As we reflect on the role of significant mentors in the lives of architects, we sometimes come across visionary individuals who are worth a closer look. One of these unique figures is the Latvian-born architect and educator, Astra Zariņa, who has inspired generations of architects around the world. Zariņa’s vision of the urban environment, the value of historical heritage, and the role of culture in architecture was groundbreaking in the 1970s and resonates with contemporary ideas of sustainability. Igors Malovickis, architect and researcher, co-founder of Arhiteksti, writes about Astra.

Zariņa’s name came to our attention on a quiet evening in July 2022, when a lecture recording was shared in the Arhiteksti group chat, along with enthusiastic posts about the newly discovered Latvian architect. The lecture was part of a series titled Architects, not Architecture and featured American architect Steven Holl who shared memories and stories about various important events and personalities in his life, including one of his most important mentors, Astra Zariņa, who ran a foreign studies programme at the University of Washington in Rome, where Holl studied.

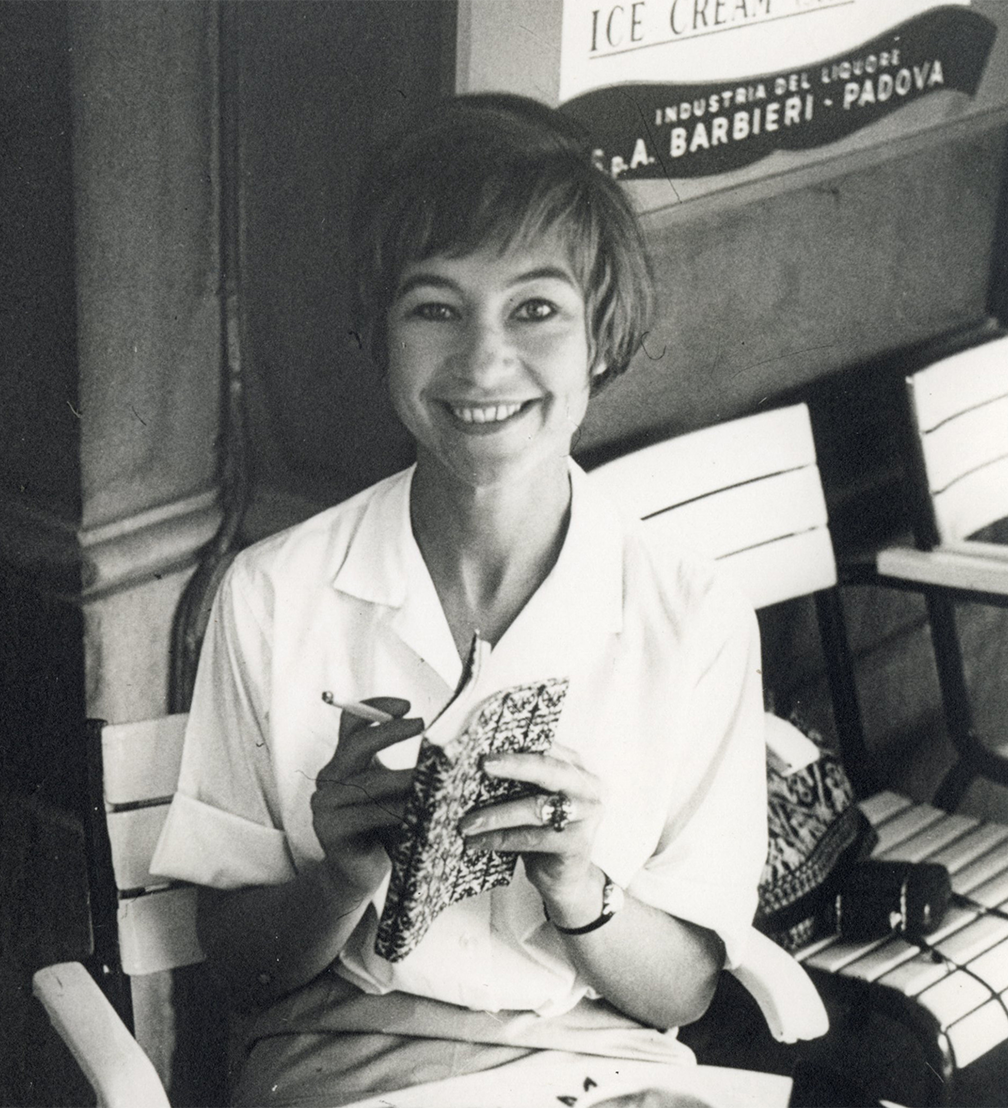

Astra Zariņa was a true citizen of the world. She was born in 1929 in Riga, but the beginning of the Second World War forced her family to emigrate from Latvia in the early 1940s. After fleeing to Salzburg, Austria, and then spending several years at a refugee camp in western Germany, Zariņa and her family finally sought political asylum in the United States and settled near Seattle. She enrolled at the nearby University of Washington School of Architecture in 1951 where she studied with excellence. During her studies, she began working as a draftswoman at the office of the renowned Seattle modernist architect Paul Hayden Kirk. In 1955, she graduated with honours from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), becoming the first woman in MIT’s history to graduate at the top of her class. Astra then moved to Detroit, the epicentre of 1950s modernist architecture in the USA, where she worked as a project designer from 1955 to 1960 with Minoru Yamasaki, the renowned Japanese-American architect and designer of the Twin Towers in New York. In his 2017 biography Minoru Yamasaki: Humanist Architecture for a Modernist World, Zariņa is described as «perhaps the most talented artist to ever work for Yamasaki». Working for Yamasaki was special because another prominent Latvian architect, Gunārs Birkerts, began his US architectural career in Michigan in the 1950s. Birkerts joined the Yamasaki team in mid-1956 and became a colleague and close friend of Zariņa. Their collaboration continued later in Italy.

Despite her success, Zariņa did not want to limit herself to a career as an architect in Detroit. After receiving a Fulbright scholarship in 1960, she travelled to Italy, where she won the prestigious Rome Prize in Architecture of the American Academy in Rome, becoming the first woman to do so. Zariņa arrived in Rome as a convinced modernist, but the city changed her. The history, culture, and lively urban environment of Rome encouraged her to reconsider her long-held beliefs about the importance of socially active space and to focus on the preservation and revitalisation of the cultural and historic environment. During this time, Zariņa travelled extensively and explored other regions of Italy, especially the ancient Etruscan hilltowns in Tuscany. She was enchanted by the newly discovered places, notably the small hilltown of Civita di Bagnoregio, where the architect spontaneously bought her first house in 1961, a one-room building with a massive fireplace and a garden, where she spent much of the later part of her life.

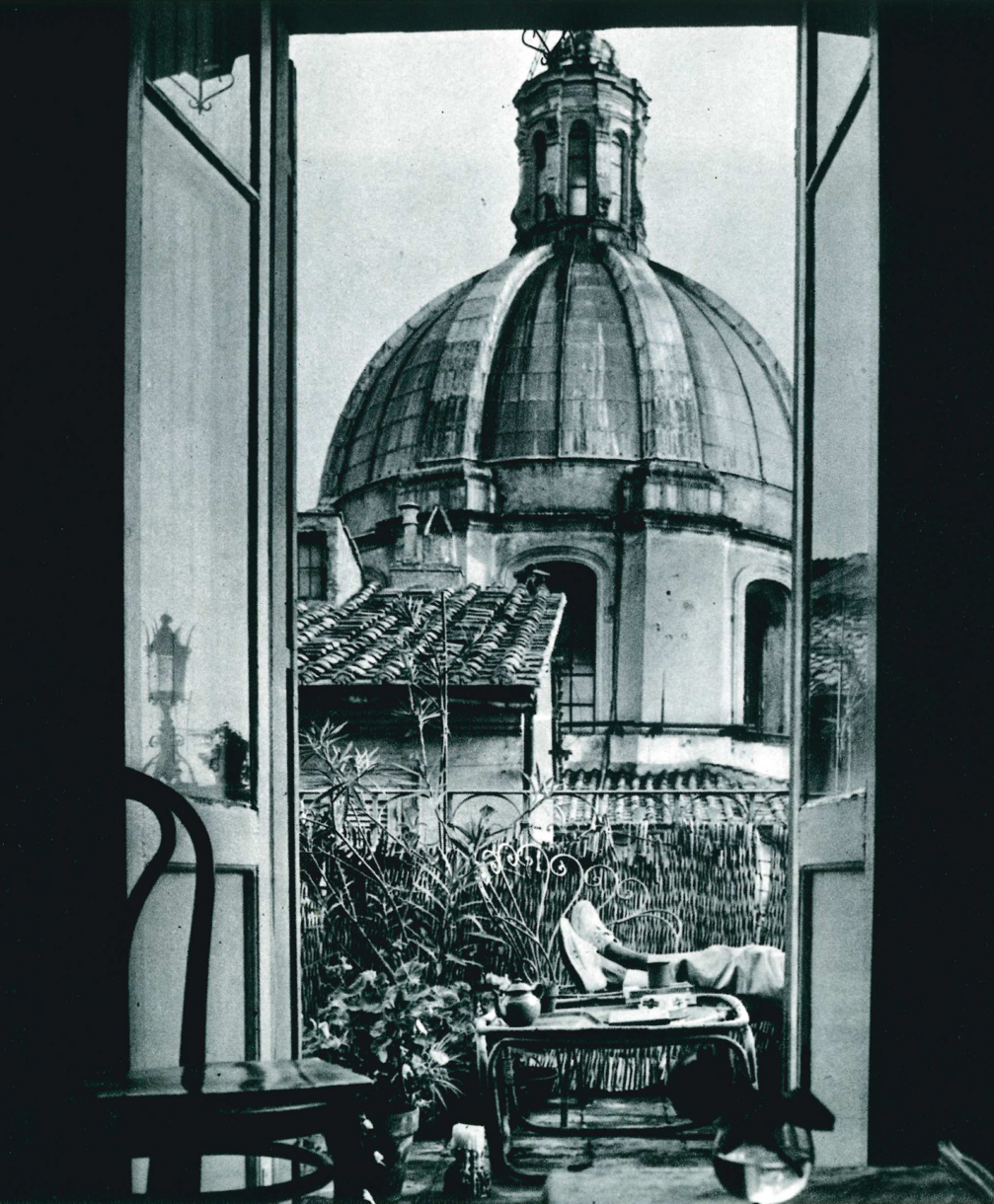

After Rome, Zariņa went to work on the Märkisches Viertel neighbourhood project in West Berlin, which turned out to be one of the last architectural projects she actively worked on before fully committing herself to teaching. After returning to the United States, she continued as a lecturer at the University of Washington and, in 1970, initiated the university’s Rome programme. In Rome, Zariņa hosted and taught American students, opening their eyes to the world and introducing them to the culturally rich and vibrant city. She believed that this experience, which made her rethink what she had learned at university, was extremely important. While living in Rome, Zariņa continued to actively study the city, and in 1976, in close collaboration with the celebrated Hungarian-American photographer Balthazar Korab, Astra published her seminal work, I Tetti di Roma: le terrazze, le altane, i belvedere, about the rooftops of Rome. In the book, she defined and analysed the concept of the roofscape, arguing that roofs both form a distinctive landscape above buildings and act as socially active urban spaces, challenging the traditional divide between private/public spaces and adding an additional functional dimension to the city. Zariņa was a pioneer of urbanism in her time. Her argument was accompanied by a visual essay on the roofscapes of Rome and their social life by Balthazar Korab.

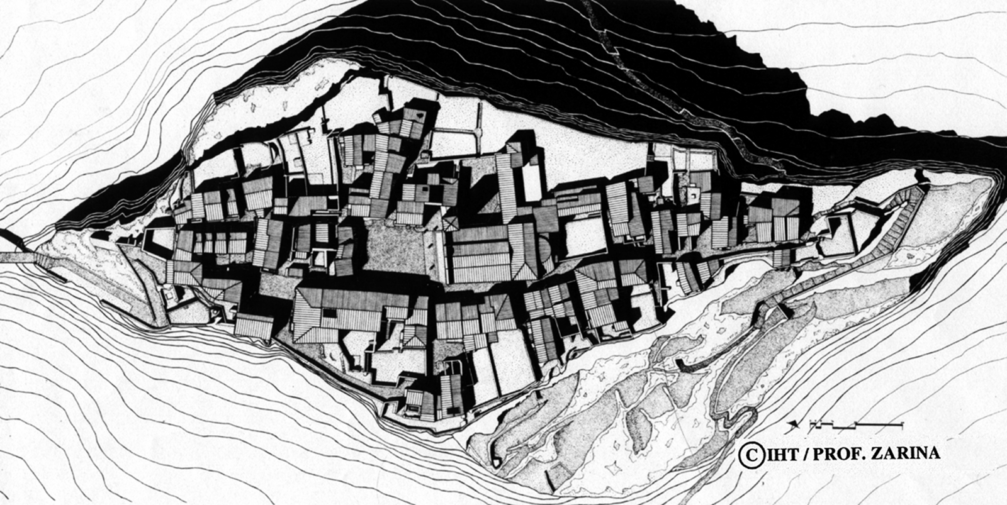

One of Astra’s most important achievements is her work on the restoration and preservation of Civita di Bagnoregio. Fighting for the fate of this «dying city» situated on top of a soft volcanic rock, Zariņa founded the University of Washington Italian Hilltowns programme in 1976 and the Northwest Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies in Italy (NIAUSI) or the Civita Institute in 1981. Alongside her preservation work, Zariņa was able to successfully persuade several well-known public figures to buy homes there, including her long-time collaborator and friend Gunārs Birkerts. Using the institute as a public platform, Zariņa and her husband, architect Anthony Costa Heywood, continued to educate students and the public until her death in 2008.

Astra had a fiery character and energy that could inspire anyone. Beyond her lessons on architecture and urbanism, Zariņa added another dimension of learning — culture. She knew how to immerse her students in her life of architecture, art, history, philosophy, culinary, and culture, for example by taking them to Italian classes every morning or by making them join her in cooking meals. Holl recalls Zariņa’s emphasis on the importance of food: «If you’re going to be an architect, the first thing you need to do is learn how to cook.» She also tried to encourage students to feel comfortable in different social situations. Zariņa’s «didactic dinners» involved sourcing fresh local produce from nearby markets, setting the table, serving snacks and cocktails, and hosting various guests in Rome. This approach, which some students later dubbed «architecture from city to spoon», was an integral part of her curriculum.

Reflecting on Astra’s legacy as an educator, Steven Holl summarised Zariņa’s core values. First is the value of urban space, which she helped her students discover through maps and fieldwork. While in Rome, Zariņa also noticed and conceptualised the peculiar and socially active roofscape, which revealed the urban fabric from a new perspective. Today, we are used to terms such as «adaptive reuse» and «conservation of the historic environment», but Zariņa, ahead of her time, emphasised their importance as early as the 1970s. Astra also saw the importance of community in architecture. On weekends, Astra took her students to Civita to help them imagine different scenarios for preserving the town. Zariņa was convinced that, in order to preserve the historic environment, it was important to preserve the myths and ceremonies associated with it. In restoring Civita, Zariņa also revived a number of historical traditions and customs of the town. In the spirit of a sustainable approach in a contemporary sense, Zariņa also drew attention to the value of earth, plants, and animals in the urban environment. Finally, Astra highlighted the value of organic food, its variety of colours, flavours, and textures, the presentation of dishes, and cooking skills.

Despite Astra Zariņa’s dazzling and cinematic career, her professional contribution and that of her fellow female architects have been marginalised in history. These blind spots in architecture were explored in the exhibition Rome and the Teacher, Astra Zariņa and the architecture conference Rixarch 2024: Blind Spot, organised by RISEBA University Faculty of Architecture and Design (FAD) and Arhiteksti Foundation. As we continue to bring Zariņa’s work to light, her book I Tetti di Roma is going to be re-published in English, followed by a translation in Latvian.

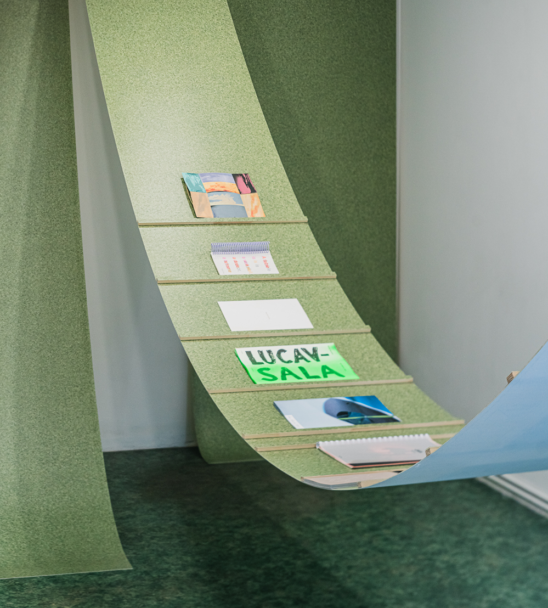

The exhibition Rome and the Teacher, Astra Zariņa, which was on view at the National Library of Latvia from March 14 to April 27, is a continuation of a process begun in 2019, in which Steven Holl and curator Alessandro Orsini brought Astra’s legacy and personality to light. Originally exhibited at the Holl-founded art centre ‘T’ Space in Rhinebeck, New York, and galleries in Cleveland and Seattle, it eventually travelled to Zariņa’s birthplace, Riga. The exhibition presented Zariņa’s research in Rome, early works and reflections on his teacher by her best-known student Steven Holl, as well as works created during the Civita 2023 workshop organised by RISEBA FAD and Arhiteksti. The exhibition was accompanied by a specifically recorded video lecture by Steven Holl and models of the planned memorial to Zariņa in Civita di Bagnoregio.

Concluding the opening event, RISEBA FAD dean Rudolfs Dainis Šmits noted that the exhibition’s journey to Riga started with a single email to Steven Myron Holl Foundation and encouraged the students and architects gathered to be courageous: «If you have an idea, be prepared to take a risk and act, because there will probably be no ready-made solution.» Alongside many students in the United States and Italy, Zariņa’s innovative approach and tireless energy now continues to inspire a new generation of students in Latvia.

Viedokļi