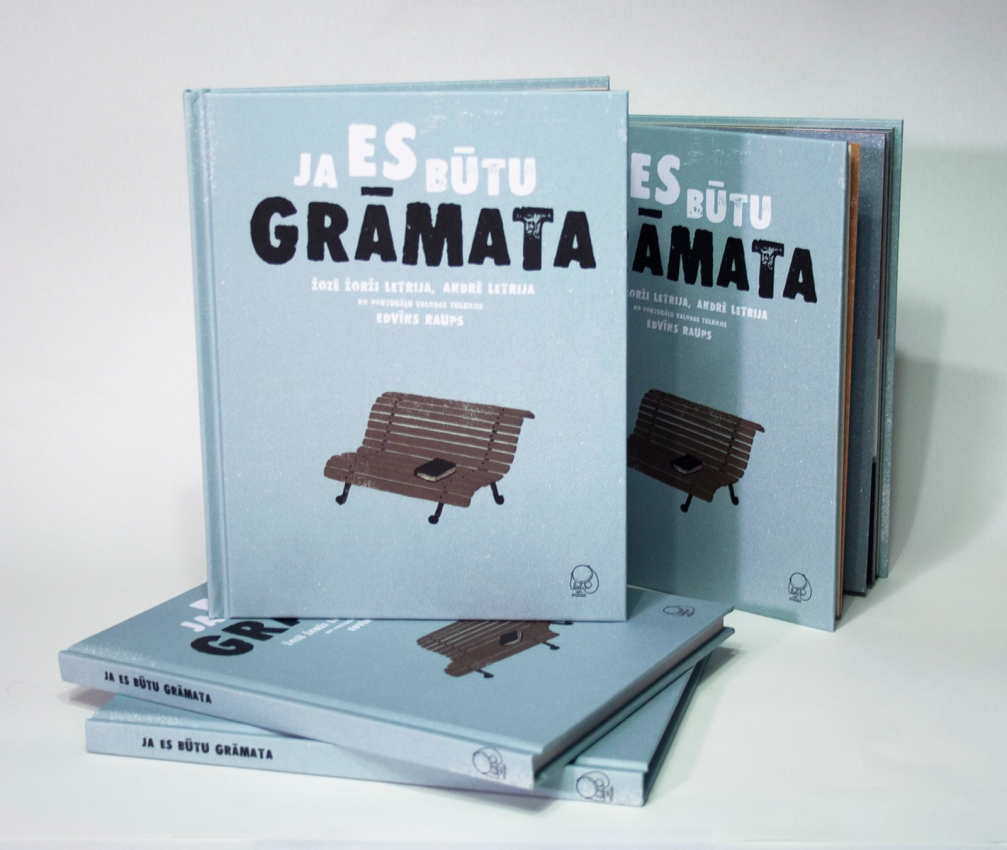

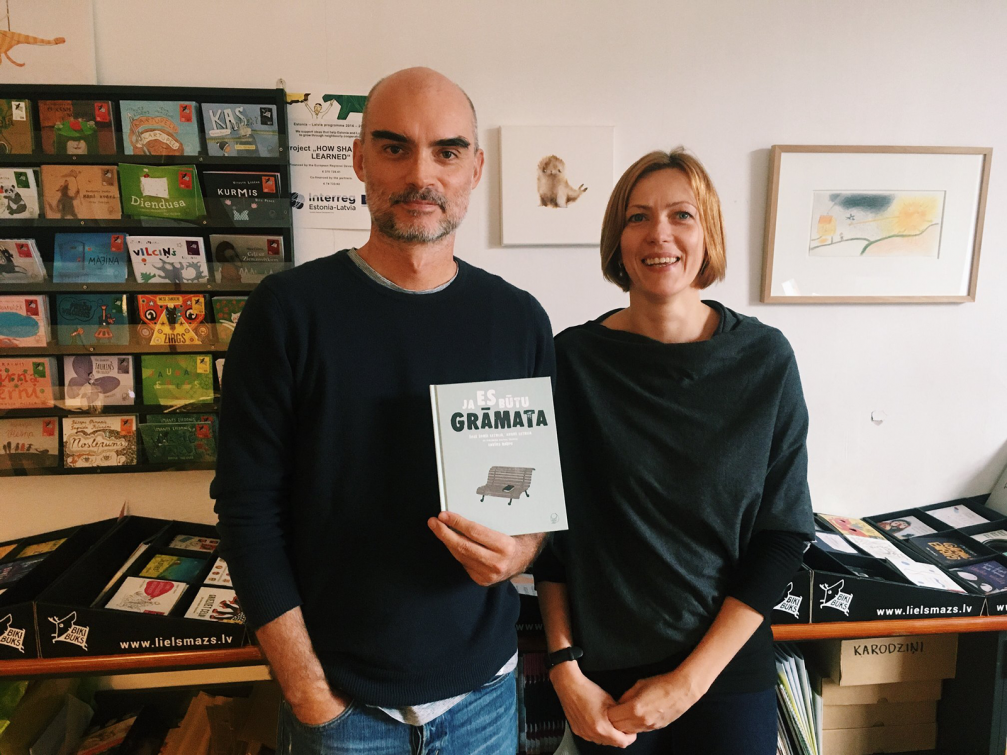

André Letria is a Portuguese author, illustrator and founder of the publishing house of children’s books «Pato Lógico». His books are internationally recognized and have received several prestigious awards, including the highly coveted mention by the Bologna Book Fair. «If I Were a Book», a thoughtful and poetic picture book on the joys of reading for all ages was published also in Latvian in 2017 by «Liels un Mazs». This autumn, Letria visited Riga to organize creative workshops and he also gave a lecture at the Art Academy of Latvia.

Your lecture at the Art Academy gave the impression that your career has been very well structured, every step so conscious and logical. Which was the exact moment when you understood that you wanted to be an illustrator?

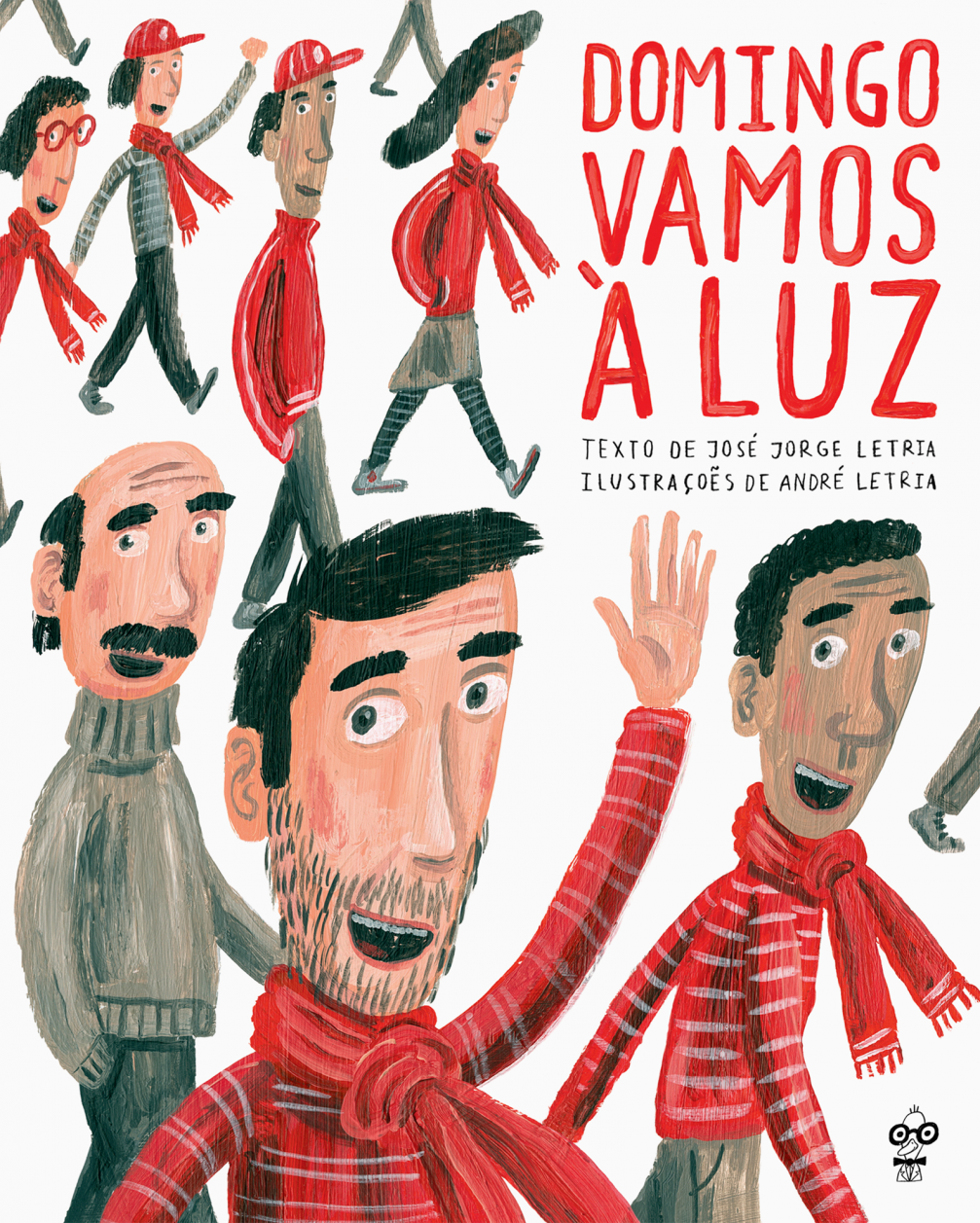

The structured image that I probably gave in the lecture wasn’t as real as it may seem. Many aspects of my career happened just by chance. I was going to college, studying painting and didn’t really know what I was doing there. At that time I had a graphic function in an old cultural newspaper, doing simple things, like making the layout. After some time, they asked me to illustrate some unpublished stories by Portuguese authors, and at this point, I started to understand what the illustration could be. Then my father (José Jorge Letria — ed.) who is a writer who worked also on that newspaper as a journalist suggested my name to some town hall project that was publishing a book. That was my first experience in book illustration and it was somehow traumatizing because it was a scale I have never tried before, making the illustrations with the need to be coherent, preoccupation about organizing everything as a whole, it took me a lot of time, I got delayed, but I understood that it could be an occupation for me.

What software did you use at that time in the magazine?

It was the beginning of the 90s, and we used no software at all. This was a very small cultural newspaper, technologically delayed in comparison to other ones. We had these big sheets of paper which worked as a scale, we used the calculating machine to count the number of letters, the size of the text on the page, how many lines, number of columns, then we made the sketches for the photos — we did everything by hand. This experience makes me feel older than I am, but it was a good school and gave me ideas on how things should be done also for books.

During the 26 years that you work as an illustrator, has the children’s literature and illustration scene changed in Portugal?

What concerns the text, the changes weren’t so big. The motor what pulled everything was the design and illustration. My generation started to look at what other countries were doing and what other schools of illustration were about. There was one particular event in Lisbon around 1997 — the exhibition and publication of an illustration catalogue, that was going on for several years annually and gathered together many illustrators. We began to discuss the things related to contracts with publishing houses, we started to have the idea that we can be more participative in the process, not only spare part that publisher and writers use as they want.

It is often considered that independent publishing houses pay more attention to visual aspects than literature, which is not true. In my father’s generation, the writer was considered the main artist in the process. Before the 90s, we didn’t have much of tradition in Portugal of doing picture books, where the text is not that big. We have them now.

Another thing related to this perspective of children’s books, we have much more young illustrators than we have young writers. That’s a phenomenon I cannot explain. I can name 6 or 7 writers from generation around 30–40, but if I count the illustrator’s of that age, 20 wouldn’t be enough. It frustrates me as a publisher, because we are always looking for new writers, some novelty, new ideas.

Why did you decide to establish your own publishing house?

I felt I needed to experiment. I wanted to have a total freedom in the process from the beginning till the end: to take the time I want, imagining different design and production solutions, deciding which authors to invite… Also, I was tired of being a freelancer and accepting commissions I sometimes didn’t consider brilliant. But I kept doing it also when I got the publishing house, even though it was thought to be a safe space for me to do artistic things. But at some point things started to work out, today I don’t have to accept any commissions apart from those that I like. Now the worst thing is that I don’t have much time to do illustrations myself, which is strange since the main idea why I wanted to have it. I have to work on it.

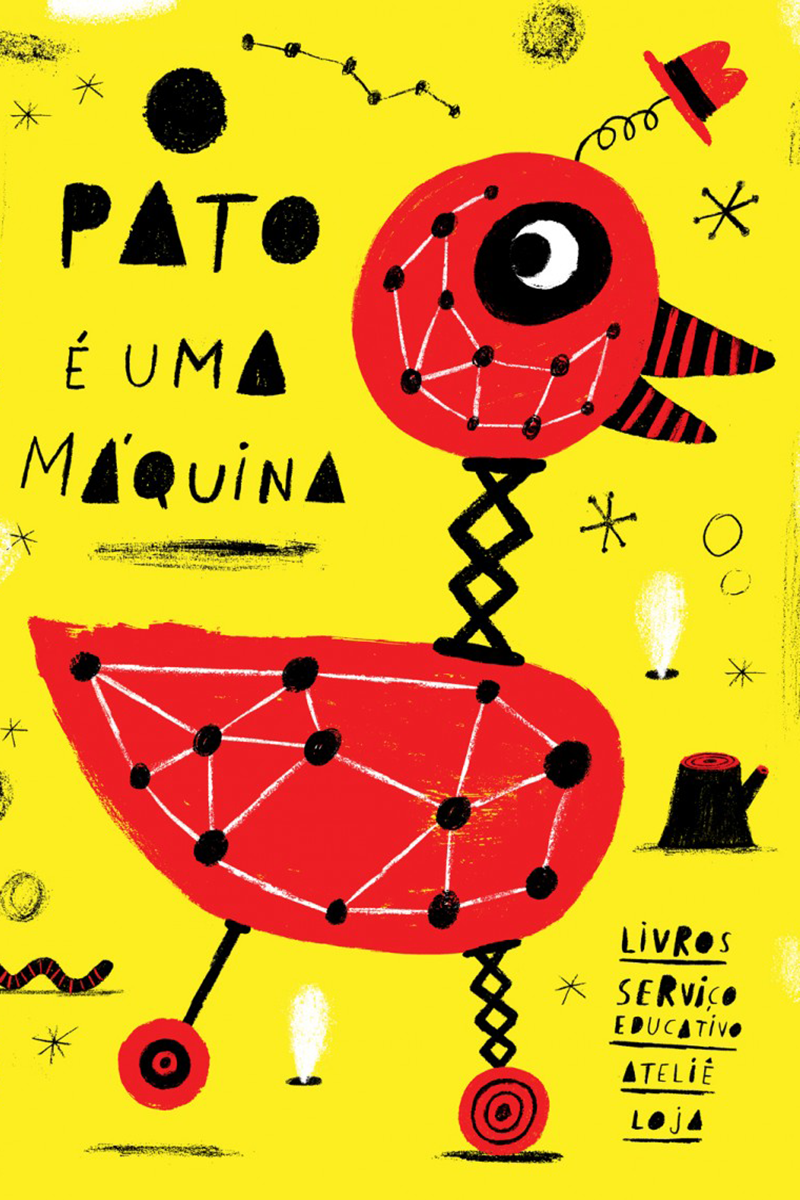

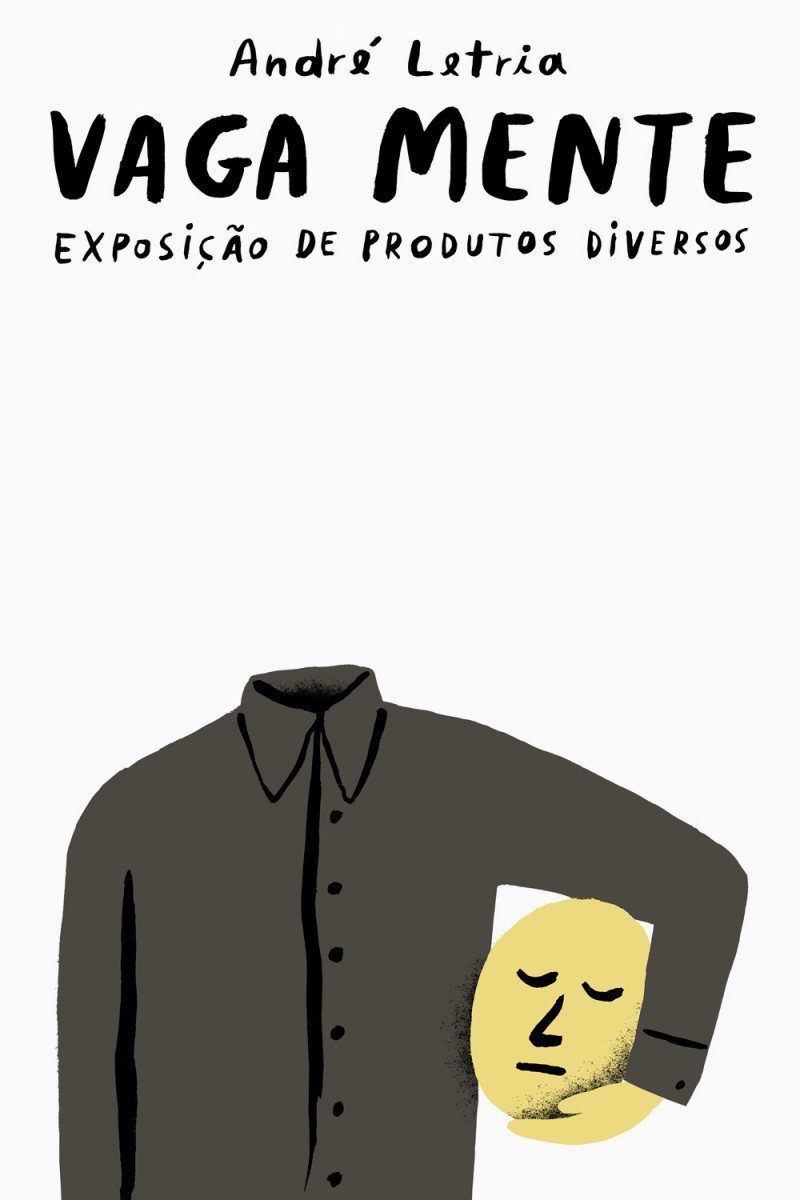

How would you describe the work of «Pato Lógico»?

At «Pato Lógico» we have three ways of working: the publishing house is the main thing we like to be, the studio is what we do for fun and need, and the educational service that gathers everything together. It can come from books that we have in our catalogue, but it is also an instrument for the studio. Sometimes we add educational service as part of a project for our clients because socially speaking it is an important part in the way working with cultural content.

If we could choose and have all the time and money we need, we would gladly be publishers only and would keep on doing 5–6 books a year, or 8 maybe. We have the idea that the books should always be done as very artisanal, non–industrial way. We like to think about the book. Sometimes the process of thinking can take two years, and then we decide that it is not ok and stop.

What are the most characteristic works of «Pato Lógico»?

One is «Images That Count» — a collection of silent books, where pictures tell the story with the minimum text possible. It was also an experiment with the power of narrative quality of images. The title having only one word gives the reader more options of interpreting the story. The other would be the collection of «Actividaries», the name of it is a mix between two words — activities and abecedary. And one more project that is not made yet, it will be explaining how the business of books work, where we interview people who are connected to the business of books — publishers, illustrators, designers, printers, book sellers, librarians, curators, — everyone that can be important to this ecosystem. And we show spaces related to their professional lives.

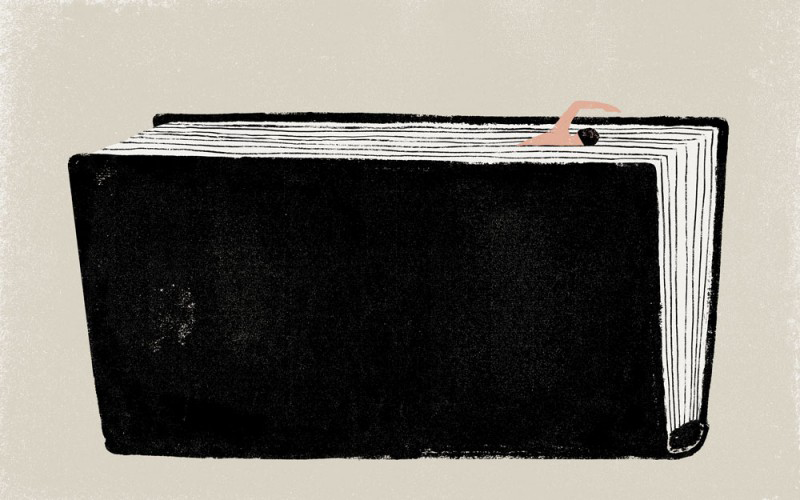

It sounds related to «If I Were a Book», that is also translated in Latvian…

This book was probably more artistic and dreamy way of thinking about it. This one is art, the other one is a theory, it’s more technical. But they both represent our special interest in books.

Do you see yourself as a Portuguese artist?

Artistically speaking, I don’t know, but in terms of content and subjects, our approach is definitely very much Portuguese. We have an interest in our history, culture and society. One of the «Actividiary» collection will be about the Portuguese revolution in 1974, for example. It is also with one–word title, and this one will be called «April» — the month when the revolution happened. We feel the mission as the publishers to have these social concerns, to show the readers that memories must not be forgotten, that they are important for understanding what we are facing in present, and also it is a political position that we stand for as publishers.

«The Sea» also has a lot of Portuguese references. The idea of doing it was because I feel a personal connection to the sea, and it is all over our history, it is the main part of our formation as a country. We made this book much bigger than we thought it will be, and it became an important instrument in our educational service. In Bogotá International Book Fair we created 200 square meters stand form this book — a path for visitors so they can dive in Portuguese sea. In this event, the book suddenly became a three–dimensional project, where people could go inside. Around 7000 people a day.

In the lecture, you said that illustration «it’s not painting and it’s not design». What is it then?

When you paint, your work is very independent, it is the beginning and the ending of the process, you have the idea for an exhibition, for a masterpiece, you work alone, even if you have references and inspiration from outside, you create your own thing. When I work as an illustrator, I don’t want to be independent, I want to work in a structure where other participants have an intervention. Illustration is part of process that has the book as the main object.

Design for me is a tool to make a good book. And this shouldn’t be considered an arena where you fight between egos or different artistic languages, where the text is something good, but illustration less important. You shouldn’t look at the book thinking the design is so good but it is imposing on the illustration. The idea is to make something that has to be seen by the reader as a whole art–piece. That’s why I think sometimes it is very important for illustrators to understand that they have to have their own voice and references, but not to be so concerned to make illustration something it doesn’t need to be.

Viedokļi