood. Along with the building’s overall form, the use of wood has ensured excellent energy efficiency and a low carbon footprint. According to MADE Arhitekti, the Salaspils kindergarten consumes almost four times less heating energy (12 kW per square metre per year) than the nearly zero-energy building standard set in Latvia (45 kW per square metre per year). It is estimated that the kindergarten’s construction materials account for 724 tonnes of carbon emissions. However, considering that the timber used in the building stores 1,232 tonnes of carbon, the building can be regarded as climate-positive while it remains in use. Another crucial aspect in material selection was children’s health — the architects chose interior materials with minimal emissions of volatile organic compounds and without toxic components.

Current legislation in Latvia requires new public buildings to achieve nearly zero-energy efficiency levels, which was also MADE Arhitekti’s initial goal when designing the kindergarten. The client also believed that achieving passive house standards would be too costly. However, during the construction process, the architects realised that the building could achieve high energy efficiency ratings. To meet the passive house standard, architects have to use a holistic approach, utilising both architectural tools, such as the building’s form and layout, and high-quality building components, including windows, insulation, and ventilation systems, as well as achieving a high standard of construction quality. The latter was a decisive factor in meeting the passive house standard for the kindergarten project, which achieved outstanding results in the blower door test. Moreover, the passive house standard was achieved using mostly locally available technologies. For example, windows and doors were produced locally in Salaspils.

The architects emphasise that high energy efficiency and sustainable architecture, which utilises renewable resources, do not necessarily lead to significantly higher costs. MADE Arhitekti compare the kindergarten’s construction costs to those of a recently built supermarket in Salaspils, which has a slightly smaller area. While the kindergarten cost approximately 8.3 million euros to build, the typical «box» of supermarket, which relies on fossil-based materials, was constructed for 8.5 million. «This is not a question of money; it is a question of will,» emphasises architect Miķelis Putrāms.

Outdated regulations — a barrier in the way to climate neutrality

According to MADE Arhitekti, the solutions used in the kindergarten address the key challenges in contemporary construction: how to build economically, in a way that is good for the planet and safe for people. However, achieving sustainability goals, including climate neutrality by 2050, is hindered by existing regulations. «I believe that the construction standard LBN 201–15 Fire Safety of Buildings has been holding back the industry from developing zero-emission construction for 15–20 years. These regulations are a major barrier preventing the use of timber and other sustainable materials capable of storing carbon. In the Salaspils kindergarten project, we managed to «break through» this regulatory barrier and implement a modern fire protection concept,» explains Miķelis.

He points out that constructing public buildings from wood in Latvia is practically impossible. For instance, according to fire safety regulations, it is prohibited to build a two-storey wooden kindergarten. «This is understandable from a safety perspective, as children cannot evacuate themselves from the second floor. However, from a cost and energy efficiency standpoint, constructing a single-storey kindergarten is extremely irrational. Our analysis has shown that existing single-storey kindergartens are not even worth insulating — it is more cost-effective to demolish them and build a new, compact two-storey structure instead,» says Miķelis.

The architect stresses that fire safety solutions in Latvia are not addressed in a meaningful way but are instead blindly dictated by regulatory requirements. Upon closely examining the building code, MADE Arhitekti identified multiple contradictions and sought clarification from the Ministry of Economics, which is responsible for construction regulations. The ministry responded that deviations from fire safety standards could be approved by the technical commission of the State Fire and Rescue Service (VUGD). To develop a set of solutions that enabled the construction of a two-storey wooden building, architects involved engineers with extensive experience with fire safety in timber buildings — structural engineer Gatis Vilks and Edvīns Grants, head of the Research Centre at the Forest and Wood Products Research and Development Institute. Working together with specialists of VUGD, they met all safety requirements by creating more accessible exits, shorter evacuation routes, and smaller fire compartments, ultimately making the Salaspils kindergarten even safer.

Miķelis notes that the experience gained during the approval and design process highlighted the need for architects to take safety requirements more seriously and to understand potential fire hazards and risks. He points out that merely complying with building regulations does not guarantee safety: «The building code basically allows you to design a building that will not collapse for half an hour in a fire, but during that time, people may not be able to escape.» Firefighters view regulations solely from a hazard perspective, while architects often fail to grasp the importance of safety considerations. The situation is further complicated by the lack of fire safety engineers in Latvia who could assist architects in developing safer solutions. Miķelis emphasises that the existing regulations should be revised with input from both local and international experts experienced in developing modern, flexible safety solutions. «The building code regulates standard situations. But architecture is too creative to be confined to strict regulations. If we were building very primitive structures, this regulation might be suitable. But today, when we are designing much more intelligent and complex buildings, these regulations fail to ensure safety in modern, well-thought-out public spaces.»

Architecture and interior by MADE Arhitekti. Structural engineer — BICP. HVAC by EIPB. Lighting consultant — Bartenbach. Passive house consultant — Tommy Wesslund. Energy calculations and simulations by Mare Mitrēvica, Ruta Vanaga. Fire protection solutions by Edvīns Grants. Lanscape architecture by Alps Ainavu Darbnīca». Roads and squares by IE.LA Inženieri. Acoustics — Jānis Tālbergs. Builders — Merks, Pillar Contractor.

Viedokļi