Gilma Teodora Gylytė is one of the founders of the Lithuanian architecture office DO Architects. Her belief that architecture and the urban environment should be human-centred has helped convert a series of outdated buildings into inviting places. Gilma is also promoting the transformation of Vilnius streets and public outdoor spaces into a more pedestrian-friendly environment. She has recently initiated the project Rebuild Wonderful Ukraine, which brings together Lithuanian and Ukrainian architects to share experience in the regeneration of Soviet architectural heritage.

Transformation seems to be one of the key elements in the architectural practice of DO Architects. Can you tell us more about it?

I see transformation as a continuous process throughout generations. It is beautiful evidence of the constant growth of human beings. Every generation and every human being puts their work and intelligence into judging what is valuable to keep and what is valuable to add.

This philosophy unites us as a team. Together, we find meaning in creating positive change in our surroundings. Our office connects many young creative architects, and we seek to make our surroundings and our habits better. And transformation for us just seems a natural way to achieve it.

We also believe we must live and lead by example. We set up our offices in places which we then transform, acting like urban seed ourselves, and when we change the surroundings, we move to the next place. Now we have just moved to a place where we need to transform not only the building, but the whole territory.

Transformation and regeneration are also among the main themes when discussing the future of our cities and living environments. How do you see the role of transformation in architecture and urban planning?

I think about it in terms of authenticity and rationality. As architects, we always strive to find the character of a building and a space — we want it to be moving so it would touch other people’s souls. It is done by transformation and regeneration, because people sense the value of continuity. The other aspect, rationality, is just practical — why start something from the beginning when you can use existing structures? Usually, if planned in a smart way, transformation should not be more expensive than a new building, especially considering the high prices nowadays.

If we zoom out a bit and look at the city as a project, you will see that it is in constant transformation and regeneration. The older the city is, the more layers of different generations there are, the more moving and touching it is for everybody. These processes are universal and natural.

Change is often difficult. For example, a lot of Rigans wish to make the city more people-friendly — with walkable streets, more bike lanes, and more greenery in our public spaces. But just as many are pushing back on these initiatives, worrying about traffic jams. Why are streets important to the city?

Riga and Vilnius have deep urban roots as they are both built in a human-oriented European tradition. Streets played a very important role in the city life as they were main public spaces — places to meet, to entertain, to trade, to shop, to move. However, during the Soviet period this tradition was completely erased. In most cities, this unfortunate period, combined with modernism, took down the concept of street life layer by layer. Now, we mostly see the street as a transitional space — it is a space which gets you to your destination, but is not the destination itself. The Soviet era streets are too wide to see the person on the other side, too plain to be interesting, too dark, as the light is directed to the driving zone, not to the pedestrian zone, uncomfortable for pedestrians, but great for driving fast, and have no commercial spaces on the ground floor. In general, they are unwelcoming to be on. Street life has been destroyed and it seems that we have forgotten that street life can be beautiful and fulfilling. The pandemic came and made us realise that we can use streets in our daily lives, but they should change and be humanised.

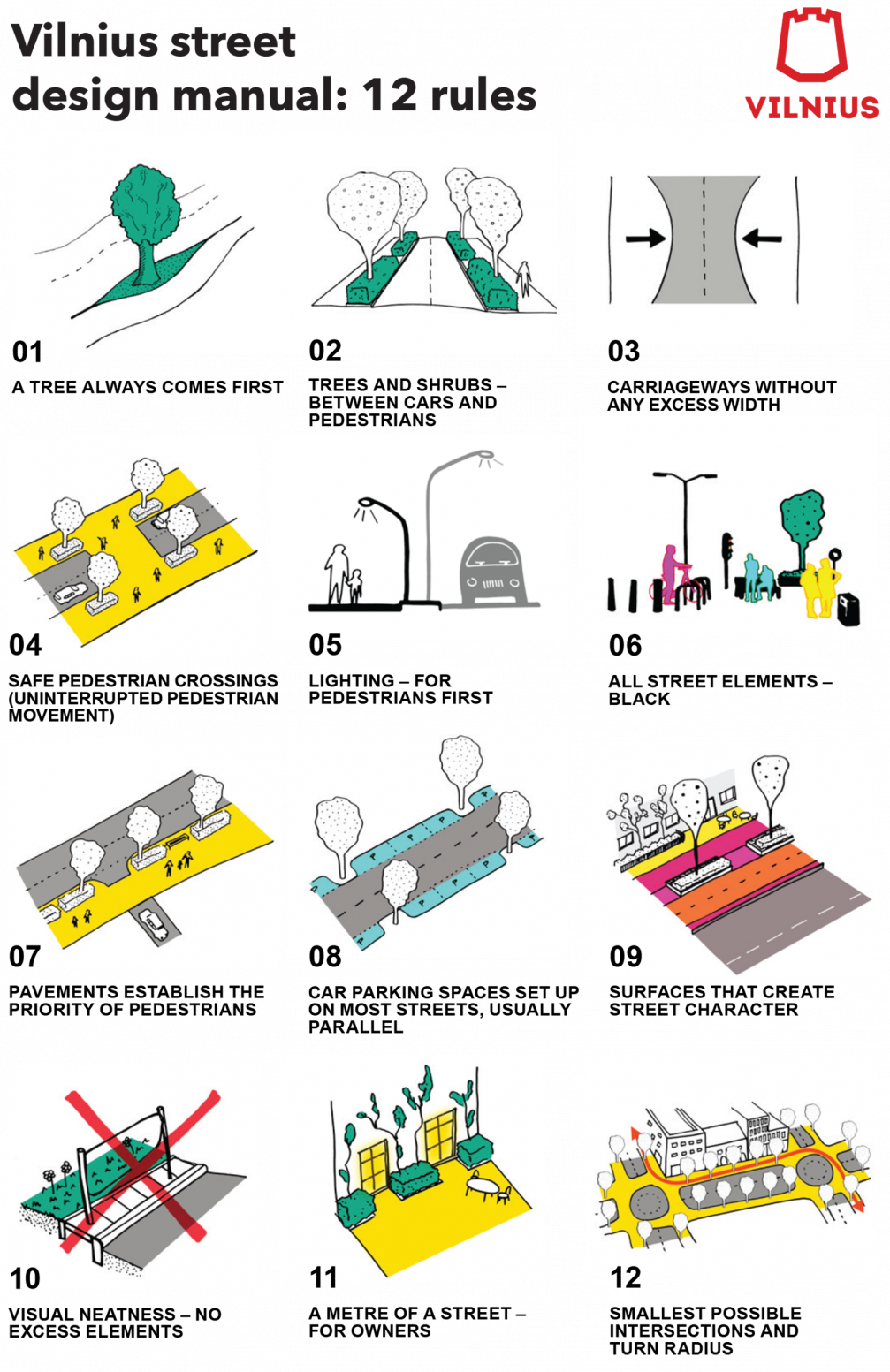

DO Architects recently completed work on the Vilnius Street Design Manual, the first compilation of its kind in the Baltics. Can you tell us about the process of making it?

Vilnius is constantly investing a lot into bicycle routes and greenery, and the Vilnius Street Design Manual came to life because we need street life. I think a great step was making Vilnius into one big outdoor café just after the first wave of the pandemic. It made the city unbelievably alive. Another step was our Naugardukas Street-Park pilot project where we applied all the principles described in the Vilnius Street Design Manual. After these projects there was a need to conclude them, to make rules that every street should reflect human-oriented values. With a team from five different fields — architecture (DO Architects), urban planning (MMAP), landscape architecture (Gyvas miestas), lighting (Vilniaus apsvietimas), and the municipality — we created the manual mostly for the transformations of Vilnius’ Soviet-era streets into inspiring modern humanised streets.

How did you determine the key principles?

As you can imagine, the task of changing the whole city’s streets is enormous. The information load is too big to do it all at once, so in the process we understood that we have to «eat this elephant» piece by piece. We understood that we must define core values and priorities which reflect current needs. These twelve principles are not permanent, over time they will change and be replaced by other solutions relevant to the problematics of that time.

For example, two years ago, there was a big problem with old trees — they were constantly being cut down. So the first principle of the manual — «The tree always comes first» — gives you a value with which you have to think creatively. In every situation you have to think about how to save and integrate the tree — maybe you will curve the pavement, maybe you will gently move the building line, maybe you will think of a new function around it.

Other principles like «Lighting for pedestrian first» and «All street elements – black» are new rules that change the Soviet approach. We want to inspire people to use the street, so it must be light and pleasant. It is also an aesthetic shift. Lighting posts and litter bins are black or dark green in western Europe to resemble tree trunks while in post-Soviet areas they are zinced. We wanted the Western European tradition and rhythm.

The manual is easy to read and to understand. Is it just a pleasant coincidence or was it important for you?

Thank you for saying that, it was very important to us! The manual should be understandable to everyone — to engineers, to citizens, to developers, to inspectors. We wanted to create a do-it-yourself book rather than an official document nobody really uses. There are actually two Vilnius Street Design Manuals — the short one is 12-pages-long, and the main principles can fit on a postcard — for explaining the core values. The other is a 600-pages-long manual with more detailed information. I strongly believe that one of our tasks as architects and urbanists is to make complex urban concepts understandable for a much greater number of people.

The manual is quite new. Has it produced any results already?

Currently, I think, almost 20–30 streets are being humanised according to the manual. People say that they feel like they are in Amsterdam. I tell them that it is just Vilnius they have never seen before!

Quality of public architecture and public spaces is a topical issue in Latvia. Tell us about the situation in Lithuania! What determines the quality of public architecture?

Public architecture should reflect the values of the country, its priorities. In the perfect scenario, public architecture should inspire and educate us, set the tone for the way of life. For me, the best example is Nordic countries with their warmth and openness in educational buildings and public spaces.

In Lithuania, on the one hand, we are building new exceptional quality public buildings and public spaces which really elevate and educate us, like the Vilnius University Library Scholarly Communication and Information Centre (Paleko Arch Studija), and Vilkaviškis City Bus Station (Balčytis Studija). On the other hand, we are still struggling with Soviet inheritance as we renovate it without radical positive transformation. In Latvia, I see a similar situation — new high quality architecture and quite poor quality Soviet building renovations instead of elevated transformations.

The most common misconception is to think that changing public buildings and public spaces for the better is financially expensive. We had an enormous amount of EU funds, and what did we do with it? We insulated Soviet-era buildings and changed the asphalt of Soviet-built streets. We did not transform their essence.

Often small efforts and a human-centered attitude make the biggest change. It could be a small gate in a fence to create a new pedestrian route or transparent ground floor windows without those matt stickers which create a human connection. It could be just lights lit in windows and doorways as if to say «this building is welcoming you».

Recently, you came to Latvia to speak at the Baltic Wood Building Forum. One of the projects you presented was the Pelėdžiukas (Little Owl) kindergarten near Vilnius. Tell us about the project!

This is the first kindergarten renewal project in Lithuania in which the renovation of the building completely changes the values programmed in the architecture. We say it’s the first because all previous renovations were focused on the beautification and renewal of what was there, but not on questioning the existing spatial plan. We completely transformed outdated and even toxic routines by restructuring the spatial layout.

Pelėdžiukas was a typical Soviet-era kindergarten, created with minimal public spaces in order to limit collaboration and natural human engagement. Dark corridors are obviously not inviting to meet, talk and play while making friends. To highlight the significant change in the philosophy of the kindergarten we chose wood as building material. We wanted to emphasize a warm welcome which stands in contrast with the Soviet apartment blocks and uninspiring parking lots. On the scale of the small city it has a huge impact and works as a social sign – wooden walls, wooden roof, warm light, and kids all around inspire joy.

Three wooden extensions that form a closed courtyard were added to the kindergarten. Children start their day by entering the courtyard which is always busy and bustling as it is surrounded by public spaces — the library, the living room, the concert hall, the canteen, and the roof terrace. Once inside, the children, teachers, and staff feel like at home — a variety of spaces allow them to choose different routines every day, and that by itself is a form of natural education and personal development. Each classroom incorporates a playroom with a sloped roof, where children can observe the ever-changing light falling through skylights. There are no backdoor rooms as well as no backdoor staff. The cleaners room is under the stairs with a glass window and door, so that the kids would know the person, see what tools they need and what they do. In the dining room, a big window opens into the kitchen, allowing the children to observe and interact with the cooks while they are preparing food. The cooks have now become the stars of the kindergarten.

At the forum, you mentioned that, in Lithuania, there are strict rules for timber structures. It is the same here in Latvia. What challenges did this present to you in the kindergarten project?

In my opinion, fire safety requirements in Lithuania are far too strict. If treated well, wood can be as good at fire-stopping as any other material. We had to cleverly come up with many creative ways to use wood in the kindergarten project. We used it in the construction, the facades, and the interior. The constructions are wooden but covered with plasterboard, and I really hope that in a few years it will be possible to remove the plaster when the regulations change. To use wood for the facades, we had to create more fire compartments than for any other material. We couldn’t use wood finishes in the interior due to flammability, so we got around this creatively by using integrated wooden furniture as it is not regulated.

However, the point is that maximum safety is required, and this should be ensured smartly. These laws contradict tglobal environmental issues. As wood is a renewable resource and it should be used more instead of artificial non-renewable materials.

We are very grateful to the team of Vilnius district municipality who believed in wooden architecture and to the director of the kindergarten for actually running the place in a new way. It is a great step toward big changes and contemporary public architecture.

Recently, you initiated a new project to help rebuild Ukraine. How did this project start and how will it work?

Rebuild Wonderful Ukraine is an idea to unite Central and Eastern European architects, lawyers, philosophers, and donors with Ukrainian institutions, and to share our experience about positive transformations of soviet inheritance. We invite everybody to join!

Ukraine must see our wins and mistakes — that we renovated soviet blocks instead of re-charging them with new living scenarios. Good architecture has incredibly positive effects on humanising and de-sovietising cities. We started with an online event in Vilnius and in Ukrainian cities. Now we are making an online collection of good transformations, with explanations and ready-to-use projects, as our kindergarten, for example.

People often don’t understand the importance of the space they live in and its huge influence on their everyday life and choices. When we talk with institutions and authorities, this aspect is overlooked too often, because the priorities are good insulation and energy efficiency, things you can easily measure. But what if we could change the default to cosy, practical, and inspiring places, which bring people together? Architecture is code — we program how people will use the space and how they will feel there. The soviets understood it too well, and programmed cities as non-social, without natural human touch, without a sense of belonging. So I feel that we understand Ukrainians and have a chance to make it better this time.

Viedokļi