This year, there has been no shortage of events around the world that caused indignation, anger, and even protests in the streets. But what role did creative industries have in social movements and political protests? We hope that this series of articles will inspire Latvian designers and artists and will encourage them to express their views more actively, using their creative thinking and skills.

For more than a hundred years creative professionals have been visualising ideas, promoting involvement in social and political issues, and taking part in forming a collective position. By the beginning of the 20th century, protest art was defined as a creative activity of individual activists or social movements, which traditionally included forms of expression such as theatre, fine arts and graphic design. Today, the diversity of creative activities in protests is much broader, and information travels much faster. The forms of creativity vary from anonymous posters, clothing elements and attributes of a protest crowd to specially designed art, design and architectural performances. We looked at some of the most captivating examples of protest art and design from the last decades, including both physical and virtual activities.

Graphic design and illustration

When we think of protest graphics, the first thing that comes to mind are self–made posters and banners carried by the crowd, however, historically works by designers and artists have been just as important. A masterfully created image often exceeds the limits of a certain social or political activity and serves as documentation of historical processes. From the iconic portrait of the revolutionary Che Guevara and the anarchist symbol to the LGBT rainbow and the peace sign — the works of graphic designers mark the most significant protest movements of the century, and the digital age hasn’t diminished the meaning of their work in the slightest.

American artist Shepard Fairey is one of the most renowned protest graphic design authors of today. His political activities include the «Obey Giant» stickers (1989), street art campaign «Be the Revolution», as well as a series of posters for the presidential campaign of Barack Obama (2008). In 2009, Peter Schjeldahl, art critic and journalist of «The New Yorker» praised the «Hope» poster as the most efficacious American political illustration after «Uncle Sam Wants You». In January 2017, on the inauguration day of President Donald Trump, Fairey published poster series «We the People». Using the familiar aesthetic of the «Hope» posters, these works featured women of Latin–American, Muslim and African American descent to represent the most vulnerable groups of society during Trump’s presidency.

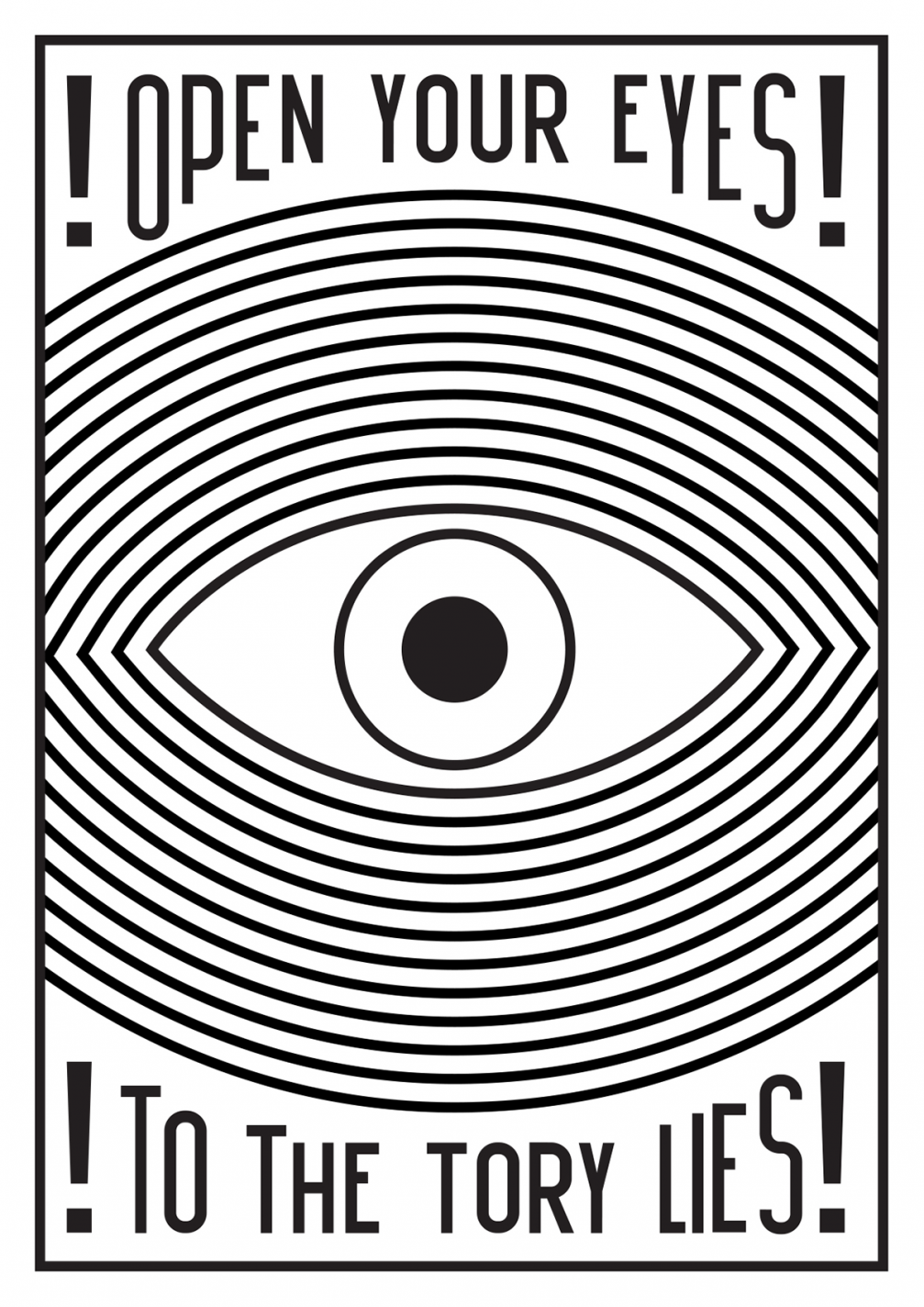

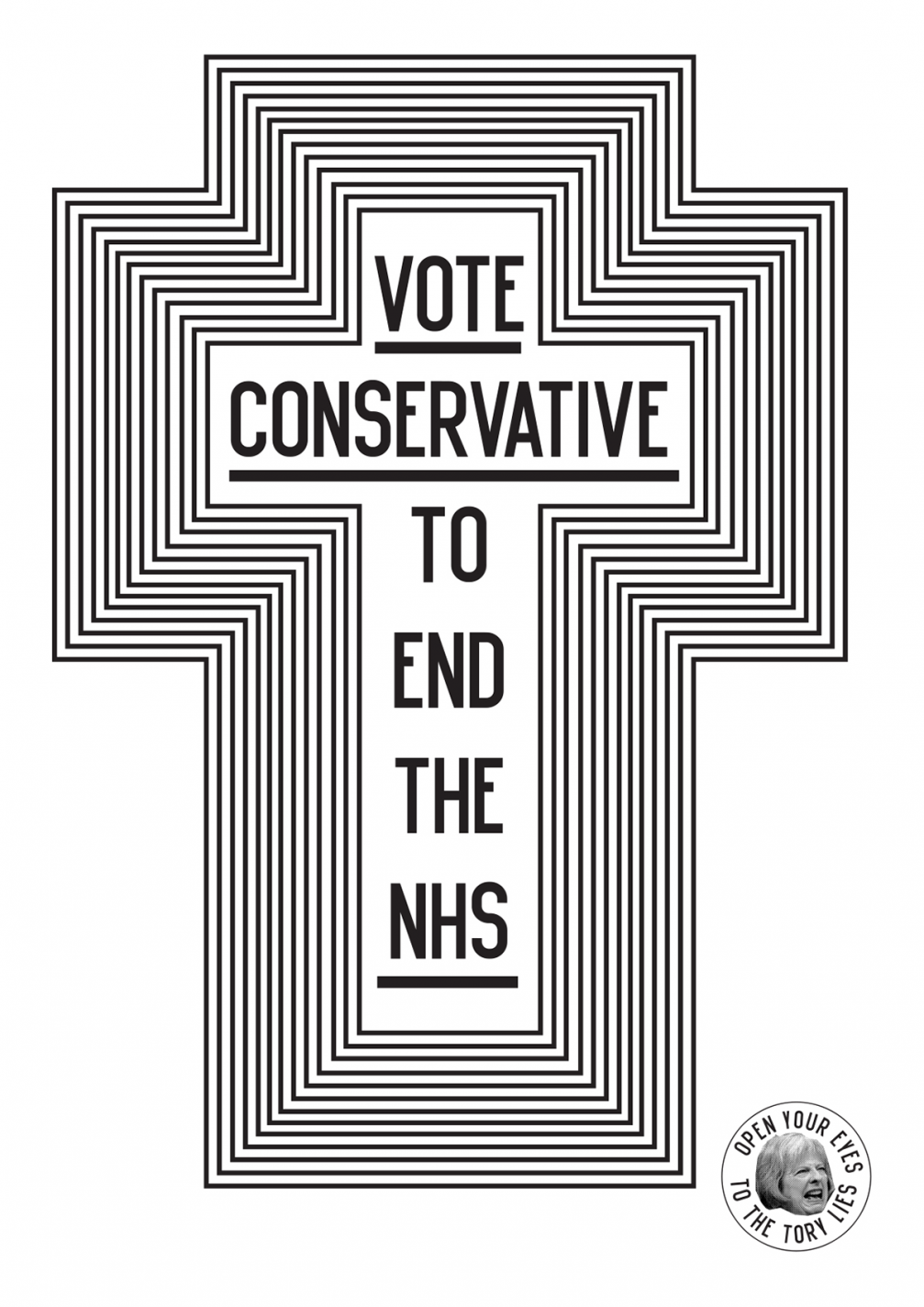

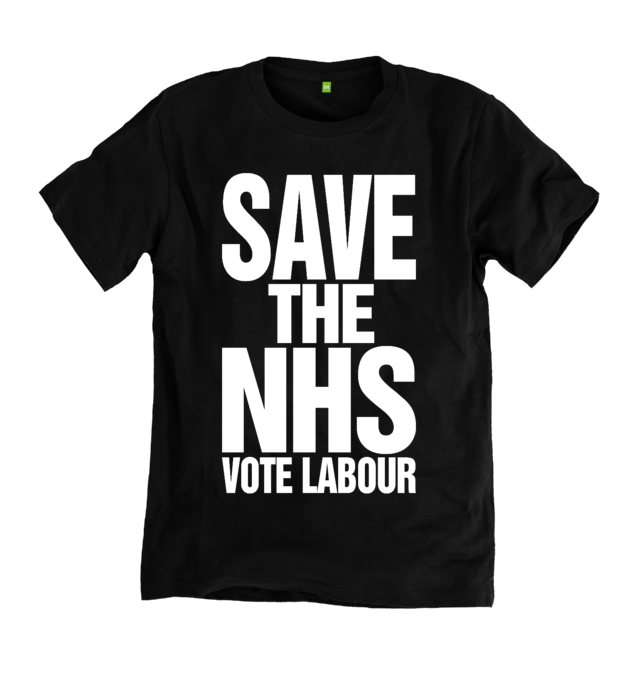

Graphic designers and artists also watched the UK’s general election in the beginning of last summer. Designer, illustrator and artist Rob Lowe, also known as Supermundane, developed a series of posters, free to download and easy to copy, that urged voters to ignore the Conservative Party’s campaign and reminded the public of civic responsibility. This initiative was based on the designer’s conviction that tangible design in public spaces could be a way to reach beyond one’s virtual bubble of communication. Shortly before the election, the British graffiti artist Banksy introduced a free souvenir — an art print for everyone who will vote against the Conservative Party. In this work, he interpreted his own graffiti «Girl with a Balloon», replacing the red balloon with a motif of the British flag.

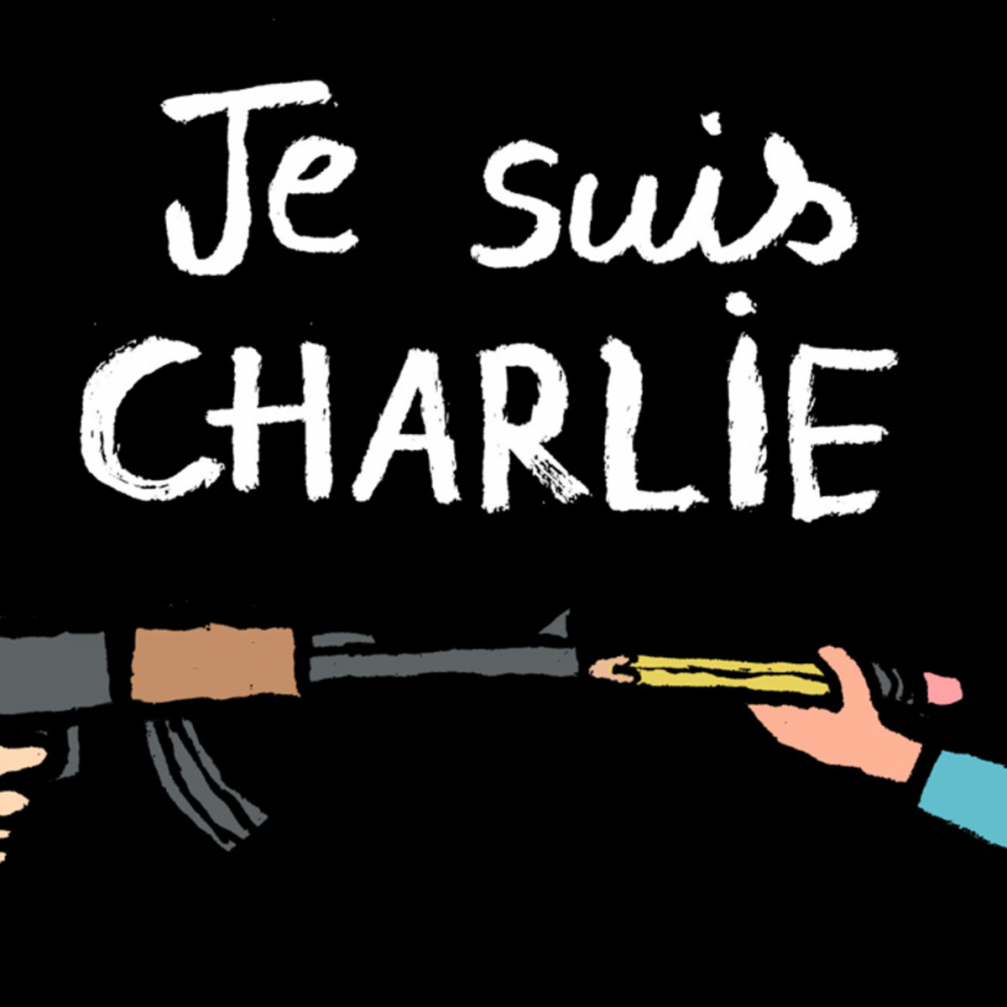

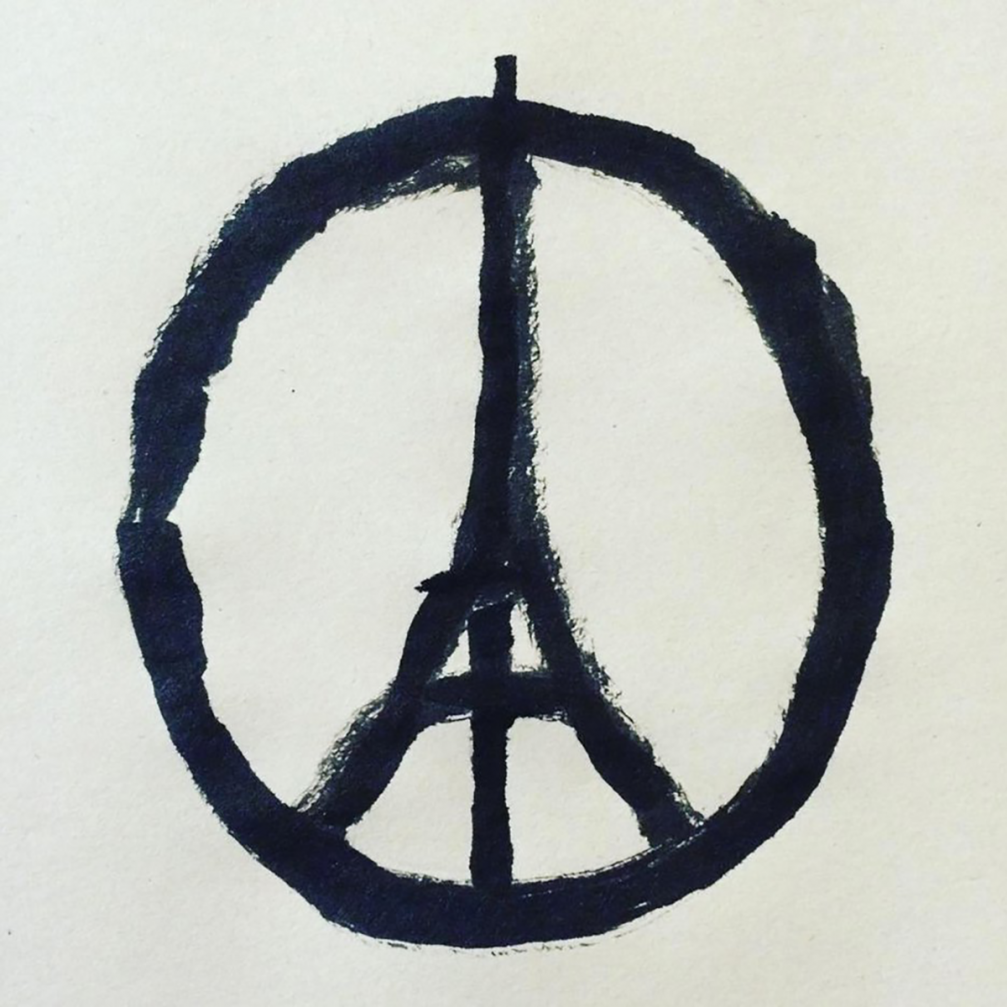

Although the genre of critical satire and political drawings has evolved since the 18th century, illustration has now become a full–fledged media reflecting social and political developments. Unlike traditional forms of visual journalism — photos and videos — it gives the viewer a much wider range of interpretations. An event that triggered a strong response from the illustrator community, was a violent attack on the office of the «Charlie Hebdo» magazine in 2015 in Paris. An assault on a satirical magazine, in which illustration is an essential part of the content, became an assault on the artist’s freedom of expression around the world. Expressing sympathy and protest, traditional and social media filled with robust and ironic drawings dedicated to the tragedy. The most famous ones are the bloody newspaper showings its middle finger by American cartoonist Dave Brown and the pencil stuck in the barrel of a gun by French illustrator Jean Jullien. The «Peace for Paris» symbol by Jean Jullien resonated just as much when several months later more terror attacks followed in Paris. With enormous speed it spread among social network users and participants of demonstrations in different parts of the world — «Peace for Paris» was drawn onto the faces of protesters, printed on posters, and projected on buildings.

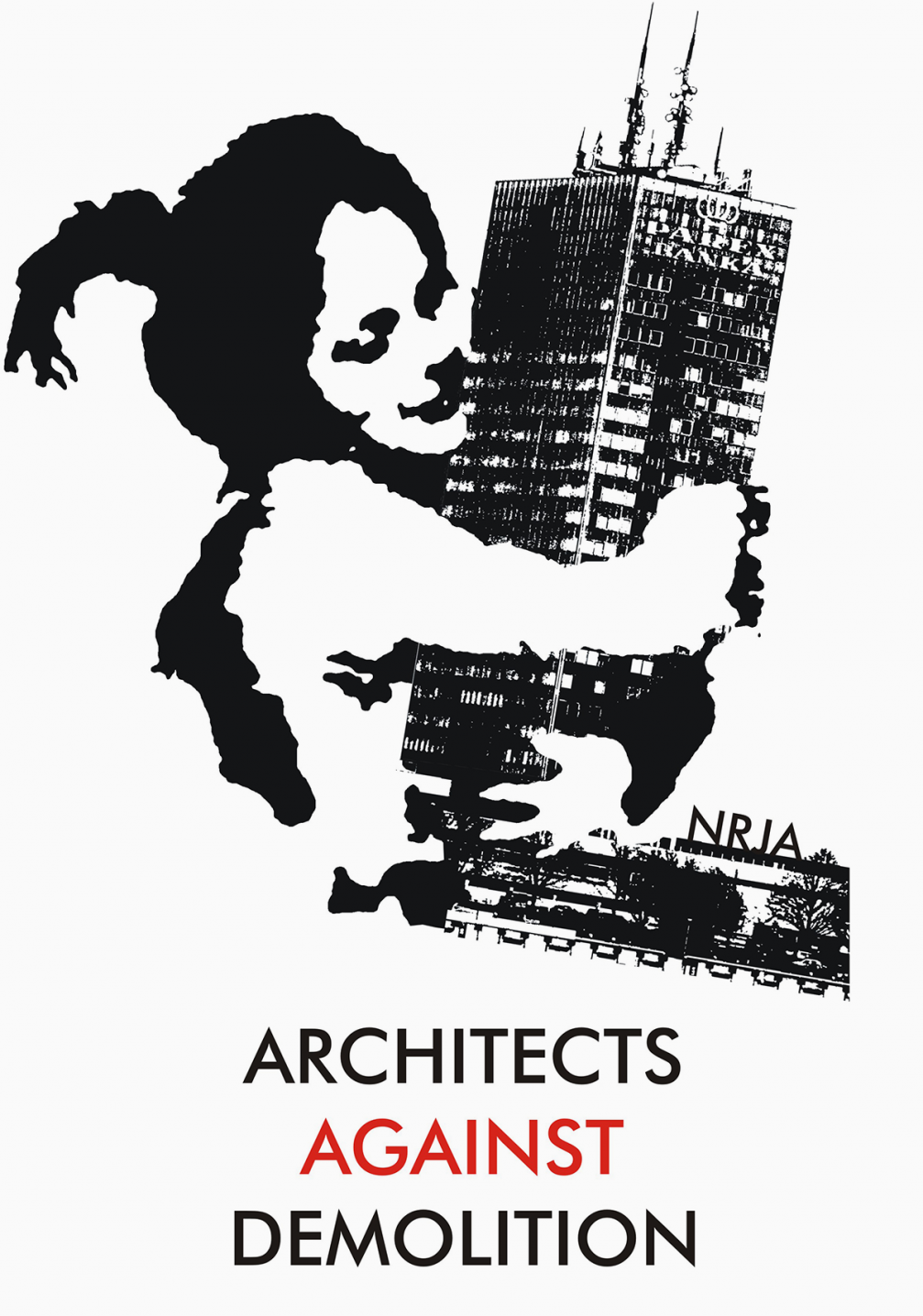

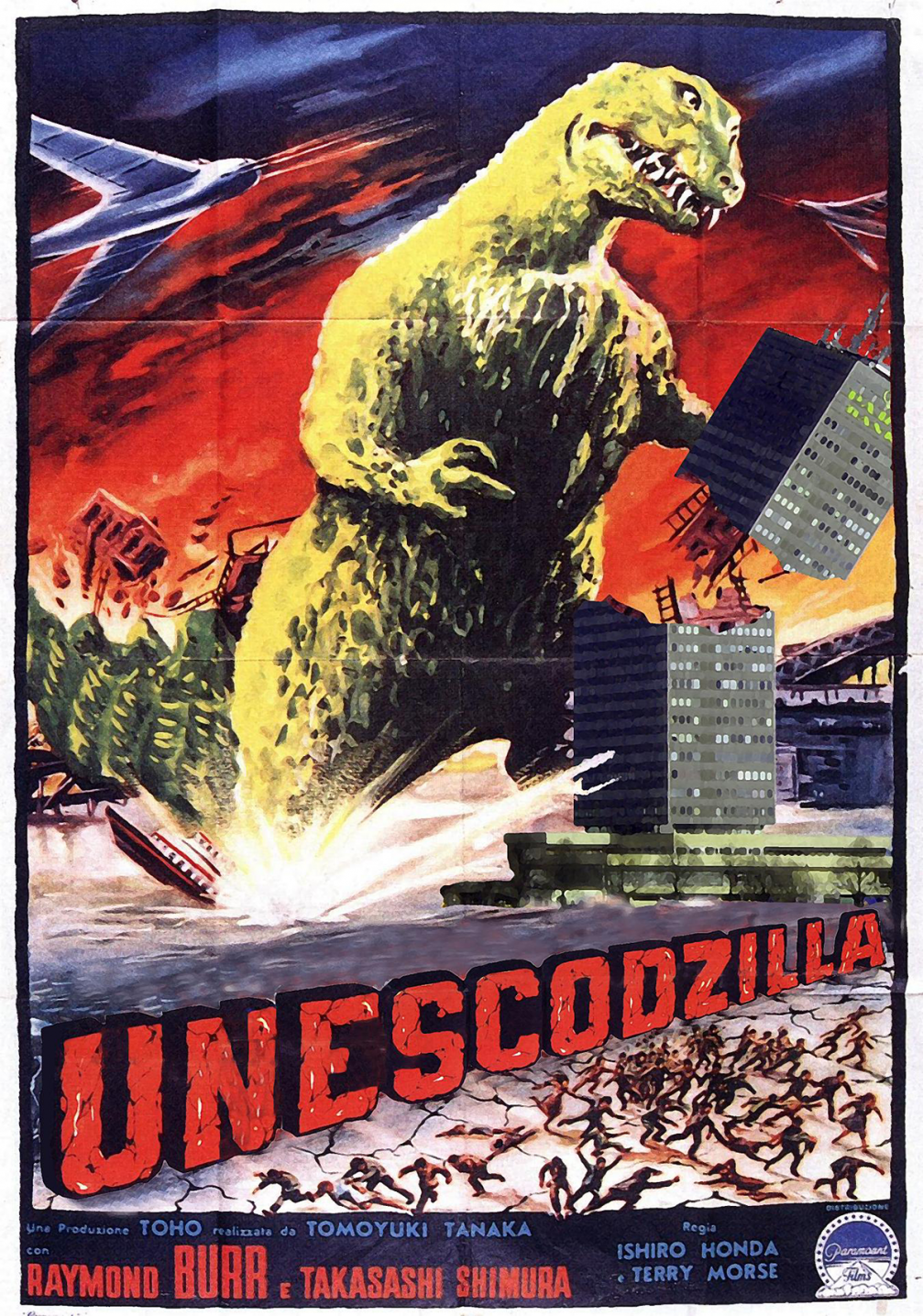

A protest campaign, which was organised by Latvian creatives and found an expression in graphic design, took place in 2006 and was a reaction to the idea of demolition of the building of the Latvian Ministry of Agriculture. Initiated by the architecture office «NRJA», it challenged UNESCO’s recommendation «to eliminate the massive and ill–suited high–rise building from the Riga Old Town panorama». The architects expressed their call to preserve heritage of modernism by interpreting iconic graphics — they developed a series of posters and T–shirts with their versions of Banksy’s girl who embraces the high–rise building and Godzilla’s film poster, renaming it «Unescodzilla». «There is no future without history. Understanding architecture and taking part in its development should be trained from the childhood,» explains Uldis Lukševics, head of «NRJA», whose active position delivered a positive outcome — the high–rise building is still in place.

In the meantime, local politicians and their characteristic expressions have become popular among street artists. The former president Vaira Vīķe–Freiberga with a crown of stars and the former Prime Ministers Valdis Dombrovskis with bear’s ears and Aigars Kalvītis with pig’s ears and snout all have graced the walls in Riga. Notorious phrases as «Nothing special» and «We will be taupīgi» by the former Minister of Finance Atis Slakteris, as well as Ingmārs Līdaka’s call «Shut your mouth!» can be read on walls, too. Some visits of foreign politicians have triggered a visual response too, for example, in 2005, the advertising agency «!Mooz» greeted Gorge W. Bush with posters calling him «Peace Duke», which was meant as a disguised insult. True, these caricatures make the viewers smile, however, they not encourage anyone to engage in an action or a deeper reflection.

Fashion design

Katharine Hamnett can be considered the first fashion designer to bring political slogans to the clothing industry. Her T-shirts, adorned with massive inscriptions, have been bringing forward issues of public life and politics for several decades. Among the most popular works by Hamnet is her T–shirt design «Choose Life» (1983), while a year later, a photograph taken of the designer in a baggy shirt and sneakers shaking hands with Margaret Thatcher in an evening gown, is one of the most provocative fashion images of the eighties. While meeting with the Prime Minister, Katharine’s outfit not only failed to comply with generally accepted standards of conduct, but with the slogan «58% Don’t Want Pershing» openly criticised the government’s decision to support the deployment of US nuclear weapons in the UK.

In the nineties, Hamnett devoted much effort to the production of ecological clothing and withdrew from the high fashion sector, while at the beginning of the new millennium, she changed her tactics — a T–shirt series was complemented by tight fitting clothes with a print «Use a Condom. Save Africa» (2003). The goal of the project was to remind of the devastating consequences of AIDS in Africa, but this time the designer decided to do it, in her opinion, in the language the fashion industry understands — with the supermodel Naomi Campbell headlining the fashion show. Hamnett’s radical position and political activity have inspired many of her colleagues and contemporaries, while the artist’s T–shirts with slogans are the most commonly copied clothing design in the UK.

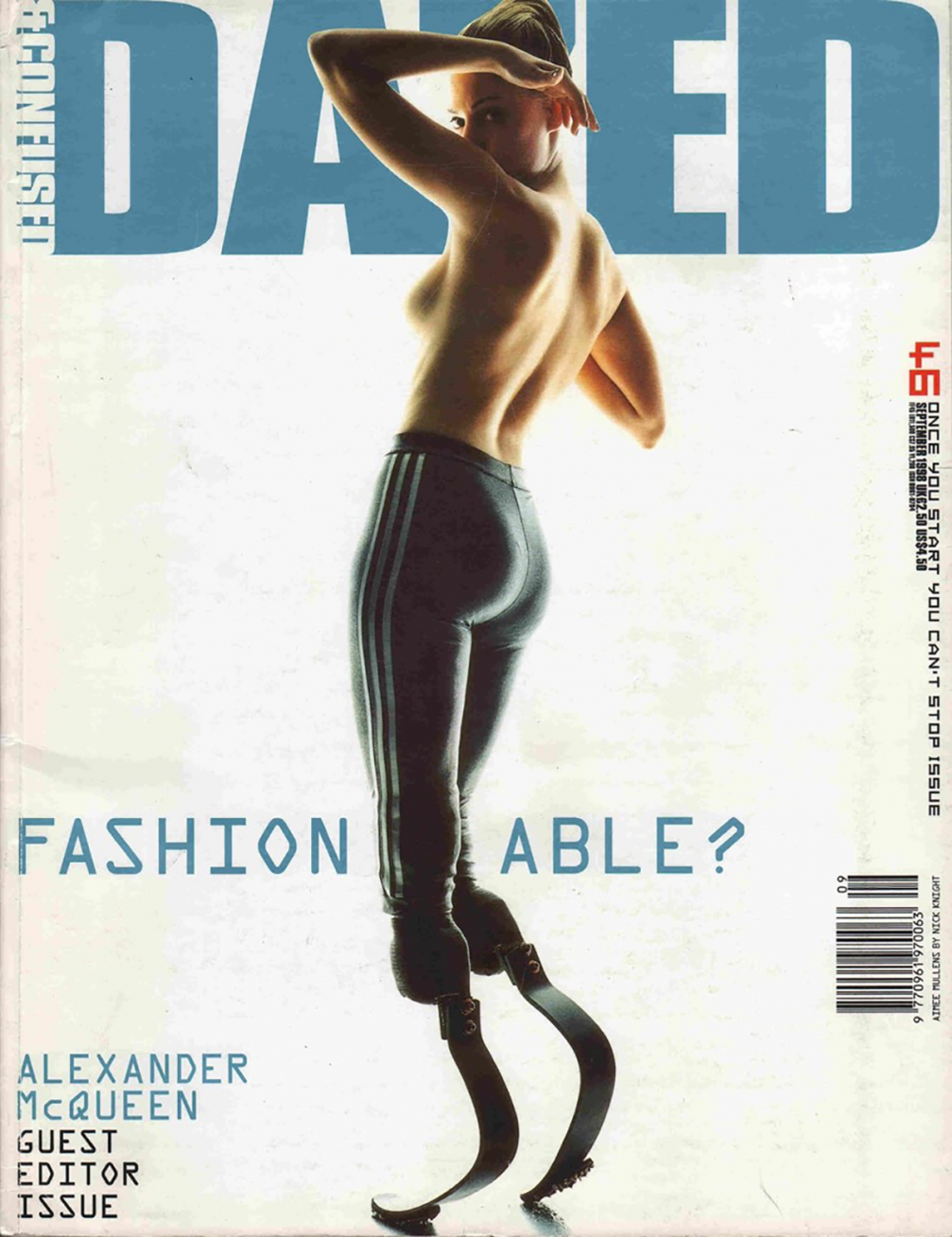

At the end of the nineties, an interesting social experiment was also performed by fashion designer Alexander McQueen when he was invited as a guest editor for the magazine «Dazed & Confused». He chose the title «Fashion–Able» for the issue and produced a photo shoot with models with disabilities. The artist justified his choice with the need to protest against the fashion industry’s efforts to idealise the human body, creating unrealistic beauty standards. For the cover, McQueen chose Aimee Mullins — an athlete with amputation of both legs. They continued their collaboration after the magazine project.

In 2014, fashion designer Gareth Pugh and photographer Nick Knight produced a series of short films «Proud to Protest», urging fashion industry representatives to react to the restrictions of LGBT rights in Russia. The presentation of the project took place within the London Fashion Week and coincided with the opening of the Olympic Games in Sochi. Prominent personalities of the fashion industry appeared in the film, such as Kate Moss, stylist Katy England, designers Henry Holland and Shayne Oliver. In total, 74 fashion professionals took part in the project, in short clips revealing their personalities by taking off black face masks — a tribute to to the Russian punk rock protest group «Pussy Riot», whose members were arrested in 2012 for a musical action «Our Lady, chase Putin out!» at the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow.

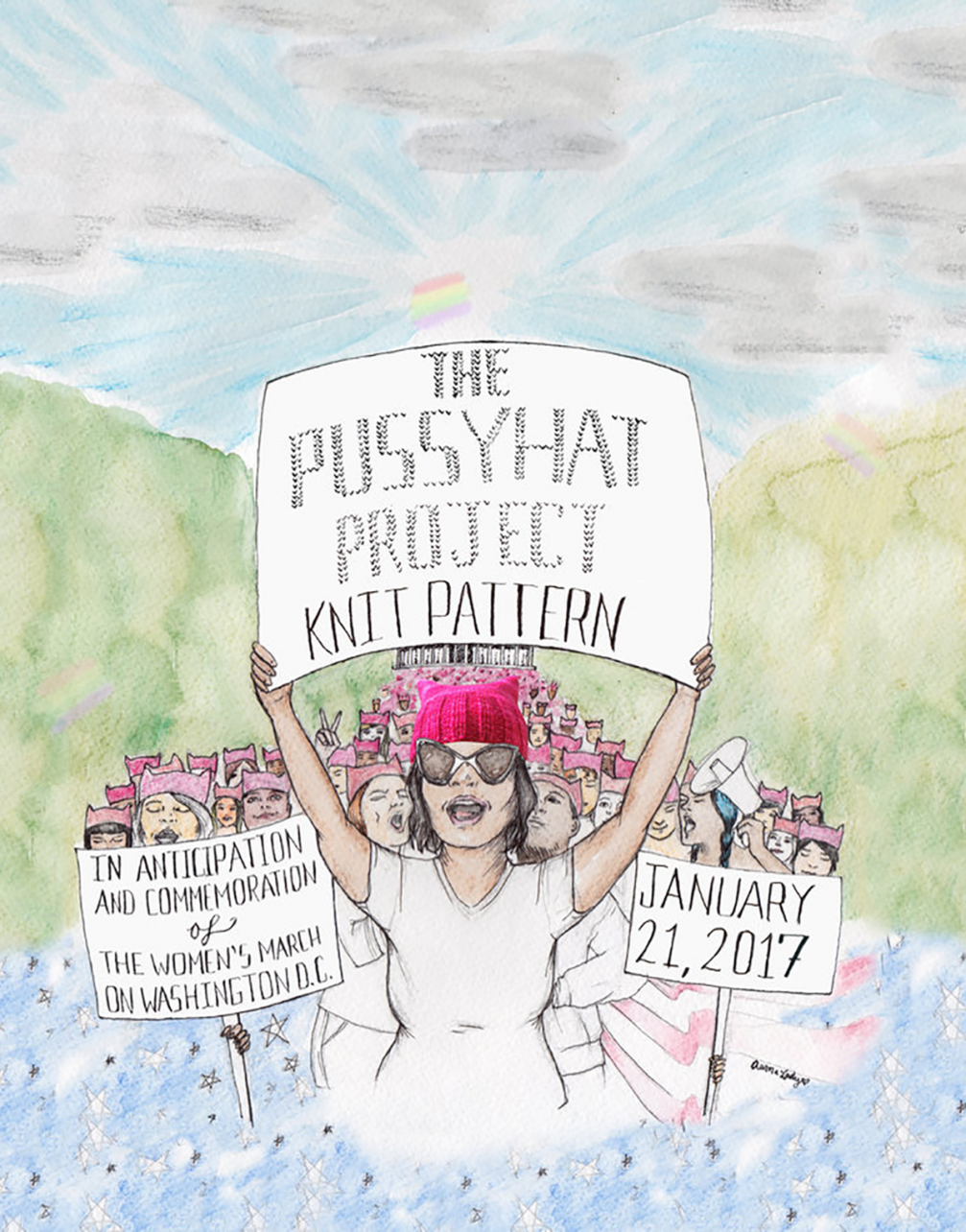

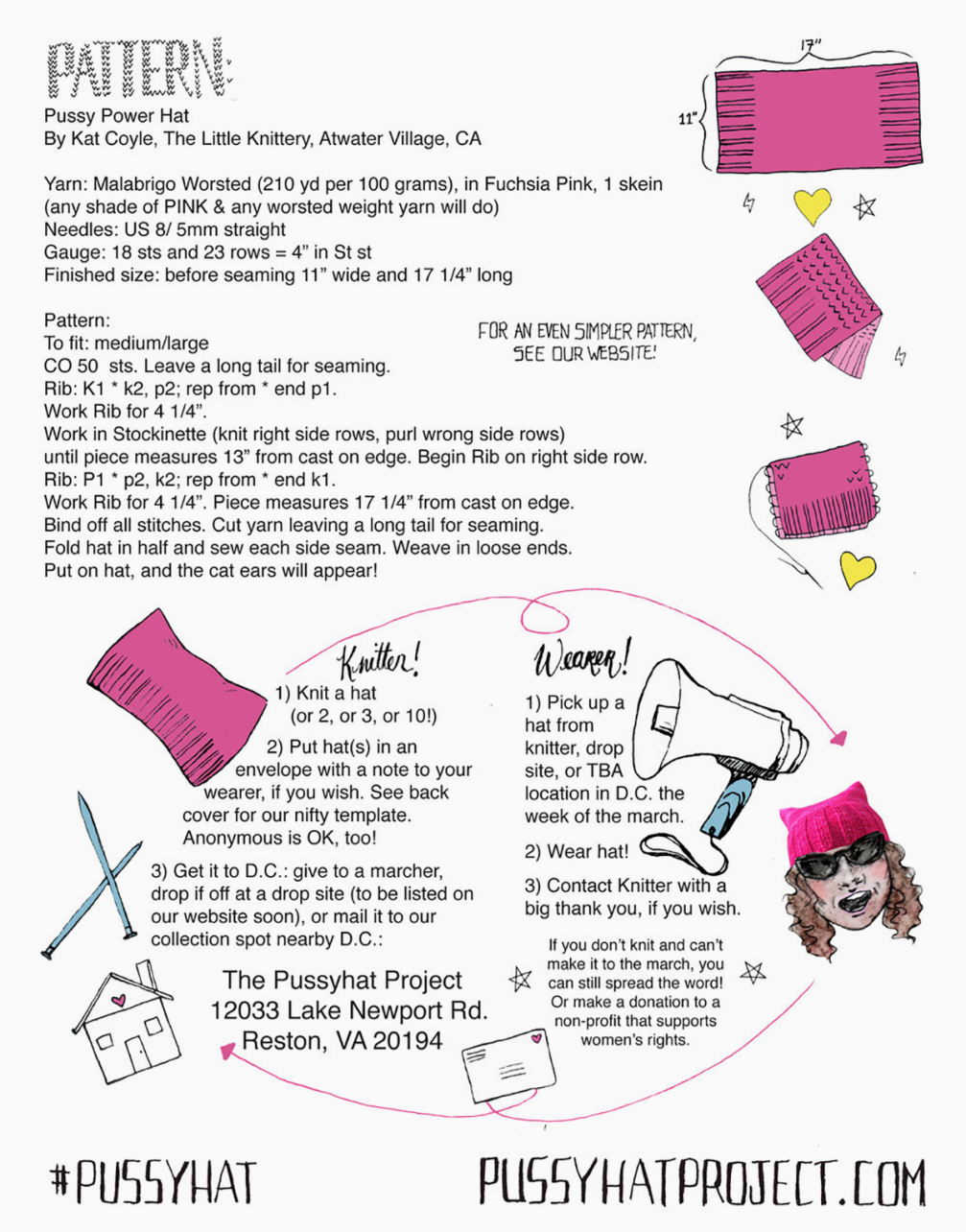

Although attractive for the media, designer manifests presented in fashion shows and magazines are not the only form of expression through fashion in protest actions. Clothing and accessories that, along with posters, attributes and decorations, help visualise the goals and ideas of the protesters, are equally important. One of the most successful recent examples is the «Pussyhat Project», which took place as part of the Women’s March in January this year. The project was initiated by screenwriter Krista Suh and architect Jayna Zweiman who campaigned to knit, sew, and crochet headwear using instructions published on their site. The pink hats with cat’s ears are an ironic paraphrase of the statements made by President Donald Trump about women and, similar to the red baseball caps of his own election campaign «Make America Great Again», became a crowd–uniting element, this time against the President. The Women’s March in Washington with a series of satellite actions elsewhere in the United States and the world has become the biggest one–day protest in US history, while the Pussyhat hats are a recognisable symbol of political activity. A month later, the hats appeared in the Milan Fashion Week at the Missoni fashion show, where they were added to each of styles of the 2017 autumn collection. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London has purchased one of the first pink hats for its collection.

Viedokļi