The urban environment of Riga has lately been seeing a new kind of change and activity. Last spring, the old medical vehicle depot between Miera and Brīvības Streets was reshaped into the Tallinas Street Creative Quarter: the most popular, accessible and mainstream project of the organisation Free Riga. Free Riga has been repurposing vacant buildings placed in its care since 2014, but five years is, at the city scale, hardly more than a first step.

Since the restoration of the independence of Latvia, the population of Riga has shrunk by more than a quarter.1 During the Soviet industrialisation, Riga grew both spatially and in terms of population, but the end of occupation brought about a rapid emigration of non-Latvians. Denationalisation placed many buildings in the hands of people who lacked the resources and experience to manage their newly acquired estate. Joining the European Union further opened the doors for emigration to the West, which only grew after the 2008 financial crisis. The bursting of the real estate bubble caused the suspension and abandonment of many construction projects. There are very few immigrants in Latvia, and the demographic situation has been deteriorating since 1990. As a result, many buildings in the centre of the capital stand vacant. According to Mārcis Rubenis, one of the founders of Free Riga, there are between 500 and 1000 abandoned buildings there. Often these are buildings with historical value that play a key role in the structure, environment and identity of the city.

Latvia is, of course, not unique in this respect ― there are about 11 million vacant buildings in the European Union.2 The fluctuations of real estate markets and the emergence of gaps in the urban fabric are an integral part of late capitalism. Periods of growth create new spaces that are abandoned with the onset of an economic downturn. This process is intensified by globalisation, technological innovation and political changes, which make the over-production of space inevitable.

In a sense, urban development creates a periodic emptying out of buildings. Centralised urban planning slows down the influx of investment and encourages owners and developers to wait out the planned changes. Residential buildings in the suburbs hollow out the city centres and small businesses cannot compete with the shopping malls in the outskirts. Climate change and the waves of migration associated with it will only accelerate spatial fluctuations in urban environments and the mismatch between the supply and demand of space. The problem of vacant buildings is here to stay.

Temporary urbanism

Temporary use of space has gained popularity across Europe, and now, owing to the efforts of Free Riga, also in Riga. The first impulse to open up abandoned buildings to the public came with the art centre Totaldobže that occupied the vacant factory buildings of VEF and repurposed them for workshops, exhibitions, artist residencies and cultural venues. As Totaldobže left VEF in 2014, the movement Occupy Me, portraying Riga as the capital of empty buildings, was created in response to Riga’s status as the European Capital of Culture. By placing the yellow Occupy Me stickers on abandoned buildings across Riga, activists illuminated the paradoxical situation where, despite many unoccupied houses, cultural initiatives were lacking the space to realise their efforts. The campaign created a need to map the vacant buildings, and Free Riga was born.

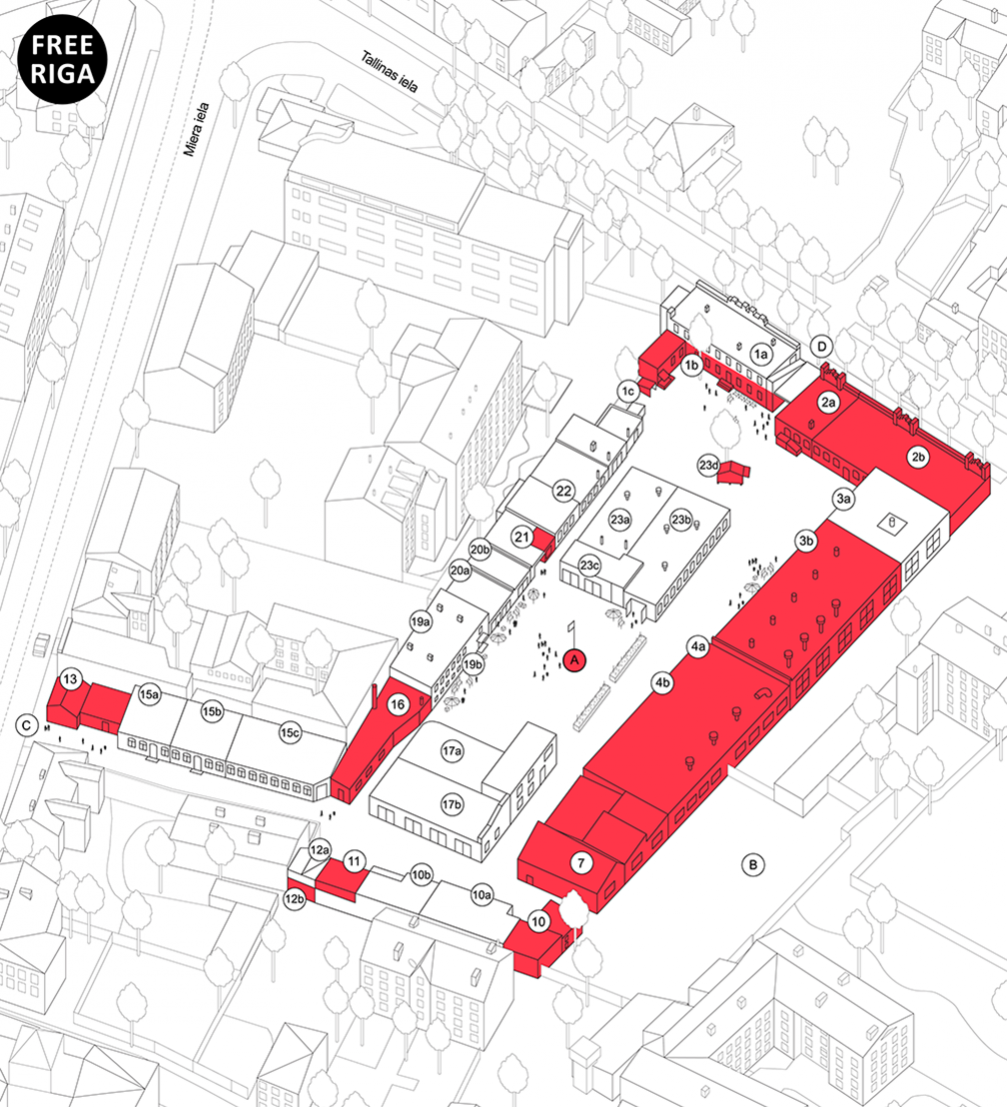

Until 2017, Free Riga occupied buildings in Līksnas Street, as well as the Zunda Garden and the former tractor factory hangar there. Until very recently, 27 Dzirnavu Street also hosted an artist residency centre D27, which not only accommodated artists, but organised cultural events, opened an exhibition space and a free-shop, created an open-air stage and a communal garden. Currently Free Riga has four buildings in the district of Lastādija: these are occupied by artists, artisans, NGO’s and local activists. Finally, the Tallinas Street Creative Quarter is thus far the most ambitious project of Free Riga ―the industrial territory of more than 4 thousand square meters is now home to the concert hall Tu Jau Zini Kur, several bars, the sound studio Gas Sound Studio, exhibition spaces and workshops. Unlike in Lastādija, where Free Riga spaces serve as a local cultural centre, Tallinas Street Creative Quarter aims to be a creative centre for the entire city with its size, central location and commercial activities.

The key function of Free Riga is to mediate between the owners of real estate and its temporary users, identifying the commonalities in their interests. The owners are attracted by the 90% tax credit provided by the public benefit status of Free Rig», while residents pay minimal rent. Other residents of Riga also gain from the cultural activities hosted during a building’s temporary use. Free Riga mediates between all stakeholders, providing a bridge between economic interests and creativity, between formal and informal cultures. Agreements are made for short periods of time and then extended, agreeing on additional conditions that become necessary during the temporary use of space. Residents, on the other hand, agree to invest their time and energy into the revitalisation and repair of the building.

Free Riga takes part in Refill — the network of European cities (also known under the title «Reuse of vacant spaces as driving Force for Innovation on Local Level») that popularises temporary urbanism and receives support from the European Regional Development Fund. Some of the activities of Free Riga residents are funded by the State Cultural Capital Foundation of Latvia, and a cooperation with the Riga City Council is slowly being formed, yet the society at large ― still not quite ready even for bike lanes ― is slow to embrace the idea of temporary urbanism. Riga simply does not share the experience of Western cities with a longer tradition of solidarity, squatting, and community involvement. In Paris, for instance, 62 temporary urbanism projects have been completed since 2012, including revitalisation and adaptation initiatives for land owned by French Railways. Closer to home, examples of temporary urbanism are found in the Užupis quarter in Vilnius and the Telliskivi creative centre in Tallinn.

Informal spatial planning in all of its forms (participatory urbanism, pop-up projects, guerrilla urbanism, temporary use, and DIY urbanism) has become a kind of trend over the past decade, garnering the attention and recognition of municipalities and academics alike. Activists, members of the creative industries and urban planning organisations (e.g. London Assembly and Meanwhile Foundation) present the temporary use of buildings as a progressive tactic that creates new models for development and the experience of space while reinforcing community involvement outside of the institutional urban development frame. Temporary use also promotes desirable social processes like solidarity, diversity, and inclusion; it encourages the communal sharing of resources and the reuse of materials. Vacant buildings present a burden to both their owners and the city at large through visual pollution, increased crime levels and reduced economic value for the neighbourhood. By supporting the use of vacant buildings, added value and meaning is created for places that lack an identity, while also indirectly boosting commercial activity in the neighbourhood. Totaldobže, for instance, provided a significant boost in the development of VEF and its surroundings, and the Tallinas Street quarter is already used in advertisements by developers, selling EUR 2000/m2 apartments nearby.

Is gentrification inevitable?

It is fitting to address the controversial concept of gentrification here.3 A change of social class is seen in all districts that have experienced a sudden influx of creative industries ― around the Spīķeri Quarter, Andrejsala, Miera Street and the Kalnciema Quarter. Artists and artisans have long since been a key driving force for gentrification, improving the image of degraded neighbourhoods as they settle them, drawn in by affordable rent. The shift in public image eventually changes the population make-up.

The leaders of Free Riga engage with the problem of gentrification; this summer, they hosted the public discussion «Gentrification: good or bad?» with Aalto University researcher Johanna Lilius outlining the positive and negative characteristics of the process. Although the discussion did not yield a definitive answer to the question posed, the participants agreed that a type of urban regeneration that keeps a given neighbourhood accessible to its original inhabitants is more desirable than the typical process of gentrification.

Jāzeps Bikše, one of the leaders of Free Riga, describes the ideal long-term development scenario as one where the temporary users of vacant buildings would become permanent residents, but this model is inherently contradictory ― as the public image and value of the abandoned territory improves, building owners are both able and willing to increase rental fees, as was the case with the owners of the space that the Totaldobže art centre used to occupy.

The effects of gentrification should not, of course, be blamed on either activists of the creative fields or real estate owners that follow the logic of the free market; a balanced urban development is the responsibility of municipal governments. Throughout Europe, the effects of gentrification are often mitigated by including accessible housing in urban regeneration projects, yet the involvement of the Riga City Council in the temporary use of vacant buildings and the creation of accessible living spaces remains minimal. Jāzeps Bikše says: «All Free Riga buildings are privately owned. Around 90 % of the vacant buildings in the centre of Riga are in private hands. Elsewhere in Europe, municipalities would buy up the vacant buildings and hand them over to temporary users ― killing two birds with one stone.»

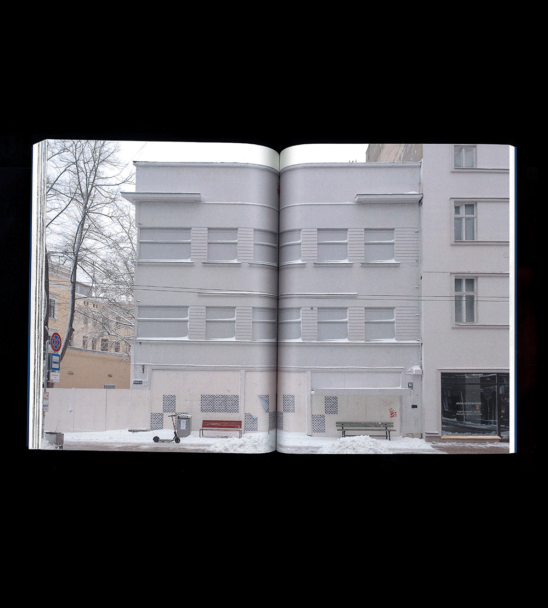

In 2014, an unfortunate situation developed around a building on 10 Tallinas Street, then owned by the City Council. Negotiations were in progress at the Council’s Property Department, with countless creative industry groups and NGO’s voicing their willingness to use the premises. The City Council decided to sell the property to somebody else, and now the over 500 m2-sized premises are rented out for EUR 9/m2 ― incomparable to the much smaller fees currently paid by temporary users in the neighbouring Tallinas Street quarter. The owner of the buildings on Tallinas Street approached Free Riga on his own initiative. For now, a three-year premise use agreement has been signed, with long-term management of the space as the aim ― this is likely to become reality, since this project is considerably more commercial than other Free Riga activities in the vacant buildings of the city.

Oļegs Burovs, director of the Riga City Council Property Department, gives the hazardous condition of the premises as one of the reasons for the sale of the building on 10 Tallinas Street. Without considerable financial investment, it is difficult to achieve the regulatory compliance required for public buildings that have been abandoned for years. Legally changing the intended use of premises presents further complications, sometimes requiring separate approval for each public event. Positive examples can be found in other European countries, where more relaxed bureaucratic standards are applied to the temporary use of empty buildings, administering regulations that ensure the safety of the public while making vacant spaces more accessible to temporary initiatives. The Riga City Council could make the process of premise acquisition considerably easier by mapping and compiling information about abandoned buildings and territories.

Mediation between stakeholders

Real estate owners do adapt to change and embrace the idea of placing buildings in the hands of temporary users, albeit slowly. Building owners and the artists who wish to inhabit their buildings often have a hard time getting along, since members of both groups typically hail from very different social and economic backgrounds. This is why the role of «Free Riga» as a mediator, building bridges between all stakeholders, is so important.

The main risk in this process of aligning interests is prioritising of owners’ needs over those of temporary users, subjecting the latter to insecurity, risk and precarity during their residence in the vacant buildings. Property guardian agencies in London (e.g. Camelot or Guardians of London) have already been criticised for their use of the pop-up format to offer extremely short-term residence agreements. This promotes a view that unstable and unpredictable conditions are the norm of city life among young city-dwellers who cannot afford renting at the market price. The positive image of the creative industries helps divert attention from the lack of affordable premises in the city centre, and morphs temporary residence into a cultural trend ― a style choice rather than a necessity. Free Riga combats this issue by involving lawyers to draw up agreements that provide as much security as possible to both parties. Even so, the agreement between Free Riga and the owner of 27 Dzirnavu Street had to be redrawn five times over the course of less than two years, and, as of November, the residents of D27 must resettle elsewhere.

The main problem of the Riga city centre ― the vacant buildings ― can become its own solution, but this can bring problems of its own, like any city-wide process. Fortunately, Riga has the opportunity to learn from the mistakes made by guardians of vacant buildings elsewhere in Europe.

This article was created with the help of Nameda Zemīte and Jāzeps Bikše from the Free Riga organisation.

Viedokļi